SA’s listeria epidemic is over. Take a look at the detectives who traced the epidemic’s source in this feature from our archives.

A mechanical hum fills the small room where James Bond is working to track down a killer. His name is printed in black letters on the side of his body.

But this James Bond isn’t the world’s most famous secret agent. It’s one of three gene-sequencing machines at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) in Johannesburg.

Working along its Matrix-inspired counterparts, Neo and Niobe, Bond is the size of an average desktop printer. But the state-of-the-art devices can determine the genetic make-up of animal and plant cells in about three days.

The trio hold the key to tracing South Africa’s deadly listeria outbreak.

Since October, Bond has been on a mission. He has been scouring DNA samples to find the fingerprints of a criminal who has killed more than 80 South Africans – listeria.

It is a common bacteria, lurking in the water, sticking to soil and hiding in the faeces of animals, such as chicken and cows. From there, it makes its way into the food we eat, from meat and dairy products to fruits and vegetables.

And this villain knows that timing is everything.

Once inside its victim, listeria can lie dormant for up to two months, infiltrating its host’s bloodstream before making its presence known through symptoms such as fever and diarrhoea.

Most healthy people who eat listeria-infected food won’t get sick but those with weaker immune systems caused by for instance HIV, diabetes or chemotherapy, are at a higher risk of infection. Pregnant women are also more susceptible to the disease, as are unborn babies, who can contract it from their mothers in the womb.

For this high-risk group, the bacteria can cause blood poisoning or bacterial meningitis, a potentially deadly inflammation of the tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord, according to United States nonprofit organisation, the Mayo Clinic.

It’s a balmy Friday morning inside the fluorescent-lit laboratories of the NICD’s Centre for Enteric Diseases. Juno Thomas’s footsteps echo in the hospital-like hallways. The centre studies viruses and affecting the intestines.

On a whiteboard on a wall next to her office, a statement in capital letters warns: JUNO THOMAS. NOT GOING ON LEAVE.

“Bacteria doesn’t take holidays, which means I couldn’t take leave in December,” she says.

She and her team have been working against the clock to track down the source of the listeria outbreak.

The NICD has reported more than 760 laboratory-confirmed listeria cases since it first declared an outbreak in October last year.

Thomas says the type of listeria making its way across South Africa has proven to be a worthy opponent: “This strain is a typical bad boy. It’s known for causing outbreaks.”

There are 10 types of listeria typically found in the environment but only one species of it, Listeria monocytogenes (the villain in this story), is almost exclusively responsible for foodborne disease, according to a 2014 study published in the Journal of Life & Medicine.

Thomas says Listeria monocytogenes has evolved to become a master of disguise. “It’s a very robust organism. Once it’s stuck on to a surface, it releases a layer of slime that sticks it down like super glue.”

This helps the bacteria to survive undetected in nooks and crannies of food-processing plants and abattoirs for years. Its slimy coat also helps it withstand freezing temperatures.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has deemed South Africa’s outbreak of the foodborne disease the biggest in history, according to a podcast interview with WHO spokesperson Christian Lindmeier by the United Nations News Centre.

But the source of the outbreak has eluded the country’s scientists so far. Thomas’s voice is urgent as she explains that her small team of about five scientists can only do so much.

Limited expertise and a short supply of expensive equipment has slowed the effort to track the source of the outbreak, as the centre battles to process the ever-increasing number of cases.

“It’s a race against time.”

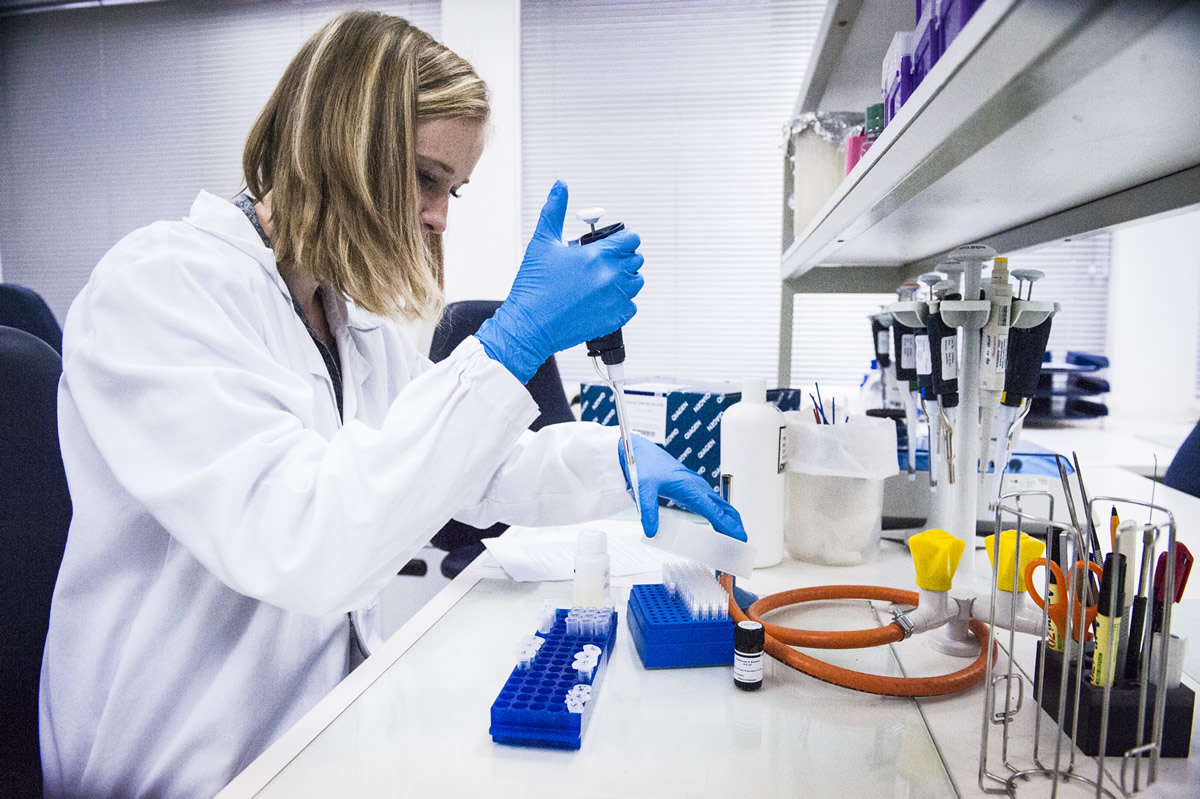

NICD medical scientist Shannon Williams hastily pulls a white lab coat over her clothes.

“The scary thing about this bacteria is that we don’t know where it’s coming from because it could be in anything,” she says, walking towards a tray of white plastic containers. Each holds a listeria sample from the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS), whose laboratories around the country are collecting suspected listeria specimens from doctors.

In December, the health department declared listeria a notifiable disease, meaning that doctors and nurses in both the private and public sectors are required to report cases to the department.

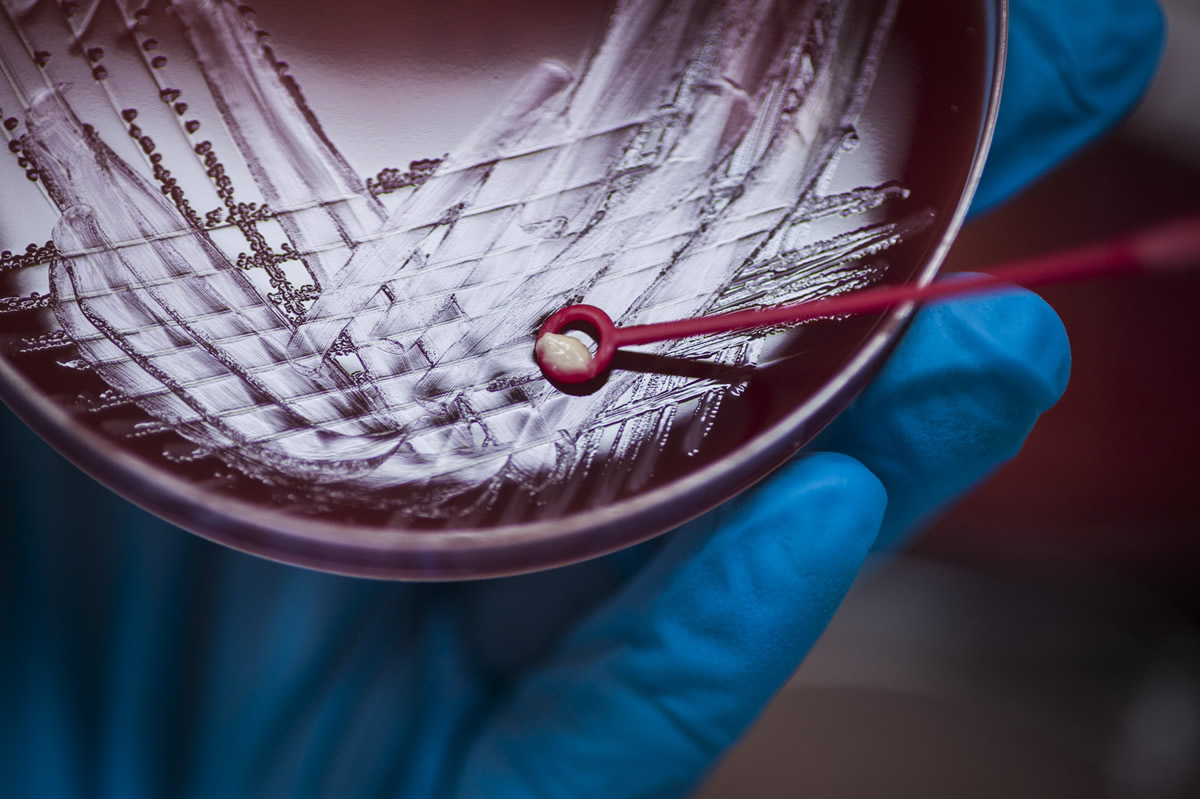

To confirm whether samples contain Listeria monocytogenes, NHLS scientists must grow, or culture, the bacteria in petri dishes filled with a vitamin-rich mixture. When the cultures reveal its presence, vials containing the bacteria are sent to the NICD. There, the process begins again and NICD scientists like Williams perform a second, confirmatory culture.

Once she and her colleagues identify the suspect, they begin breaking down the bacteria’s signature slimy outer layer to get to the genetic information inside that James Bond and company need to trace the outbreak’s source.

The trio will do this by first confirming that the listeria in samples is the outbreak strain. Next, they will attempt to match it to samples taken from food or food-processing plants. If this link can be made, it may reveal the source of the epidemic.

“Then we’ll know we have got it,” Thomas says, her eyes determined behind her cat-eye glasses.

Scientists have come close to solving the mystery. Traces of the outbreak strain were found at a Sovereign Foods abattoir outside Pretoria. The government closed the facility in December but it has since been reopened.

The company, which produces mostly poultry products, disputes the department’s finding.

It maintains the laboratory at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital, which tested samples taken from their abattoir in Hartbeespoort outside Pretoria, is not accredited to analyse food samples. A laboratory specifically accredited to test for listeria found no trace of the outbreak strain at the abattoir, according to a statement issued by the company.

Nonetheless, Sovereign Foods has tightened up its health protocols. Five new carcass washing points will be added to its abattoirs. The company will also dose carcasses with a special solution at various points in an effort to avoid cross contamination.

National guidelines, as well as those from the WHO and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, do not regulate listeria in raw poultry since the bacteria is almost always present. But both WHO and local guidelines say plants that process ready-to-eat poultry products such as polony must guarantee their equipment is listeria free.

One thing scientists know for sure is that listeria is not an elitist disease.

Nationally, listeria cases have been recorded among the rich and the poor, and this provides the NICD’s medical detectives with yet another clue – the bacterial bad boy is hiding in something that we all are likely eating, Thomas says. This rules out past and pricey serial offenders, such as soft cheeses and imported fish, which were behind other outbreaks.

That is why Thomas suspects a commonly eaten food has become highly contaminated.

Meanwhile, the health department has also called in back-up, roping in environmental health inspectors to collect clues in communities, interviewing patients about everything from what they ate, where they shopped to how they cooked in an effort to pinpoint culprit food types.

But getting people to open up about what has been on their plates isn’t always easy. Some remain deeply suspicious of inspectors and others simply can’t remember what they ate when or what brand the products might have been – information that could help scientists begin to tighten the net around the outbreak.

But increased awareness about listeria, both in the food industry and among the public, could mean the trail runs cold before Thomas, Bond and his crew ever trace their killer, she says.

“We’re hoping people will take extra caution to monitor listeria. That way the problem could sort itself out and we might never know what caused it.”

But until the NICD knows more, Bond will continue working around the clock from his corner of the institute’s gene-sequencing unit, testing samples in the hope of catching a killer in a race against time.

“It’s our only hope of finding the source.”

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.