HIV diplomacy can be used to help the country become a better, more influential global citizen.

COMMENT

In 2006 the foreign ministers of Brazil, France, Indonesia, Norway, Senegal, South Africa and Thailand launched the global health and foreign policy initiative.

In March 2007 they issued the Oslo ministerial declaration, stating that “health is the most important, yet still broadly neglected, long-term foreign policy issue of our time”.

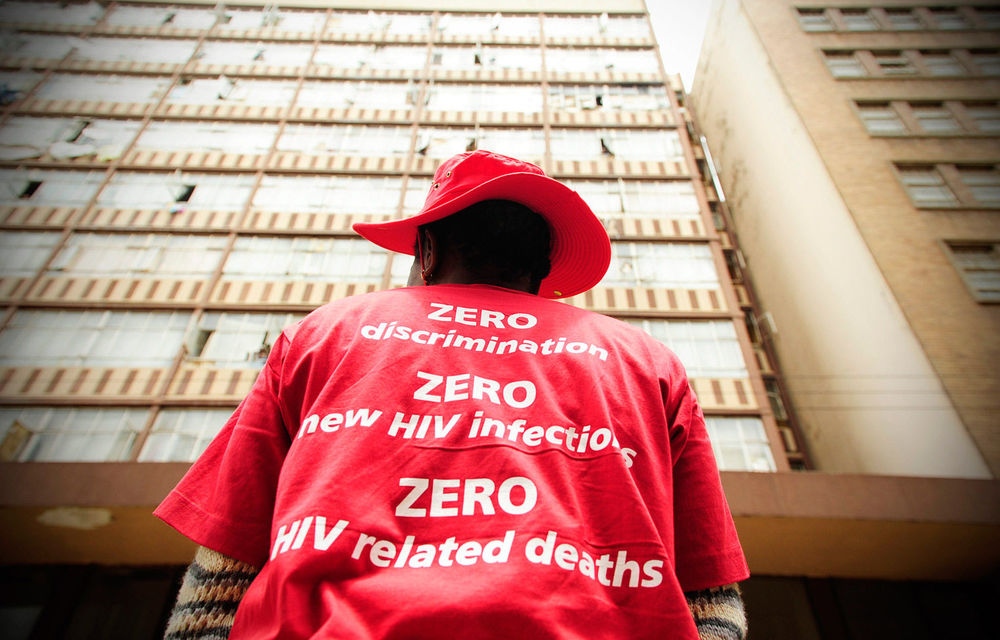

South Africa can build foreign policy influence around global health in general and Aids specifically to regain some of the influence and credibility that we lost due to our diplomatic inconsistencies and the Thabo Mbeki administration’s Aids denialism.

An emerging Aids diplomacy could use HIV to foster relations and give South Africa a stronger foreign policy presence.

The post-Mbeki foreign policy environment is muddy, and a focused conversation in the policy community would be a worthwhile consequence of the development of fresh foreign policy thinking and practice.

It is important that such a conversation should include members of South Africa’s Aids civil society.

South Africa set an important Aids diplomatic precedent in the late 1990s when it defeated the 30 big pharmaceutical companies that took it to court to fight the health department’s importation of generic HIV drugs while the patent rights of brand medicines had not yet expired.

In the same way, the experience of the HIV advocacy group, the Treatment Action Campaign, and its international alliance partners, has provided insight into the kind of nongovernmental and transnational diplomacy that it practised so successfully.

In addition to the development of an inclusive definition of South African Aids diplomacy, HIV could help heal the rifts that still exist due to the antagonistic positions of the Mbeki administration and Aids civil society.

The first area of attention for Aids diplomacy is global trade, as the link between trade and health highlights the new prominence of health within foreign policy.

Both Brazil and South Africa have strong records of achieving transformation in existing multilateral trade rules regarding pharmaceuticals.

Also, transnational issue networks – such as HIV organisations, activist states and HIV advocates – have achieved remarkable progress in negotiating lower prices for anti-retroviral drugs.

South Africa should advance its trade agenda with a specific focus on the facilitation of technology transfer and the sharing of research, north-south as well as south-south.

The second agenda item pertains to South Africa’s status as an emerging middle power.

Because this is a status that the country wishes to build on, it should explore closer ties with Brazil as well as with other emerging middle powers, and it should seek to align common goals for united global health diplomacy that can be used to improve foreign relations.

Issues that could be explored at the level of Aids diplomacy multilateralism in the case of member organisations such as the United Nations or the Southern African Development Community (SADC) include the transformation of the existing architecture of global health governance.

Concerted public diplomacy and advocacy within the World Health Assembly, the body that governs the World Health Organisation, would demonstrate middle powers’ ability to set the agenda instead of simply affirming the list of priorities that emanates from Geneva and New York.

Such an amended agenda should emphasise the strengthening of health systems in middle and low-income states and highlight the need for sustainable funding of health initiatives in poor countries.

In this way, South Africa could give voice to those who are normally excluded from multilateral forums, including the elderly, women, ?children and people living with HIV.

South Africa could set up an institution focusing on health issues within SADC. A pan-African organisation that is devoted to health issues might do better than subsuming health as one of many policy areas at the SADC secretariat.

South Africa could also form a consortium of southern states via Brics (Brazil, Russia, India and China and South Africa) or Ibsa (India, Brazil and South Africa) to work for this common purpose.

South Africa should also strengthen “catalytic” diplomacy, which refers to multiple interactions and common purpose across state and nonstate actors and activities.

Transnational issue networks play an increasingly critical role as global norm entrepreneurs, and this should be cultivated. Political momentum can be built by linking HIV activist networks with movements that seek equity, justice and fairness.

Aids diplomacy could also be beneficial in training and retaining health personnel, and addressing the causes of the unequal global distribution of doctors and (especially) nurses.

This is a critical area for the management of infectious diseases and, at the moment, the global south loses thousands of its medical personnel to the global north.

Any initiative to address this should reflect on both the push and the pull factors – facile condemnation of rich countries’ recruitment practices should not blind governments in the global south to those determinants of migration that are within their control.

South Africa might start such an initiative by pushing for progress on developing more advanced international codes of conduct on the recruitment of health personnel.

Finally, South Africa can take the lead in training health diplomats.

The Oslo ministerial declaration has opened a window of opportunity to use health to affirm the status quo of global health governance, and also to reform the health architecture and to consider the kind of global order that might be possible.

Similarly, Aids diplomacy can be a project of transformation and emancipation for South Africa, which is in need of a refocused and rejuvenated foreign policy.

Aids can be used as an issue to consolidate the country’s young democracy, and it can work with trans-national issue networks to strengthen middle power multilateralism.

If South Africa can get this right, it has the real potential to turn dread into capital, rather than to default to positions of impotence and blaming outsiders.

Pieter Fourie is an associate professor in the political science department at Stellenbosch University.