Newer, lifesaving drugs for South Africa’s “silent” killer aren’t yet available in the country.

Close to half of injecting drug users surveyed in South Africa are living with the potentially deadly Hepatitis C virus, a new study has found. But a drug that could cure them, and that is used in several countries, remains unavailable in South Africa.

The non-profit organisation TB/HIV Care Association released the study results on Tuesday. It is the largest ever survey to chart how many people in the country carry the virus. Hepatitis C causes liver damage and can be transmitted sexually or via shared needles, according to United States medical research organisation Mayo Clinic.

The study researchers tested about 3 400 people thought to be at high risk of contracting the virus because of potential risky sexual behaviour or sharing needles. The groups of people they focused on included men who have sex with men, sex workers and drug users (mostly those who inject drugs).

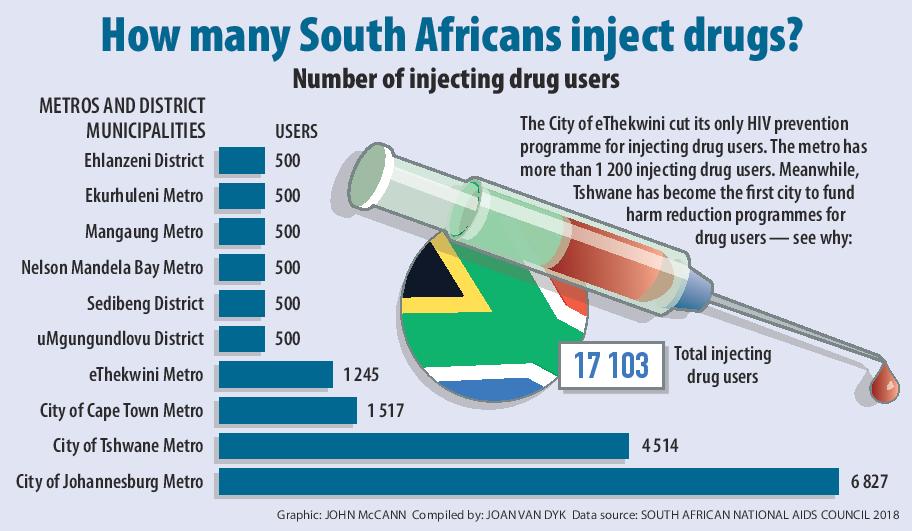

The research was carried out in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Mthatha, Pietermaritzburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban. Overall, 13% of people were found to be living with Hepatitis C and close to half of all these infections were among injecting drug users.

Almost 40% of the study’s participants were also HIV positive. The survey revealed high rates of Hepatitis C and HIV co-infection (29%) among Pretoria drug users, which TB/HIV Care Association strategic advisor Andrew Scheibe attributes to the city’s long-standing injecting drug use culture.

In 2017, Tshwane became the first city in Gauteng to offer legally prescribed medication, known as opioid substitution therapy (OST), that helps people to reduce or stop using drugs such as heroin without debilitating withdrawal symptoms. OST helps to decrease illegal drug use, overdose deaths and new HIV infections among people who use drugs, a 2011 study published in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization (WHO), has found.

[WATCH] Chasing the dragon, stalking a virus: Life, heroin and Tshwane’s needle exchange

Researchers also showed that 4% of those surveyed in South Africa had Hepatitis B, a virus that — like Hepatitis C — can be spread via contact with sexual partners or infected needles and damages the liver. Unlike Hepatitis C, there is no cure for Hepatitis B but vaccines can protect people from contracting it, the Mayo Clinic says.

The study recommends expanding access to Hepatitis B vaccination for high-risk groups as well as OST and needle exchange programmes that can reduce the risk of infection for people who use drugs.

Globally, more than 1.34 million people died from viral hepatitis in 2015 with deaths outpacing those caused by HIV, according to the WHO’s 2017 Global Hepatitis Report.

But hepatitis has been largely ignored in South Africa, Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital’s head of infectious diseases Sarah Stacey warns.

“We should be worried about hepatitis because it kills people.”

Historically, Hepatitis C treatment has been priced out of reach of most — it can cost up to R120 000 for a year’s course. Newer medication, however, could drop that price by up to two-thirds, according to international nonprofit the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative.

But newer drugs have not yet been approved for use by the South African Health Product Regulatory Authority, the country’s medicine regulator. Once these are registered, they will be available in certain sectors, but cost will still be a major barrier to widespread access, Schiebbe warns.

The study was funded by the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb, which manufactures the Hepatitis C medication, daclatasvir.

South Africa’s draft hepatitis treatment and prevention guidelines have yet to be passed by the national health council, national health department medical advisor Kgomotso Vilakazi-Nhlapo says. She estimates an extra R4-billion will be needed over the next five years to decrease hepatitis infections.

Vaccinating people at risk of Hepatitis B, and expanding health services such as OST and Hepatitis C treatment — when it becomes available — are part of the country’s national HIV plan.

But the implementation of the strategy remains the responsibility of provinces, explains South African National Aids Council’s Nevilene Slingers.

“Provinces [need to] make sure that the drugs and money to buy the drugs is available.”

Pontsho Pilane is the communications manager at Soul City Institute for Social Justice. Pilane was a health journalist at Bhekisisa from 2017 until 2019.