It’s World TB Day. Here’s why human rights and TB responses go hand in hand.

COMMENT

When the police arrived in their village in Nandi County in Kenya’s North Rift, Patrick Kipng’etich and Daniel and Henry Ng’etich didn’t think much of it. That is, until they realised the police were there for them.

What had they done?

Patrick, Daniel and Henry are working men with families, well liked in their communities. They were arrested and thrown in the police cells with other people accused of crimes.

Their crime? They had stopped taking their medicine for tuberculosis (TB).

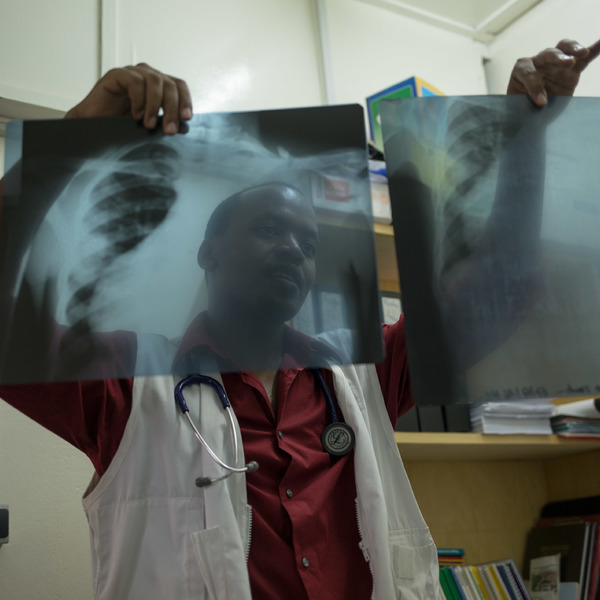

TB is preventable and curable but it now kills more people than HIV. According to the World Health Organisation, in 2016 alone, almost two million people worldwide died. More than 95% of the deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

In the same year, 10.4-million people became sick with TB. They all needed treatment but only about 60% ever received it. We missed 4.1-million people who were sick and unknowingly spreading the bacteria.

But legal barriers hamper the already inadequate global efforts to increase access to TB prevention and treatment services.

For instance, there are civil or administrative laws or regulations — such as public health or infectious disease laws — that are punitive, discriminatory or arbitrary as written or as applied to people with TB. These laws often use the same sanctions and penalties used under criminal law: imprisonment and heavy fines. But, unlike the criminally accused, people imprisoned and fined under civil law are not always afforded the same rights to due process.

In Kenya, Daniel and Patrick were sentenced to eight months imprisonment (or as long as it took to complete their six- to nine-month treatment) under the Public Health Act of Kenya — not the criminal law.

But that didn’t matter to their families. Their husband and father was in prison. Daniel’s wife and children abandoned him. They were criminals in all but name. And this simply for stopping their treatment.

Why did they stop taking their TB medicines?

Because they started to feel better and could no longer afford to walk or pay for transport to the clinic every day. It took time from their jobs as casual agricultural labourers. The TB programme failed them by neglecting to explain that, if they didn’t finish their treatment, they would continue to spread the disease and get sick again, or maybe get a worse, more complicated form of TB, known as multidrug-resistant TB.

But a Kenyan nongovernmental organisation, Kelin, intervened and won a landmark case in the high court in Nairobi in 2016. The court ruling declared the imprisonment of people with TB who stop their treatment unconstitutional. The judge even ruled that the Public Health Act itself did not authorise the use of prisons for the isolation of people with TB. The law had been applied in a counterproductive and unconstitutional manner.

There may be times when people with active, contagious TB decline treatment and refuse to take steps to stop the spread of the disease. In exceptional cases, involuntary isolation may be legally and ethically justified, but only in medically appropriate settings — not a prison cell — and with rights to due process and basic necessities, including nutritious food.

Many countries in Africa retain public health laws and penal codes inherited from the colonial era, with significant discretionary powers to enforce detention and coerce testing and treatment for TB, and to punish people for the negligent or reckless spread of communicable diseases like it. For example, in Lagos, the Public Health Act grants police the power to apprehend people with TB and HIV in the streets without any notice. A number of laws criminalise negligent or reckless conduct “likely to spread” disease in Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Uganda, The Gambia, Lagos State in Nigeria and Tanzania.

Even if seldom enforced, these laws contribute to a draconian legal environment, ripe for the discriminatory abuse of power against people with TB and their families. This kind of abuse does not only violate the human rights of people with TB, it is also counterproductive. It scapegoats and stigmatises people with TB as criminally culpable. It shifts the focus from the failures of health systems to provide access to effective and safe testing, treatment and care.

As political leaders prepare to convene in New York later this year for the first-ever United Nations General Assembly high-level meeting on TB, it remains clear that, if we are to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Agenda’s target to end the TB epidemic by 2030, we must fiercely protect and advance human rights. This means ensuring laws and policies are not implemented in an abusive, discriminatory way, but also by reforming laws that, on the face of it, grant unnecessarily broad powers to public health officials and law enforcement officers to the detriment of the TB response.

Brian Citro is an assistant clinical professor of law at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. Michaela Clayton is the director of the Aids and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa. Colleen Daniels is an HIV and TB consultant. Allan Maleche is founding executive director of Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network on HIV and Aids. Annabel Raw is the health rights lawyer at the Southern Africa Litigation Centre.