We are facing possibly the greatest health threat of our time: drug-resistant infections. But here’s why there’s hope the world can change course.

COMMENT

The world is facing possibly the greatest health threat of our time: the rise of drug-resistant infections. Since their introduction in the 1940s, antibiotics have been relied upon to treat and prevent a huge variety of conditions. We use them to treat everything from small cuts that have become infected to preventing infections in people undergoing surgery.

But we are in danger of reaching a place where even common infections once again become untreatable.

Around 700 000 people die already each year globally as a result of drug-resistant infections, found a 2016 report by the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance written by a team of experts at the behest of the United Kingdom government. This is a figure that could rise to up to 10-million globally by 2050 if action isn’t taken to limit the overuse of existing drugs and develop new ones.

And while this problem affects every country in the world, it is lower and middle-income countries that will bear the brunt of this burden. An additional 24-million people in these countries will be pushed into poverty if we cannot stop superbugs, a 2017 World Bank report estimates.

This is a future we can avert – but only if we take effective action, and now.

The problem of drug-resistant infections is genuinely global, but the most successful action will fulfil local needs. This is because our cultural, social, economic and epidemiological contexts shape the problem of antimicrobial resistance in communities, districts and countries. They must also shape our solutions.

Interventions developed in northern Europe, for example, are unlikely to adequately address the needs of patients in much of Africa or Asia.

Luckily, many of the worst affected countries, including those Africa, are pioneering solutions that could keep us ahead of the superbugs.

In Tanzania, for example, local retail drug shops known as duka la dawa are often used by communities to buy medicines such as antibiotics. Since 2003, the country’s Accredited Drug Dispensing Outlets programme has been training shop owners to safely sell prescription drugs, including antibiotics, to increase awareness and promote appropriate use in often under-served rural areas of the country.

As a result, more than 12 000 accredited drug dispensing outlets serve Tanzania. Sellers have been trained about antimicrobial resistance and the dangers of misusing antibiotics. Armed with posters, dispensing guides, counter-top information cards and rubber stamps to label medicines, vendors can educate their customers and promote the proper use of antibiotics.

Tanzania’s programme significantly decreased the availability of unauthorised medicines, a 2014 study published in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice found.

The study reviewed hundreds of community dispensary records and interviewed dozens of sellers and customers. It found that after training 95% of patient medication was correctly labelled with the drug’s name – before training about one in five (18%) of drugs were properly marked.

In less than one year, almost all sellers surveyed met the six main criteria for good dispensing practices that help ensure patients know what medicine they are taking home, how to take it and any side effects to expect.

Importantly, the inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics for common diarrhoea decreased by almost 70%.

At the same time, Tanzania’s scheme has also increased the availability of antibiotics for people who really needed them as sellers were more likely to have approved antibiotics in stock after training.

This innovative approach, using modest resources, has been so effective that it is now being scaled up across Tanzania – and is being replicated in countries such as Uganda, Liberia, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia and Bangladesh.

It’s just one example of pioneering work that is already going on to limit the impact of antimicrobial resistance in villages, towns and cities across the world – many of which point to the role that communities can play in educating people about the proper use of antibiotics.

In Bangladesh, community-based volunteers have been trained on the responsible use of antibiotics, and communication skills. These volunteers run regular participatory community dialogue sessions to discuss the specific issues relating to antibiotics that affect the community and make collective decisions on the best way to address them.

With 55 volunteers currently, the scheme is small, but this community-based and cost-effective approach has the potential to be scaled up in Bangladesh and applied in other countries as well.

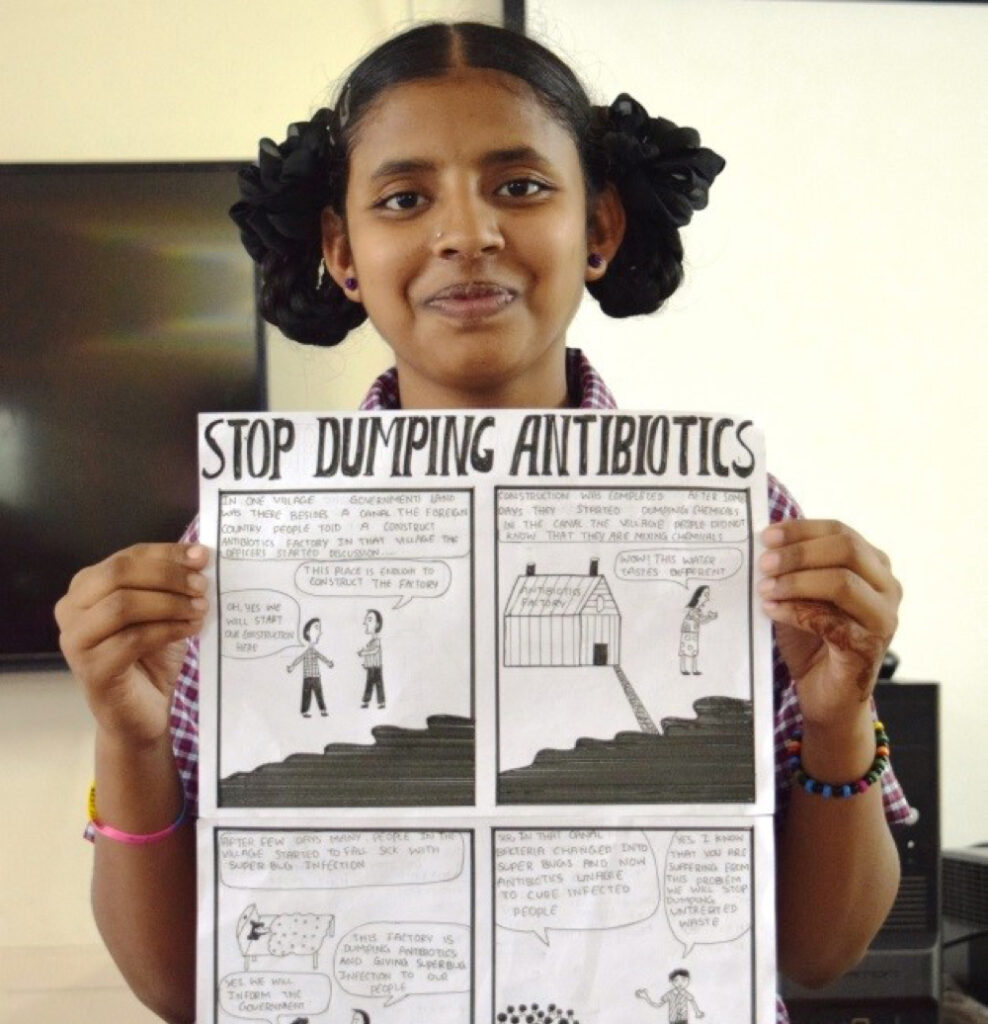

Meanwhile, in India 9th grader Akansha is weaving a story about an exciting race. Only this one, depicted as a comic strip is in her tummy and pits the good “bugs” against the bad as they compete under the watchful eye of the “antibiotic master” for the “superbug trophy”.

Akansha is one of many young children who are part of the country’s “Superheroes Against Superbugs”. The project spreads awareness of antibiotic resistance among young children through comics, storytelling and role play. The programme is hoping that children will ferry the messages they learn there home to their parents and the wider community.

Not every innovation can be the next big thing, but from these, and the many other projects around the world, we are starting to learn valuable lessons through trial and error. These are lessons the world will share next week in Accra as part of the second Call to Action on Antimicrobial Resistance event.

Co-hosted by the global charitable health foundation Wellcome Trust and the Ghanaian, Thai and UK governments as well as the World Bank and UN Foundation, the event will bring together policy makers, health professionals, academics, civil society and the private sector to discuss what is needed to stem the tide of drug resistance.

By sharing the examples of initiatives like Tanzania’s Accredited Drug Dispensing Outlets programme, we can inspire further innovative local approaches to tackling the rise of superbugs across the world.

Too often, low- and middle-income countries are painted as the root of the superbug challenge – when in fact their insight, involvement and innovation will be the best source of solutions to benefit us all.

So we must turn to some of the pioneering innovations emerging locally to guide us towards what works and what might be replicated elsewhere. It will be important to see what locally-developed programmes countries embrace and what resources countries might need to replicate successful programmes.

Antimicrobial resistance threatens to turn the clock back on decades of medical progress, but there is still time to change course.

Timothy Jinks is the head of Wellcome Trust’s Drug Resistant Infections priority programme, leading Wellcome’s efforts directed at reducing the threat of antimicrobial resistance. Follow the project on @Wellcome_AMR.