Rwanda, too, has succeeded in doing what this country has only been talking about for 18 years.

In 1988, less than half of Brazil’s population had health coverage, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). But by 2008, it estimated that 75% were covered.

By the early 2000s, nearly a decade ahead of schedule, Thailand had beaten or was on track to meet all of its millennium development goals, according to the United Nations Development Programme. The millennium development goals are eight international targets supported by United Nations member states to be achieved by 2015.

Rwanda government figures show that in less than two decades the country’s life expectancy improved from 30 to 55 years.

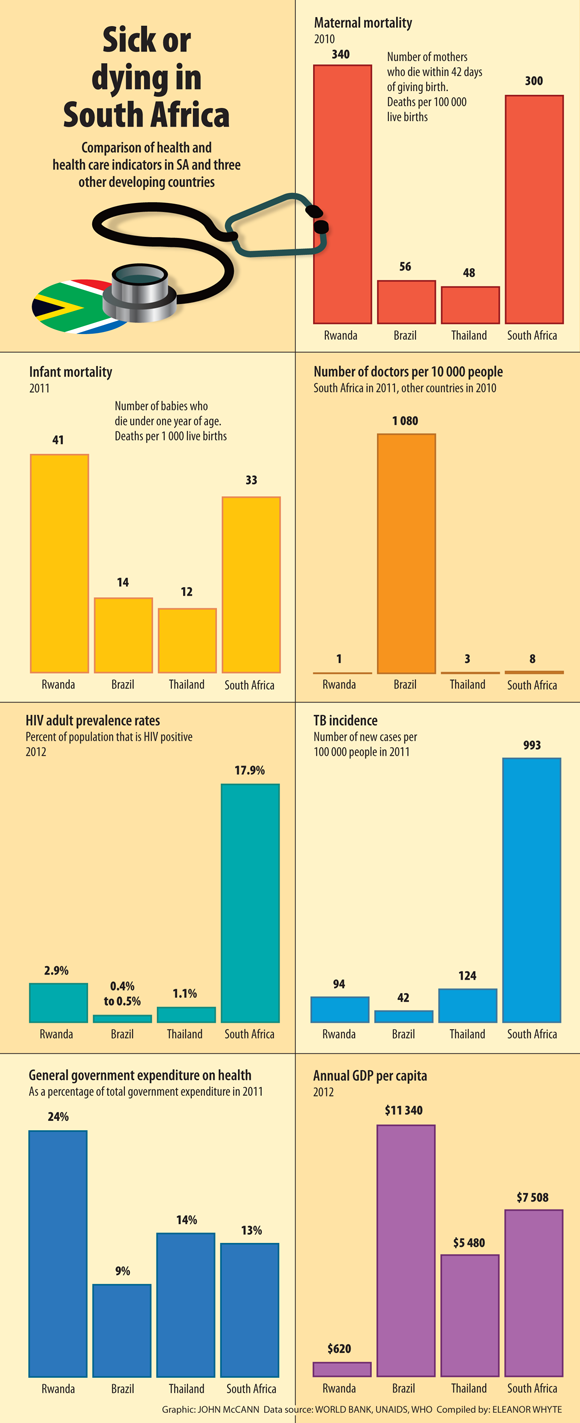

Jump to South Africa. Despite paying significantly more on health than other low- and middle-income countries, some of the country’s health indicators actually deteriorated until recently. South Africa’s maternal mortality nearly doubled between 1990 and 2007, according to the country’s millennium development goals 2013 country report.

Things have been improving this decade but, as of 2013, 269 women died for 100 000 live births, according to the report, far above the millennium development goals of 38 deaths for 100 000 live births. The WHO groups South Africa with 40 other countries, including Haiti, Liberia and Niger, as having the worst maternal mortality rates in the world.

Primary healthcare focus

As outlined in the health department’s green paper on National Health Insurance (NHI), the government aims to improve health by strengthening primary healthcare and equalising public and private services. The underlying goals are fairly simple: to ensure that everyone – regardless of income, location or health burden – can access adequate health services; to focus on disease prevention and health promotion by expanding and strengthening primary care; and to ensure that accessing these services doesn’t place an unnecessary financial burden on patients.

South Africa’s NHI is often compared with reforms undertaken by Brazil, Thailand and Rwanda. Their successes act as benchmarks against which the country may be measured.

In 1988, Brazil’s reformed Constitution declared that health is a human right of every citizen and a duty of the state. As such, the Sistema Único de Saúde (Unified Health System) was born. At its core is the family health programme, made up of teams that include a physician, a dentist, a nurse and a community care worker, who are attached to a clinic but also provide care in communities. They focus on health promotion and preventative care.

Brazil’s made progress

Brazil has abolished health fees and subsidised the majority of its medicine.

According to the country’s ministry of health, by the end of 2007, 80% of Brazil’s HIV-positive population eligible for treatment had access to antiretrovirals, compared with just over 50% in South Africa today.

Brazil, however, has lower HIV rates. Statistics South Africa estimates that, as of May 2013, 15.9% of South Africans aged 15 to 49 were HIV positive. But, as of 2012, only 0.3% of Brazilians in the same age category were infected, according to the most recent United Nations Programme on HIV and Aids statistics.

According to the WHO, Brazil’s infant mortality decreased from 46 for 1 000 live births in 1990 to 18 for 1 000 live births in 2008. The organisation also notes that life expectancy rose from 67 years in 1990 to about 73 years in 2008.

The WHO credits Brazil’s successes in part to decentralisation. The country’s states and municipal governments control health management and financing. According to the WHO, states are required to allocate 12% of their budgets to health; municipalities are required to allocate 15%. The federal government also finances the programme from taxes.

Brazil still hosts a private health sector: those who buy private health insurance get a tax rebate but they contribute to the country’s Unified Health System through income tax.

Thailand’s health reforms

The good health at low cost project, conducted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, notes that massive health reforms were instituted in Thailand when, beginning in the 1970s, a series of charismatic and influential health ministers were appointed who focused on public health and equity.

Like Brazil, Thailand’s health reforms were built on a decentralised system. By requiring all new medical graduates to serve in public health, the country’s district health systems were adequately staffed, with nurses and community workers forming the backbone of the health system. A new cadre of nurses was also introduced to meet increased demands.

The good health at low cost project notes that, by the 1990s, all Thai citizens had free access to antenatal care, family planning, immunisation and skilled birth attendance. The elderly, children and poor are exempt from user fees. For everyone, out-of-pocket payments have dramatically reduced.

Besides meeting the majority of its millennium development goals in the 2000s, well before the 2015 deadline, the country has set its own goals, referred to as the millennium development goals plus, which aim to reduce poverty to below 4%, achieve universal education and reduce maternal and infant mortality.

Rwanda had a bumpy start

In Rwanda, health reforms envisioned in the 1980s but marred by the country’s genocide were reinvigorated with the return to peace.

Like Brazil and Thailand, Rwanda focused on decentralising health management to local government.

According to a report by Rwanda’s ministry of health, published by the Global Economy and Development Programme at the United States think-tank the Brookings Institution, the country uses community dispensaries, health posts, clinics and district hospitals as the core of its system, with referral hospitals caring for the most severe cases.

About 45 000 community healthcare workers support people living with HIV and provide primary care services in communities. The report also notes that hospitals, clinics and community healthcare workers who follow up with patients and show improvements in primary healthcare are given financial rewards.

Brazil and Thailand attempted to limit or entirely remove user fees, but the Brooking report notes that Rwanda implemented them in 1994 to supplement depleted health budgets after the war, a move that catastrophically affected service utilisation and results deteriorated.

However, things have changed. The report notes that 91% of the country uses community-based social insurance schemes to cover curative services, in which members pay premiums of about $6 a person a year plus a 10% service fee at clinics and hospitals.

This system has halved annual out-of-pocket health spending; in 2010, the government began subsidising premiums and co-payments for those living in poverty. Preventative care, such as HIV testing and tuberculosis screening, is free.

By 2011, Rwanda had placed more than 80% of HIV-infected people needing antiretrovirals on therapy and reduced the number of malaria deaths from 2?486 in 2006 to 380 in 2011, according to the WHO.

Different burdens but similar focus

The three countries have different burdens of disease, economies and health models, but the reforms they have undertaken have striking similarities: community-based services, decentralised health financing and management at a local level, and a focus on maternal and child health. The reforms were also supported by strong political will.

William Hsiao, professor of economics at the Harvard School of Public Health, warns that, although South Africans can learn from other countries’ attempts at expanding care, “South Africa faces a very unique problem, which very few other countries had. Namely, you have a dual system of healthcare financing and delivery: one for the more affluent people, [which is] a well-established private insurance sector, like your medical schemes and private hospitals and clinics, for roughly … 20% of your people. And the other 80% rely on public health services … I would say 30% to 40% of South Africans do not even have primary care.”

According to the health department’s NHI green paper, per capita annual expenditure for those with medical aids is estimated at R11 150 a year, compared with R2 766 a person a year in the public sector.

Hsiao has been studying the functioning and reforms of health systems around the world for decades and has been involved in discussions with South African policymakers.

He notes: “The disparity is one of the greatest we observe around the world … When you’re trying to make them converge, it’s much harder.”

Can’t ignore hospitals

Focusing on primary healthcare, as is envisioned through NHI, “would focus on the 40% or more of the people who are in the greatest need”, Hsiao says. “If we’re talking about social equity and justice, then the priority should be focused on establishing effective primary care systems.”

Although primary healthcare will be the key tenet in South Africa’s attempts at universal coverage, Hsiao warns: “You cannot ignore hospitals. Those systems have to be much better organised and managed. The whole structure of these hospitals has to be reformed.

“Brazil reformed its primary healthcare but did not reform its hospitals and now … people are unhappy because, when they are seriously ill, they cannot get the right kind of services, and the services are very unequal.”

South Africa’s system is currently hospital centric. Di McIntyre, a professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Cape Town, has estimated that over 80% of all health resources go to hospitals.

The green paper notes that, within a decade, private hospital costs increased by 121%.

Corruption

Disparity between the public and private sector isn’t the only stumbling block for the implementation of the NHI. Hsiao says that corruption within the health sector – and particularly at the provincial level – poses a significant threat to the NHI.

“With the money the central government allocate[s] to provinces, and provinces to districts, you have very little assurance that the money will be used effectively and efficiently,” he says. “That’s the biggest barrier in South Africa.”

Hsiao notes that Thailand relied on districts to pay for health services “but it did not have the level of corruption at local level [as South Africa does]”.

Countries such as Taiwan and Canada rely on central government purchasing and countries that have achieved universal coverage quickly, such as Thailand and China, also had economies that were booming and enacted other reforms like increasing literacy rates and introducing poverty reduction programmes.

According to the World Bank, South Africa saw a steady increase in gross domestic product (GDP) annually of about 5% throughout the early 2000s but this has slowed down. The bank notes that the country’s GDP increased by only 2.5% in 2012 – less than inflation of 5.4%.

A question on everyone’s lips is how much the NHI will cost and how it will be paid for. According to the green paper, the government’s NHI white paper – meant in part to address these issues – was to be published for public comment in August 2011 but is still behind closed doors.

A treasury document considering financing options may come out by the end of the year.

Despite significant obstacles, Hsiao says that South Africa has the know-how, expertise and knowledge to reform its healthcare system.

“South Africa has to do it. I served on a commission in 1995-1996 and we designed something for [universal coverage] for South Africa but [the country] never took the first step. Eighteen years later, I would say the condition [of the system] has vastly deteriorated and, with that experience, South Africa has to do it.

“I think you now have [the] political commitment to do it. The country has a minister who’s willing to lead, and who knows how to lead in a very complex political situation.

“If you want to go to the moon, you have to take the first step.”

________________________________________________________________________________________

Those key to the service must be cared for

“I can give you 10 countries as good models and they have one thing in common,” says William Hsiao, professor of economics at the Harvard School of Public Health, reflecting on decades of research into comparative health systems. “They use community health workers.”

The health department’s National Health Insurance (NHI) green paper envisions community health workers as the backbone of its primary healthcare plans.

The People’s Health Movement of South Africa, the Community Care Workers’ Forum and the Wellness Foundation note that community health workers have been effective in expanding access to care in countries such as Thailand and Rwanda.

But they criticise the way that health workers are trained, treated and paid in South Africa. The average community health worker earns R800 to R2 000 a month, is not given effective protective equipment (they say some use plastic bags for want of gloves), is on an annual, unstable contract and is offered little or no training.

Janet Stanford, chief executive of the Knysna Hospice, says these conditions affect staff retention.

The hospice employs 30 community health workers with money from the provincial health department. They provide health education and basic healthcare services.

Stanford says that, although community health workers used to be employed full-time, they are now part-time, as directed by the provincial health department.

Since then, “recruitment and retention has been more difficult”.

“Currently, a cleaner at a provincial hospital or clinic has way better remuneration than them [community health workers], who have dedication, commitment and … are exposed to quite hazardous situations.”

For working four-and-a-half hours a day at the hospice, a community health worker gets R1 330 a month.

The health movement and its partners also say that many more community health workers need to be hired for the country to see similar gains to those made in Rwanda and Thailand.

In those countries, the ratio of community health workers to households is between 1:10 and 1:20. In South Africa, the current ratio is 1:270.

Research by Eleanor Whyle

Mara Kardas-Nelson was an OSF fellow at the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism.