Personal beliefs sometimes collide with healthcare providers’ professional responsibilities.

“The last dream I had was a few nights ago. I am back home in Hlabisa and my boyfriend hands me a baby,” says Gugu Ngubeni*. “It looks like a normal child, except that it has no eyes.”

Ngubeni takes a deep, shaky breath. “I think it’s because they showed me the baby. Maybe if I hadn’t seen it I would not be having these kinds of dreams.”

It has been months since Ngubeni went to the Lower Umfolozi Regional War Memorial Hospital in the KwaZulu-Natal town of Empangeni to get an abortion. But what was meant to be a simple procedure turned out to be a nightmare that she would relive for months to come.

On May 27 Ngubeni’s boyfriend dropped her off in front of the hospital for her appointment. She was three months pregnant. The 26-year-old says she was already nervous about the procedure, but when the nurses on duty told her that they were going to show her the foetus once it had been removed, an immense fear washed over her.

“I don’t know why they would do that; if I wanted to see it I would have asked. But they [nurses] said they would show me by force.”

And they did. Ngubeni remembers seeing how the separate feet, head and two hands of her semi-developed baby were emptied from the tube that was used to extract it from her uterus. “I was traumatised,” she says.

Personal beliefs

This, according to Jane Harries, the director of the Women’s Health Research Unit at the University of Cape Town, “is definitely not what they [nurses] should have been doing”.

Ngubeni says the nurses also shouted at her during the course of the procedure, accusing her of sleeping with older men. “It was painful, the nurses were heartless. They didn’t even give me something for the pain,” she recalls. “They were supposed to help me, not shout at me.”

Research conducted by Harries shows that there is a lot of opposition to abortions and that sometimes health professionals do not separate their “personal beliefs from the service that they should be providing”.

“They can also reprimand the women and not take a very professional stance towards these women.”

National health spokesperson Joe Maila admits there are “instances where patients are not treated as expected. The issue of staff attitude forms part of the core standards that must be adhered to at all times. However, I must point out that there are [also] selfless health workers who are doing a great job.”

Personal politics

Rebecca Hodes, a medical historian at the University of Cape Town who has conducted extensive research into the history of abortion in South Africa, says that women seeking abortions at private health facilities also report abuse.

“The personal politics of many healthcare workers are at odds with the legal commitment and the public health imperative to provide comprehensive reproductive healthcare, including abortion.

“My research on the provision of abortion in the public health sector has found that the denial of analgesics [pain medication] to abortion patients may sometimes be used to punish women for having abortions, and to discourage them from seeking ‘repeat’ abortions,” she says.

The national health department has, on various occasions, raised concerns about the number of women having repeat abortions. At the launch of the government’s new contraceptive policy in February this year, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi said: “We know that many women, especially young girls and women use termination of pregnancy as a contraceptive method.”

But Harries says that more evidence based research is needed to find out the extent of repeat abortions. “All of the research that we’ve undertaken does not necessarily suggest or indicate that women are coming for repeat abortions or using it as a form of contraception. If they are, then we need to look to our contraceptive services to see where we are failing women.”

Socioeconomic reasons

According to Hodes the most common reason why women like Ngubeni seek abortions is socioeconomic, where the woman doesn’t have the means to care for a child.

Ngubeni is unemployed and her four-year-old child is being taken of by her mother. Her boyfriend, who only has a part-time job, also has a four-year-old from a previous relationship.

“We should have thought about that before we had sex without a condom. We were both at fault. I know we made a mistake and abortion is not a solution, but I can’t bring another child into the world that I cannot take care of,” she says.

“It wasn’t an easy decision to make but I didn’t have a choice.”

Harries says that women in rural areas often lack access to facilities that provide abortions, but government has “really made an effort to work with private sector and nongovernmental organisations to support abortion services”.

Activists say that fewer than half of the 460 government health facilities designated to provide termination of pregnancy are actually providing the service.

Training and support

In order for women to fully access safe and legal abortions, Hodes says that health facilities across the public sector need to be better resourced and abortion providers need adequate training and support.

For Ngubeni, having an abortion is a decision that will haunt her for a long time to come.

“I definitely regret doing it,” she says. “It hurts. Every time I see a child on TV, I wonder what my baby would have looked like.”

* Not her real name

Obstacles persist for safe, legal termination

With the collapse of apartheid and the advent of democracy in the early 1990s, “sweeping changes to South African laws” were made, explains Rebecca Hodes, a medical historian at the University of Cape Town.

“In 1996, the Abortion and Sterilisation Act of 1974, which barred legal access to abortion except within narrow structures, was replaced by the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act.”

This Act, which came into effect in 1997, gives women the right to an abortion on request during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, the right to an abortion at 13-20 weeks if the health of the women or foetus is at risk or if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, and after 20 weeks if the health of the woman or foetus is at stake.

Yet Hodes, who has studied the history of abortion in South Africa, says research has shown “consistently that, while laws and policies regarding women’s health have changed in post-apartheid South Africa, the practice of healthcare workers and the experiences of patients hold many similarities with apartheid health practices”.

Illegal abortions

“South Africa’s culture of illegal abortion is partly the legacy of apartheid reproductive policies, in which access to legal abortion was severely proscribed,” she says. “The result was that many thousands of women resorted to illegal abortion to end their unwanted pregnancies. Despite changes in the law, this remains the reality today.”

The director of the Women’s Health Research Unit at the University of Cape Town, Jane Harries, says that women who are ill-treated when seeking health services in the public sector have the right to lodge formal complaints.

“I think people should be doing that, because [patients] are badly treated but people don’t [complain]. I think they’re sometimes just so relieved to be helped that they never do [complain],” she says.

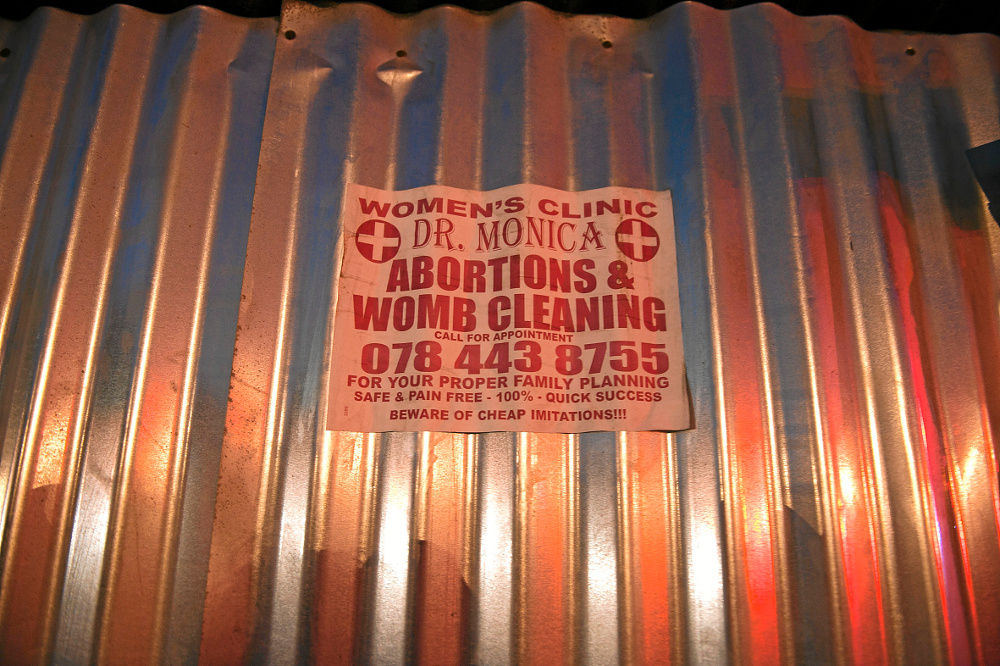

Women who receive suboptimal health services when seeking abortions are often afraid of being victimised if they speak out. Hodes says patients in this situation have little recourse and often turn to “illegal abortion through ‘lamppost’ providers”, referring to unlicensed abortion providers who advertise their services on the street or lampposts across the country.

An unsafe or illegal abortion, according to the World Health Organisation, is a termination of pregnancy conducted in “unhygienic conditions, or by a health practitioner outside official or adequate health facilities”.

Dangers of unsafe abortions

The dangers of unsafe abortions include the lack of “immediate intervention if severe bleeding or other emergency develops during the procedure” and “failure to provide post-abortion check-up and care”.

The World Health Organisation estimates that one in five pregnancies globally end in induced abortion, and 21.6-million of the 43.8-million abortions that occurred in 2008 were unsafe.

Almost all of unsafe abortions happen in developing countries; more unsafe abortions are conducted in these countries than safe abortions.

Research shows that prior to the introduction of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act, complications from unsafe abortions were a leading cause of maternal deaths in South Africa.

According to the United States National Institutes of Health, “unsafe abortion is a significant contributor to worldwide maternal mortality; however, abortion law and policy liberalisation could lead to drops in unsafe abortion and related deaths”.

Septic abortions

The report found that the same is true for South Africa, where estimates for unsafe abortions between 1975 and 1996 ranged from 120 000 to 250 000 per year. The unavailability of legal abortion during those years, says Hodes, led to a large number of women seeking “abortion in the informal health sector, resulting in high levels of mortality and morbidity from septic abortions”.

According to the National Institutes of Health, “the abortion law of 1996 was the first step towards significant reductions in unsafe abortions. In 1994, complications from unsafe abortion led to 32.69 deaths per 1 000 abortions. By 1998, only 0.80 deaths per 1 000 were reported.”

The report further states that there was a 91% decrease in deaths related to unsafe abortions between 1998 and 2001 in South Africa.

But national health spokesperson Joe Maila says the department does not have an estimate of the number of unsafe abortions provided in South Africa.

“However we believe that the number could be very high, given the seriousness of the adverts we see all over in the country promising ‘safe, painless and quick’ abortions, and the number of women who come to our facilities with pregnancy-related complications as a result of unsafe backstreet abortions,” he says.

Maternal mortality

But the abortion laws did little to improve the overall number of South African women who die during pregnancy, childbirth or shortly thereafter. Even the reported uptake of safe, legal abortions, with more than 90 000 abortions performed in government clinics and hospitals between April 2013 and March 2014 – almost 20 000 more than the previous year – has not translated into a decrease in maternal mortality.

The United Nations estimates that maternal deaths in South Africa have increased from 250 deaths per 100 000 live births in 1990 to a peak of 360 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2005.

The latest government estimates of 269 deaths per 100 000 live births is not only higher than the 1990 figures, it is also more than six times the target South Africa is supposed to achieve by 2015.

“We are not able to provide the exact percentage [of maternal deaths due to unsafe abortions] at this stage, but I can confirm that indeed, unsafe backstreet abortions contribute to maternal mortality, as some women die of septic miscarriage as a direct result of unsafe abortion,” says Maila.

Obstacles remain

Despite legislation legalising abortion, obstacles to accessing safe legal abortions remain.

“The barriers include a shortage of trained legal abortion providers – particularly second trimester abortion providers. Those are abortions provided when the pregnancy is greater than 12 weeks, so between 12-20 weeks, which can only be performed by a doctor,” says Harries.

The stigma of abortion is as much an obstacle to women accessing the services as it is to the doctors and nurses who provide the services. “Many healthcare providers that are providing the services don’t always feel fully supported by the people they work with. They are ostracised, isolated and stigmatised themselves because they are providing the service.”

Harries says that health professionals who are working under these conditions often experience burnout and frustration.

“The women [who seek abortions] on the one hand are on the receiving end of not always getting the most optimal treatment, but equally some of those healthcare providers that have opted to provide those services aren’t fully supported by their colleagues, peers and management,” says Harries.

Liberal abortion laws, but the problem is implementation

Researchers say the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1996, which gives women the right to an abortion on request, is considered one of the most liberal abortion laws in the world.

Although the legislation has not translated into optimal services for women in South Africa seeking abortions, medical historian Rebecca Hodes of the University of Cape Town says the problem is not with the law, but rather its implementation.

“The demand and supply of illegal abortifacient [medication that causes miscarriage] drugs is big business in South Africa and every major city [is] awash with advertisements for illegal abortions,” says Hodes.

Hodes and Jane Harries, from the Women’s Health Research Unit at the University of Cape Town, say more work needs to be done to create awareness in communities about the law and reproductive health services.

The law, says Harries, is very specific about the “legal requirements in order to obtain an abortion”. There has to be screening to determine the gestational age (how far the pregnancy is) to determine the type of abortion provided. According to the law, women have the right to an abortion on request in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and between 13-20 weeks if the health of the women or foetus is at risk or if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, and after 20 weeks if the health of the woman or foetus is at stake.

“The legalisation of abortion in South Africa has undoubtedly had a beneficial impact on the health of women. Despite this, numerous deep-seated problems with abortion access in South Africa’s public health sector remain,” says Hodes.

“The prevalence of severe morbidity as a result of unsafe abortions has remained steadfast as a result of the ongoing procurement of illegal abortions. Abortion should be a safe, accessible medical procedure that forms an integral part of South Africa’s comprehensive reproductive health programme.”

Ina Skosana was a health reporter at Bhekisisa.