By the age of 10, children’s ideas about gender, relationships and violence are largely set in stone.

If you’re waiting until your children become teenagers to talk to them about sex and gender, it may be too late, recently released research has found.

By the time a child reaches the age of 10, ideas about gender – or the social constructs that shape how we express ourselves as women, men and other gender identities – are largely cemented, according to the first-of-its-kind study on how children develop their understanding about gender roles.

As part of the study, scientists tracked 450 teenagers and their guardians over four years in 15 countries, including Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa. In a series of in-depth interviews, researchers asked participants for their thoughts about issues such as puberty, sexuality and dating.

Many life-skills programmes are aimed at older adolescents but the research suggests that, by the time a child reaches the age of 15, ideas about gender, such as who should pursue whom in a relationship, are mostly set for life. And the wrong ideas can leave teens at an increased risk of violence and HIV infection.

Findings from the study in Kenya and Nigeria also show that, although parents are willing to talk to children about sex, how they speak about it often reinforces problematic gender notions. For instance, when teenagers start menstruating, parents often don’t explain puberty. Instead, they tell them to stay away from boys because they’ll fall pregnant, says Beatrice Maina, a research officer at Kenya’s African Population and Health Research Centre.

“We found that parents like to instil fear in their children, especially the girls. If we don’t give our children the right information, we are leaving them for the wolves. They will find their own ways, which may be dangerous,” Maina says.

Similarly, the study found that parents worry more about girls than boys during puberty.

And, when parents do talk about puberty, it is often gendered: fathers mostly speak to boys and mothers talk to girls, says Bamidele Bello, the study’s field co-ordinator in Nigeria.

“This teaches teenagers that they can only talk to someone of the same gender regarding certain issues, further creating stereotypes,” she says.

Meanwhile, girls’ and boys’ feelings about their transition from children to young adults are mixed, ranging from shame and anxiety to pride. Many teenagers also report wanting increased privacy as their bodies change.

Maima explains: “They tend to hide their developing bodies from their parents and other family members in the household. The relationship they have with their bodies is volatile because they don’t fully understand what’s happening.”

‘The boy will pay some of the older boys to catch you’

The study also found that most teenagers believe boys should initiate romantic relationships. Many also say it is acceptable for boys to be domineering and, in some situations, violent.

In Nairobi, a 13-year-old girl said boys sometimes forcefully initiate relationships with girls.

“They [female friends] will tell you, you accompany them to go and meet a certain boy who says he is in love with you, so if you refuse … that is when they plan [with the boy] on how you will be caught. The boy will pay some of the older boys to come and catch you,” she said.

And what happens in the schoolyard can have lasting effects, warns Bello.

“While some [gender stereotypes] may look innocent when they [children] are still young, they will grow up with these beliefs, which will then affect their romantic relationships in adulthood. Men will continue to be the dominant partner in heterosexual relationships,” she says.

These gender norms can be linked, for instance, to women’s inability to negotiate condom use, which can put them at risk of HIV infection, she says.

A small 2016 study published in the journal Aids Care looked at couples in which men harboured “hegemonic masculine norms”, or beliefs that toughness, virility and dominance over woman are associated with being a “real man”. Couples that included men like these were less likely to use condoms consistently.

But condom use is not the only concern. Gender norms also play a large role in rape culture, says Bello. “Parents telling their girl children not to wear short skirts can eventually become a young woman blaming herself for being raped because of how she’s dressed.”

Breaking the cycle may start with changing the values of parents and influential adults in teens’ lives but this is no easy feat, says Tlaleng Mofokeng, a doctor and vice-chairperson of the South African civil society Sexual and Reproductive Justice Coalition.

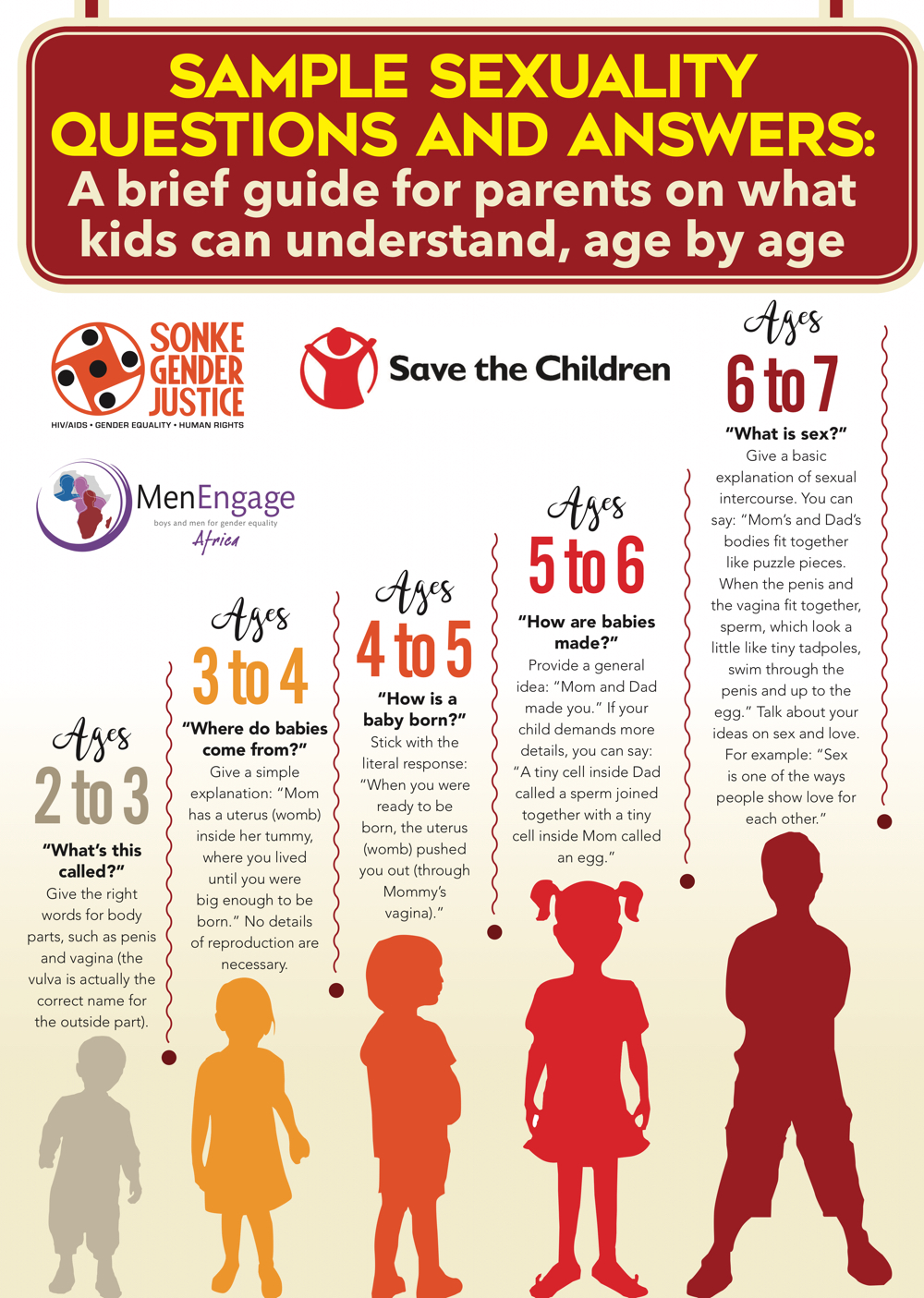

She says government programmes need to be better designed to teach parents how to talk to their children about sex, especially about issues concerning young black women. This could include educating parents on the science of puberty to help them to pass on the correct information.

“As a sexual reproductive activist and doctor, I think the problems we see in adulthood – lack of safe abortions, stigma – start when we are young. Children cannot be empowered if their parents aren’t empowered first.

“But changing the minds of older people takes time, innovation and decisive leadership in government,” she says.

Pontsho Pilane is the communications manager at Soul City Institute for Social Justice. Pilane was a health journalist at Bhekisisa from 2017 until 2019.