Their life expectancy is almost as high as those who are HIV free, yet they pay much more.

Social justice organisation Section27 has been inundated with complaints about life insurance companies refusing to provide cover for people infected with HIV.

S’khumbuzo Maphumulo, an attorney with the group, said that such discrimination is unconstitutional and that access to life insurance should be based on an individual’s health status rather than on outdated exclusion policies that disregard advances in antiretroviral treatment.

“As it stands, an HIV-positive person is automatically presumed to be high risk. The fact is that many of those who are HIV-positive and on antiretroviral treatment are more likely to die from car accidents than from HIV-related complications.”

Pieter Coetzer of the Association for Savings and Investment, an organisation representing life insurance companies in South Africa, said life insurance premiums are based on assessments of a person’s risk of dying, as the policy has to pay out when a person dies.

“There are various factors that determine the cost of life cover. These include the individual’s age, education level, occupation and state of health. For example, women are generally a lower [life] insurance risk and will pay less for life cover because their life expectancy is higher than men,” Coetzer said.

However, Maphumulo said insurance companies largely overlook individual factors when dealing with HIV-infected people.

“Testing HIV-positive is used to automatically limit or deny benefits. For instance, I handled at least one case where an HIV-positive individual who, though she qualified for cover, was turned down by an insurance company on the ridiculous ground that she was underweight. She was only covered after we stepped in to assist her,” he said.

Entrenching stigma

According to Section27, making life insurance unaffordable for HIV-infected people is perpetuating the stigma around the condition.

“Everyone should be treated fairly. There is no justification for excluding people solely because they are HIV-positive. Recent studies have revealed that the life expectancy of those who adhere to antiretroviral treatment has increased significantly in South Africa. This means that there is a legal obligation on insurers to ensure that access to insurance products and related premiums are based on sound actuarial evidence that takes into account recent medical and other developments. At the moment this approach is lacking,” said Maphumulo.

The University of Cape Town released a study in April revealing that HIV-infected people on antiretroviral treatment can live almost as long as HIV-negative people. Its lead author, epidemiologist Leigh Johnson, said HIV patients who start treatment before they get sick can live about 80% as long as HIV-negative people of the same age.

“For example, in South Africa the median age of starting antiretroviral treatment is 35. So if a 35-year-old woman starts treatment when her CD4 count [a measure of the strength of the immune system] is higher than 200, she can expect to live another 33 years — this compares with an average of 39 years if she was HIV-negative. A man of the same profile can expect to live another 24 years, compared to 33 years if he was HIV-negative,” said Johnson.

The current actuarial model used by South Africa’s underwriters to calculate risk is based on relatively conservative assumptions about survival after starting antiretroviral treatment, as it was developed at a time when little was known about mortality in developing countries and such treatment programmes were reporting relatively poor rates of patient retention.

“Our latest model, which was published in 2011, is largely based on the high mortality rates observed at early treatment durations, as there is not enough long-term data available from South Africa. But mortality rates in fact reduce to very low levels at longer treatment durations,” said Johnson.

Johnson, who is a member of the Actuarial Society of South Africa’s Aids committee, helped to formulate the model.

“The current model could possibly be contributing to excessive premiums on some insurance policies for HIV-positive individuals,” he said. “We are developing a new national model, and many insurers already have their own in-house models to predict the mortality risk of HIV-positive individuals more accurately.”

Covering chronic diseases

Though life cover for people with HIV has become cheaper, Coetzer said it is often up to 50% more expensive than cover for HIV-negative people. It is, however, comparable to cover for other chronic diseases.

“In fact, in some cases cover for other chronic diseases may be more expensive. The extra premiums applicable are influenced by someone’s response to treatment and their ability to adhere to treatment, among other factors. For example, people who have had cancer, even if it may appear to be in remission, or strokes, would pay higher premiums.

“Cover for people with HIV is more expensive than for those without it, and research shows that even with good compliance with treatment, mortality for people living with HIV is still about 10% to 20% higher than for HIV-negative people,” he said.

Johnson said another factor determining higher insurance premiums for people with chronic diseases is administration costs. “One of the conditions of cover, for many HIV-positive insurance policies, is that the policyholder has to stay on treatment, which means that the insurers have to put measures in place to monitor them. The extra administration costs could potentially be part of the reason for high premiums on some HIV-positive life insurance policies.”

Altrisk, a company that specialises in life cover for HIV-infected people, said each case should be judged on its own merits. Altrisk managing director Michael Blain said that “there is no average when it comes to HIV — no two clients are the same. One may control their condition and treatment very well, be disciplined in medical care and respond well to antiretroviral treatment. The second applicant may not manage their condition as effectively and have significant associated risk diseases.”

Blain said the company had only dealt with two Aids-related deaths in over a decade. “Today, we are seeing millions of HIV-positive people living longer lives than scientists ever imagined possible back in the 1980s. Experience has shown us that HIV is a chronic illness, not a life threatening disease.”

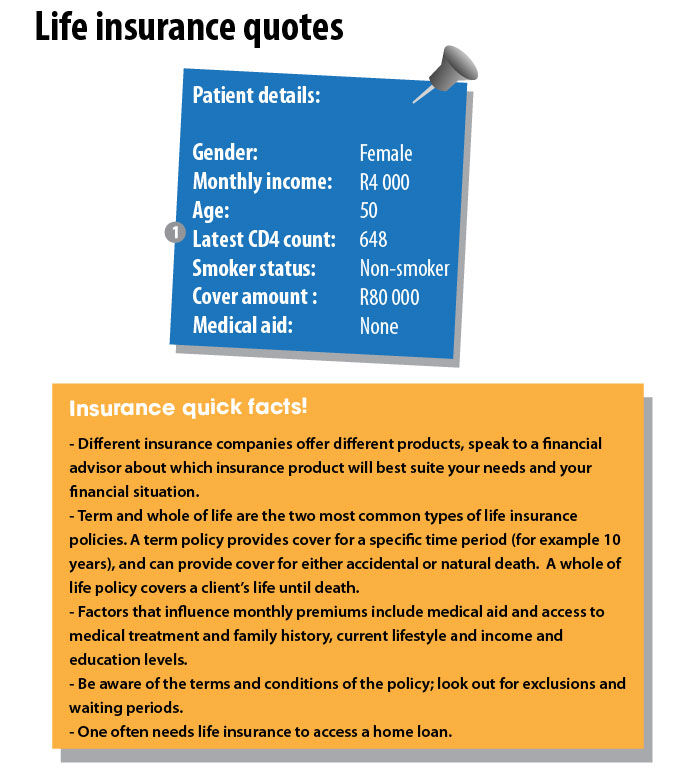

?

?

?

?

?

?

Patient compliance with treatment is vital

South Africa was the first country to make life insurance available to HIV-infected people, in 2001. But 12 years later, those with HIV still face the reality of paying higher premiums to the limited number of insurance companies willing to cover them because HIV is still deemed uninsurable by some.

Pieter Coetzer, of the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa, which represents the life insurance industry, said pricing is based on evidence of the effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in the long run. “Local studies on active antiretroviral therapy outcomes have only started appearing recently, but follow-ups generally do not exceed a period of two years. We are still awaiting evidence on long-term outcomes.”

He said providing cover for HIV-infected people is especially problematic because the efficacy of antiretrovirals relies heavily on treatment adherence, which requires the insurance companies to conduct constant follow-ups. “Compliance depends on access to drugs, side-effect tolerance and viral resistance. It is possible to underwrite risk cover only once on the date of application, as with normal insurance products, however this will lead to a higher premium. HIV products with continuous monitoring of treatment compliance ensure more affordable premiums,” said Coetzer.

HIV-positive people can access more affordable life insurance if they can show compliance with the treatment prescribed to them. But, in order to prove that, they have to submit regular blood-test results to insurers detailing their viral loads (how much HIV is in the blood) and CD4 counts (a measurement of the strength of the immune system) — viral loads and CD 4 counts indicate whether the treatment is working; the lower the viral load and the higher the CD4 count, the better the treatment is working.

Coetzer said that “it is foreseeable that people with HIV may be accepted for normal insurance products within the short-term future” due to the positive results of antiretroviral treatment found by recent studies.

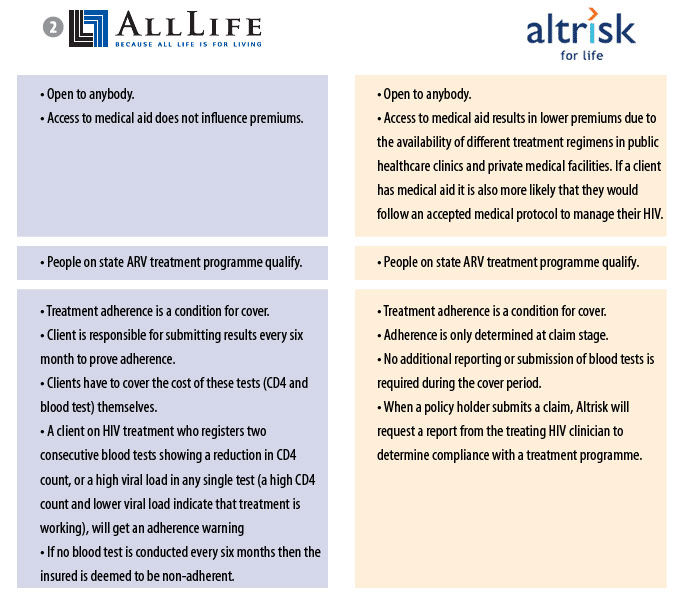

In cases where special measures have to be taken, for example monitoring of compliance, it may be cheaper for smaller companies to focus on a niche market, he said. For example, Altrisk and AllLife are two of the country’s insurance companies specialising in life cover for people with HIV. “This is, however, heavily dependent on the condition at stake and the underwriting processes required to make the product sustainable.”

Insurance companies are legally obliged to make their products financially viable. According to the Long-term Insurance Act, premiums must be calculated to fit the expected risk of the person insured. The Act states that the assumed risk must be based on an individual’s profile.

Ina Skosana was a health reporter at Bhekisisa.