Does sex work legislation have an impact on violence and the spread of HIV? We follow two women who operate in opposite worlds to find out.

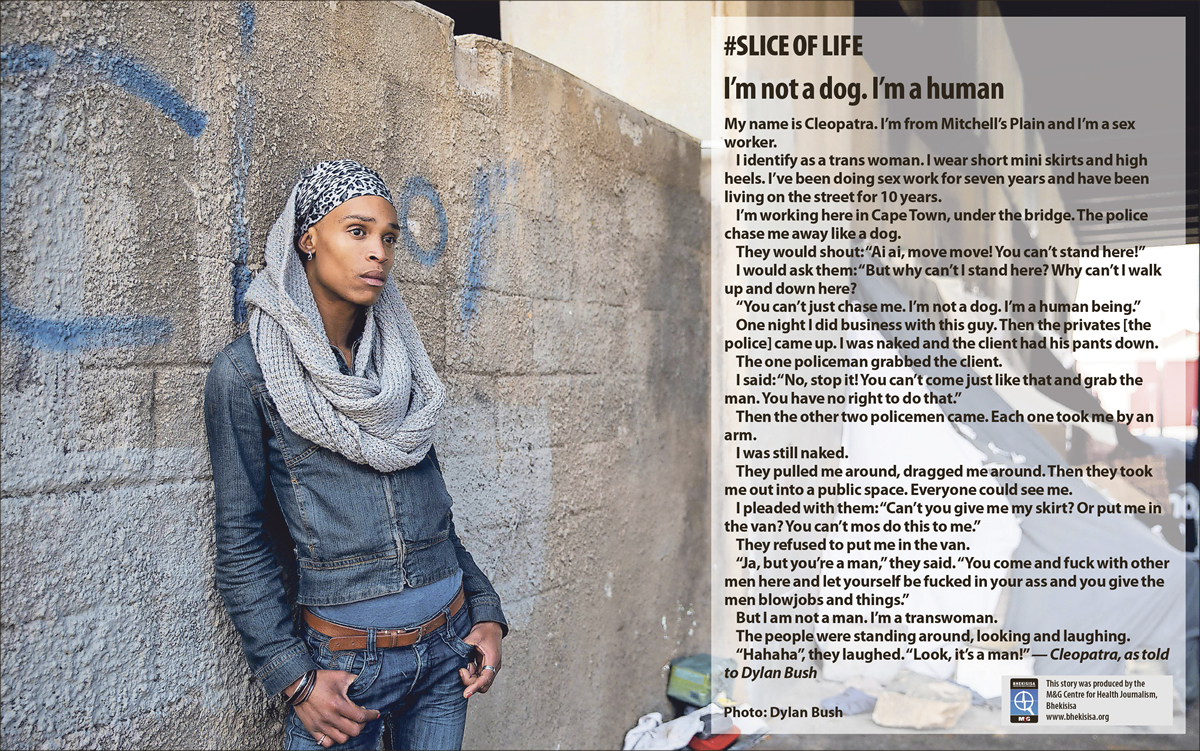

It was about 8pm on a cool spring evening when the white police van shuddered to a halt alongside Nosipho Vidima.

She was at her usual post in the tree-lined street in Morningside, Durban. Vidima was wearing a short, blue dress and leaning on the fence of one of the suburb’s Victorian-style homes.

She recognised the police officer. At least once a week he would drive past her corner and make smug remarks.

But on this night, the cop — in his late twenties — was more brazen.

“Why are you here?” he yelled from the driver’s seat.

Vidima didn’t answer. She looked the other way.

Infuriated, the officer exploded: “You’re too clever for your own good! Who do you think you are?”

He got out of his vehicle, slammed the door and threw open the rear lock-up section.

“Get in!” he bellowed.

Vidima, 28 at the time, was an opinionated woman. She knew her legal rights better than most of her colleagues because she was a part-time law student.

But Vidima was defenceless.

She was practising an illegal profession in the city that research shows has one of the highest concentrations of sex workers in South Africa.

Although Vidima knew that the laws that criminalise sex work in the country — the Sexual Offences Act and the Sexual Offences and Related Matters Amendment Act — require intrusive police methods such as entrapment to secure a conviction, this knowledge didn’t help her.

In the real world, the policeman had all the power.

“I was too scared to fight him, so I got into the van,” she recalls.

It was sticky hot and filthy inside the van. Vidima wondered if she would be kept in a holding cell at the CR Swart Square police station in town, like so many times before.

But as the vehicle snaked through the streets she saw the officer was driving towards the Burman Bush Nature Reserve, a park in Morningside.

He stopped at an isolated area, unlocked the back and instructed Vidima to get in at the passenger side.

Unfastening his pants, he commanded: “Blow job, bitch!”

Vidima took out a condom, but the officer refused to put it on. “Instead, he forced my head back and forth by pulling my hair — until I was gagging.”

Halfway through the act, in the pitch dark, the policeman ordered her: “Take off your panties and turn around. We’re now going to do what you do on the streets.”

Then he shoved his penis in her anus and raped her.

Outside the air conditioned cubicle in 19 Oudezijds Achterburg street in Amsterdam’s red-light district, near the city’s oldest church, long shadows fall from the tall, thin buildings lining the inner-city canals. The summer sun hangs low in the pale blue sky.

Elsa Wilson*, 25, sits on a bright red chair with high legs. She’s clutching a bottle of mineral water.

“I fuck people for money,” she smiles. “Someone will come up and say, ‘How much?’ I say I offer a blow job and vaginal sex for 50 Euros (R780) and it’s either yes or no.”

The buying and selling of sex, as well as the operation of brothels, is legal in the Netherlands.

“If you say yes to my price, you come in, and we have a good time — in a safe space,” Wilson explains.

Nearby, the Oude Kerk (Old Church) bells chime three o’clock with heavy gongs that tremble over the Oudezijds Achterburg gracht’s glinting water.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in late August and people on bicycles with red and green baskets weave their way through throngs of tourists and the scent of tulips.

Wilson slides off her high stool, flicks her blond hair and says: “I like that I’m able to offer a service that makes people feel physically good. I really like the connection.”

The young sex worker’s heavy makeup makes her appear older than her years. She’s dressed in an olive green corset with black lace detail suspended beneath a cerise bikini top.

“Sex work is self-fulfilling,” she says. “It’s also good money.”

Wilson, who speaks with an American accent, is originally from Austin, Texas.

She and her husband, a computer analyst, moved to Amsterdam in March on a Dutch-American Friendship Treaty visa that allows US citizens to migrate to the Netherlands as “independent entrepreneurs”.

Because sex work is legal in the country, Wilson could obtain a visa on the basis that she planned to open a sex work consultancy in Amsterdam. Her visa allows her spouse to work as well.

“My husband helps me to get ready for work in the mornings,” she says and leans against the charcoal tiles that decorate the walls of her cubicle. Then she crosses her feet, which are wrapped in shocking pink shoes with towering heels, and drawls: “I’ll be like, ‘Which of these lipsticks, babe?’ and he’ll help me choose.”

Wilson started sex work when she was 17. “In the US,” she explains, “it’s much harder than this.”

“Sex work there is [mostly] illegal, so no sex worker is safe. If you get raped, you can’t call the police because they would arrest you and probably rape you too.”

Two years ago, about 13 000 kilometres away from Amsterdam, the reality of being a sex worker in an unprotected environment descended on Sipho*, a woman in her mid-thirties.

All aspects of sex work — the buying and selling of sex, as well as making a living by means of sex work by being a pimp or operating a brothel — are illegal in South Africa.

Sipho’s beat in western Tshwane was a place known as “The Bush,” a scrub-covered field. The unfenced grounds, from where sex workers have been selling their services for years, has a reputation for being a dangerous place.

Operating in this kind of setting is common for sex workers in countries where the profession is criminalised. “The threat of arrest does little to stop sex workers [from doing business],” a 2006 South African Crime Quarterly study found. “Instead, it forces them underground and into situations that are potentially even more dangerous.”

In the early autumn of 2016, a man posing as a client throttled and raped Sipho at knifepoint at “The Bush”.

Her story was documented by the researchers of a Sonke Gender Justice and Sex Workers Education Advocacy Taskforce (Sweat) report that was released in 2017.

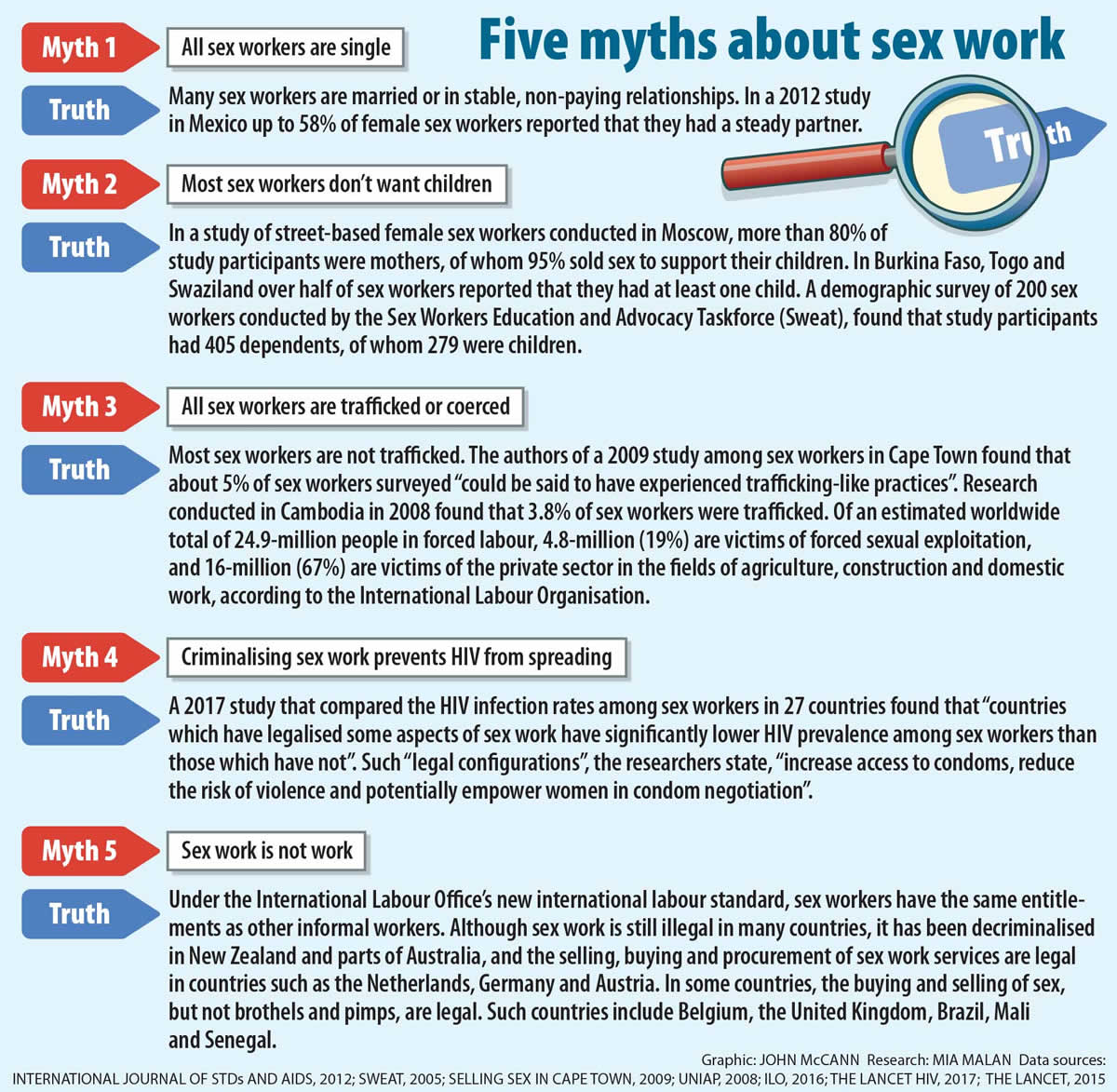

Numerous studies have shown that sex workers who trade in countries where such transactions are illegal, experience considerably more physical and sexual violence from clients than in states where sex work is either legalised or fully decriminalised, as regulation helps to create safer work environments.

Female sex workers in the US are, for instance, 18 times more likely to be murdered than non-sex workers, a 2004 study in the American Journal of Epidemiology, revealed.

In South Africa, around one in five female sex workers in Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town had been sexually assaulted in the year prior to being interviewed, the 2014 South African Health Monitoring (SAHMS) female sex worker survey found. About half of the workers in these cities had experienced physical violence.

The incident involving Sipho was not the first time a sex worker had been raped at “The Bush”.

Two of Sipho’s colleagues told the Sonke and Sweat authors that they too had been violated by a man with the same distinctive scarring on his chest that Sipho recalls her attacker having.

But sex workers were also adamant that their rapists were frequently the police themselves. One in three of the 57 sex workers surveyed reported they had been raped by policemen, and more than half said police officers had demanded bribes from them in exchange for escaping arrest or abuse.

“I have lost count of how many times I’ve been raped by the police,” says Vidima, who became Sweat’s lobbying officer shortly after her Morningside rape ordeal in 2013. “I’ve become numb. If you say no to a police officer asking for sexual favours, he threatens you. It turns the sexual favours to abuse and rape straight away.”

From interviews with a further 61 sex workers, the Sonke and Sweat researchers documented horrific examples of police forcing the women to have sex with animals, compelling them to eat used condoms and refusing to assist them after they had reported abuse at the hands of clients.

“Such treatment reflects a common perception that due to the work they do, sex workers cannot be raped or are somehow deserving of rape,” the authors conclude. “Police therefore seldom want to open a case, even when a sex worker wants to try and lay a complaint.”

Five months prior to Sipho’s rape, in November 2015, a sex worker, Queen Koketso, was found dead at “The Bush”.

Koketso’s co-workers went to the police to report the murder, as well as the presence of a suspicious man in the area. But they say the officers refused to take their statements. Neither did the police take up an invitation to attend Koketso’s funeral to record statements from women who lived and worked in the vicinity.

Instead, sex workers told researchers, the police raided “The Bush” two weeks later, setting fire to their shacks and destroying their personal possessions.

Bhekisisa asked Gauteng police spokesperson Lungelo Dlamini whether a murder docket had been opened for Koketso and whether the police took potentially relevant statements from her colleagues. We also sent him other written questions, including a request to respond to allegations that the police had razed sex workers’ homes, and if so, to explain the reasons.

Dlamini acknowledged receipt of our questions, but never responded.

Sipho never reported her rape to the police. Neither did her two colleagues.

Said national police spokesperson Vish Naidoo: “If sex workers don’t lay a complaint, how can we investigate? If they don’t report abuse or a lack of (police) service, it’s as if it never happened.”

But Sipho echoes the feelings of many sex workers in South Africa: “Even though the man raped me and stole my cell phone, I am more frightened of the police than I am of that man.”

At the My Red Light brothel in Amsterdam, a soft drizzle has transformed the grey cobblestones outside Wilson’s window into polished marble.

She’s scanning a WhatsApp message on her phone.

She takes a sip of water, smooths her black stockings and says: “I’m a whore. I wanted to make sure I’m based in a country where I’m legally allowed to practise the career I’ve chosen, so that I have the right to complain when I’m treated unfairly.”

My Red Light is a window brothel — sex workers recruit clients who pass by from behind cubicles with glass doors. At the back of her nook there’s a door that leads to a corridor with rooms where clients are served.

If a customer becomes abusive, a worker can press one of the panic buttons that are a feature in every room.

“That will result in the landlord or police arriving within five minutes,” Nadia van der Linde of Amsterdam’s Prostitution Information Centre, a nonprofit organisation started by sex workers, explains. “But mostly it’s the sex workers themselves who are first on the scene to help their peers.”

Brothel owners in the Netherlands have to comply with stringent government rules. Window brothels, for instance, require operational licenses, can only do business in designated areas and must close between 6am and 8am.

Even though sex workers in these brothels work for themselves, and not for the owners of the buildings, the proprietors are not permitted to rent out rooms to anyone younger than 21, which is the legal age for sex work in Amsterdam. They also have to confirm that workers have permission to work in the country and are registered with the chamber of commerce for tax purposes.

Sex workers pay 21% VAT on the services they sell and up to 35% in income tax.

“We often jokingly say that the Dutch government is our biggest pimp because we pay tax on at least half our earnings,” van der Linde laughs.

By law, landlords have to conduct interviews with workers wanting to do business from their premises, to determine whether they’re sufficiently self-reliant. Van der Linde explains: “This involves evaluating whether workers are able to communicate in Dutch, English, German or Spanish, so that they are equipped to negotiate with clients in at least one of the most commonly spoken European languages.”

[LISTEN] This mom became a sex worker and her daughter is fine with it

Like her colleagues, Wilson sees about six to eight clients a day.

Inside her cubicle, where she’s leaning with her back and one leg on the wall, the sex worker looks up from her phone. Across the street, next to the canal, a man in his late forties hovers in the thin mist.

Wilson is sure she’s seen him before.

A thick wedding band constricts his ring finger. The man rubs one of his arms and scouts around nervously. Then he uses a small cloth to wipe his gold-framed glasses, hitches up his bermuda shorts and strides across the lane.

The Prostitution Information Centre reports that, on average, customers spend between six and 15 minutes with sex workers and they’re mostly married and in their 30s or 40s.

“I rent a window for 80 Euros [R1256] in the day or 160 [R2512] Euros at night,” Wilson explains. “I can deduct these costs from the taxes I pay.”

When the glass door next to her window clicks closed behind the man, Wilson clambers back onto her chair, freshens up her fuschia lipstick and says: “I myself decide when I want to work and whom I’d like to work with. I can do whatever I want, whenever I want.”

In 2017 Cyril Ramaphosa, the country’s then deputy president and chairperson of the South African Aids Council (Sanac), launched the country’s fourth national HIV plan. The document left sex workers, concerned scientists and human rights activists fuming.

Their outrage was sparked by the omission of what they, as well as international health bodies such as UNAids and the World Health Organisation, consider to be a crucial component for HIV prevention among sex workers: the decriminalisation of their means of income.

It was the first such five-year plan to exclude arguments advocating for decriminalisation. The strategy, coordinated by Sanac but over which cabinet holds final approval, contrasted with the national HIV sex worker plan — also launched by Sanac — which strongly endorsed decriminalisation.

Female sex workers, particularly those operating in countries where sex work is illegal, are significantly more likely to be infected with HIV than other women.

This is because they have a higher number of sexual partners and experience more violence, the authors of 2015 research in The Lancet explain, resulting in them “giving higher priority to their safety and survival than less immediate concerns such as HIV prevention”.

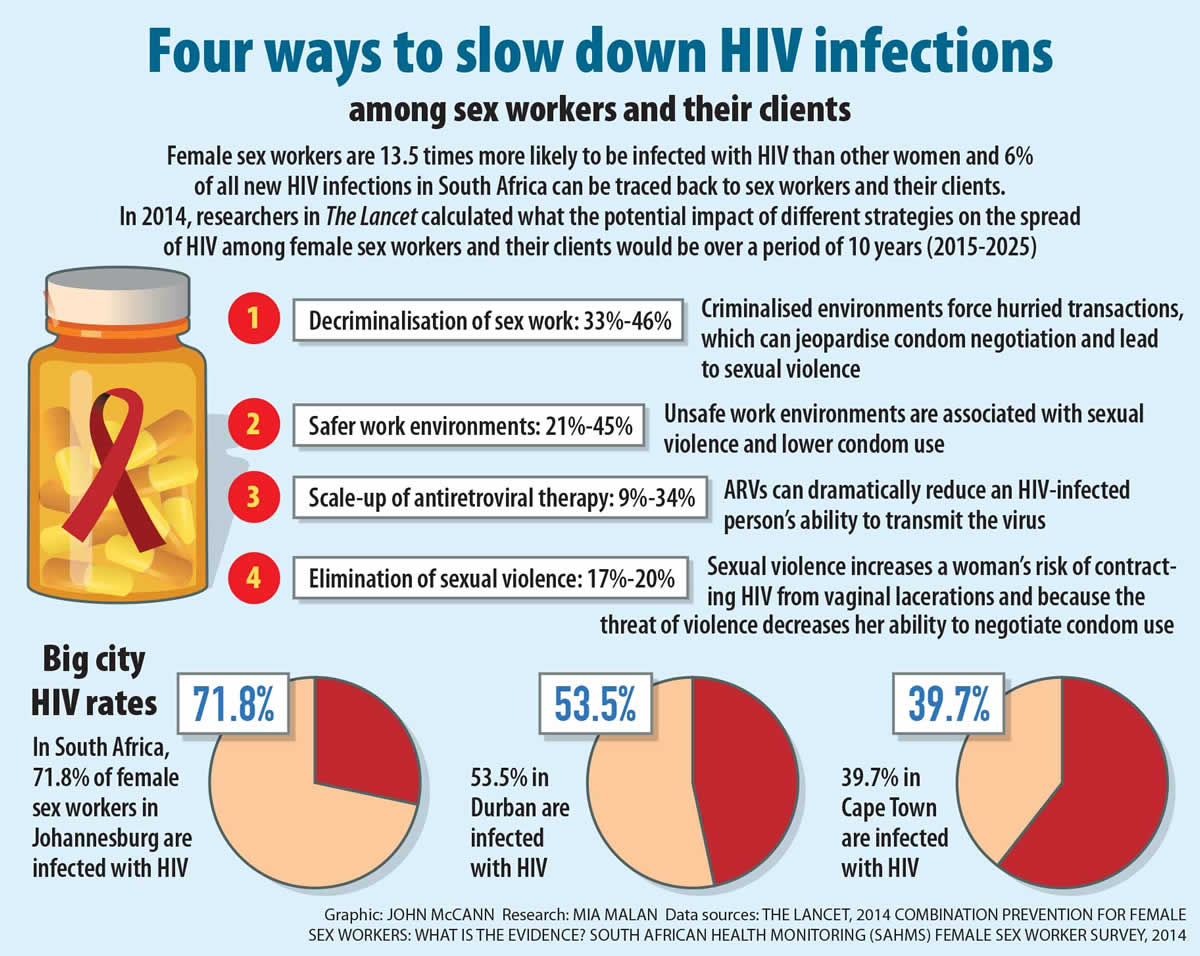

HIV infection rates among South Africa’s estimated 138 000 female sex workers are indeed very high: in Johannesburg almost three quarters (71.8%) of workers have tested positive and in Durban just over half, according to the SAHMS.

Decriminalising sex work — the removal of all laws against consensual adult sex work — scientists argue, will slow the epidemic among workers and their clients dramatically.

Modelled estimates published by The Lancet in 2015 show that this legal model has the potential to avert more infections than any other HIV prevention strategy among sex workers and their clients over the decade — between a third and almost half of the world’s new infections — because of the “combined effects that decriminalisation would have on violence, police harassment, safer work environments and HIV transmission pathways”.

Activists say decriminalisation was a prominent feature in the draft of the 2017 – 2022 HIV plan that they provided input for. But, somewhere between that version and the one Cabinet approved, the concept inexplicably disappeared from the document.

Health experts maintain that a mix of morals, politics and conservatism have trumped evidence. And the controversy doesn’t end here.

Two weeks after the full version of the HIV plan was released, South Africa’s law reform commission — a body that advises the justice and constitutional development minister on how to improve and develop the law — published a long-awaited review of “adult prostitution”.

To the chagrin of civil society, the commission also recommended that sex work should continue to be fully criminalised. As a second option, it proposed a widely criticised model, the partial decriminalisation of sex work, under which it would no longer be a crime to sell sex but it would be an offence to buy it.

Also known as the end-demand or Nordic model, partial decriminalisation has been shown to increase violence towards sex workers and decrease access to health services — two crucial elements that determine how fast HIV spreads.

But, in December 2017, on the final day of the ANC’s national elective conference, sex workers and scientists received new hope when the party announced it had resolved to decriminalise sex work.

Tlaleng Mofokeng is a reproductive health doctor in Johannesburg and also the deputy chairperson of the advocacy group, the Sexual and Reproductive Coalition of South Africa. She believes sex work should not be criminalised. “Just because something is undignified and you would not do it, doesn’t mean those who do it must be criminalised and punished,” she says. Mia Malan spoke by phone to Mofokeng.

However, the optimism among activists and other concerned parties has since faded.

Almost a year later, the deputy minister of justice, John Jeffery, whose department released the law reform commission’s report, told Bhekisisa the announcement was inaccurate, “if one looks closely at the wording of the resolution”.

The resolution reads: “The calls to decriminalise sex work must be subjected to a high level discussion and engagement with relevant multiple stakeholders, and to continue to engage society on this to determine the societal norm. Sex workers must be protected.”

Jeffery says “internal discussions between government departments” are happening, and these will be followed by further public discussions about decriminalising sex work.

But he adds that it’s unlikely that the consultation process will be concluded before next year’s elections.

In another twist in July, the same month that fresh evidence of the harmful effects of partial decriminalisation on the safety of sex workers in France and Canada was released at the International Conference on Aids in Amsterdam, the National Council of Provinces (NCOP), unanimously voted in favour of this model and adopted a resolution in support of it.

Although the motion doesn’t extend the body’s law making abilities with regards to sex work at this stage, as a bill hasn’t yet been tabled, it does carry weight because it represents the view of Parliament’s upper house. An NCOP committee has also visited Sweden — the country that pioneered partial decriminalisation — to research the model.

These developments have again angered and disappointed civil society.

The deputy chair of the Sexual and Reproductive Justice Coalition, Tlaleng Mofokeng, warns: “When prejudice, culture or theology carry more weight than scientific evidence, it literally means death.

“Sex workers have a constitutional right to operate in a safe environment and to access health facilities without fear of discrimination. Partial decriminalisation deprives them of those rights.”

At My Red Light, Elsa Wilson and a client are occupying one of the brothel’s dimly lit rooms.

She’s renting an upstairs room that contains a double bed covered with a sheet of blue plastic, an oval bath, a shower, basin, disinfectants and a bright red toilet.

A soft red sheen covers the bath.

“The theory is that a combination of red, blue and white light does wonders for your skin and all the girls know that,” Marcel Heyman, one of the brothel’s board members, explains. “How work environments impact on their appearance is really important to sex workers.”

The brothel, which has 14 windows spread across four buildings, and also an online booking system, opened in May 2017. It’s the only facility in the city that’s run by sex workers themselves.

They chose the decor along with interior designers and the profit made from renting out rooms is used to invest in projects to improve the workers’ social status.

“We’re establishing a safe place where sex workers are able to be themselves and where they have a say in the way they want to fulfill their jobs,” states the brothel’s website.

My Red Light also provides clean sheets and towels for sessions with clients. “It makes my job so much easier,” says Wilson. “It means I don’t have to bring a ton of extra things with me and I can focus more on whether I have enough condoms and lubricant.”

She smiles.

“It’s like a chef in a restaurant. You want to focus on the quality of the food and the health and safety thereof. You don’t want to worry about bringing along tables, chairs, tablecloths and silverware every day, because that takes the focus away from the more important aspects of the service you’re providing.

Against the black wall of Wilson’s room, above the basin, a silver-framed notice hangs. Its heading is: “House rules for visitors.”

Rule No 3 reads: “You may not request unsafe sex.”

Wilson professes: “I never have sex with a client without a condom. Never.”

Amsterdam’s government-funded P&G292 sex worker clinic advises workers to test voluntary once every quarter — it’s not required by law.

“I do an HIV test every second month,” says Wilson. “It’s more than most people, but it’s a free service, so I might as well use it.”

P&G292 provides workers with far more than HIV tests. It also employs counsellors and social workers who help them to report abuse or exploitation, and provides English and Dutch language classes, self defence lessons and assistance with tax registration.

“Our goal is to enhance the emancipation and self-reliance of sex workers,” the clinic explains on its website. “Every human being has the right to choose an occupation and engage in work freely.”

The result?

According to the July study, the HIV infection rate among female sex workers in Amsterdam is 0.5%.

For bacterial sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis, the prevalence rate is 9% — half that of the general female population in the city in 2017, the municipal health department’s latest figures reveal.

Bacterial sexually transmitted infections can make it easier to contract HIV, or, put differently, increase the efficiency of HIV transmission. It is therefore important to treat these as part of HIV prevention.

At My Red Light, Wilson is documenting the work she’s done that day, for tax purposes. Like most of her colleagues she uses an Excel spreadsheet and also employs a bookkeeper.

It’s just after 6pm; her work day usually ends at 7pm. The night shift workers clock in at 8pm, to work until 6am the next morning.

[WATCH] All the ways the world polices sex

The legalisation of sex work, as in the case of the Netherlands, Senegal and Mali, is slightly different from decriminalising the profession: When it’s legalised, the state is the main regulator of the industry and decides under which conditions sex work takes place. With decriminalisation — for instance, in New Zealand and parts of Australia — sex workers are more empowered to make decisions about the way in which they would like to work.

But even when sex work is legalised, particularly when all aspects — the buying, selling and procurement — are legal, the researchers of a 2017 study in The Lancet HIV found significantly lower HIV infection rates among sex workers than in countries where the profession is criminalised.

The authors of the international Aids conference study concur: “The legal nature of prostitution [in the Netherlands] contributes to easy access of female sex workers to health and social services. These factors might explain the low HIV prevalence of 0.5% among female sex workers in Amsterdam compared to other countries.”

Condoms: One department giveth, the other taketh them away

In South Africa, where the government supports 25 NGO clinics that provide services to sex workers, but within a criminalised environment, a radically different scenario is playing out.

In Johannesburg, not even a quarter of sex workers who know they’re HIV positive have taken up the health department’s offer of free antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, the SAHMS shows.

In Durban only about a third have chosen to use ARVs and in Cape Town less than half.

“The minute one criminalises an activity, health services become less accessible to the people who are involved in that activity because of fear of discrimination,” Linda-Gail Bekker, deputy director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the University of Cape Town, explains. “It’s tough for policymakers to get, but the evidence is undeniable.”

The uptake of ARVs plays a critical role in the fight against HIV among sex workers: the pills don’t just keep people with HIV alive; they can literally prevent the spread of the virus.

When the medication is used correctly, studies have found, it reduces the amount of HIV in an infected person’s body to such low levels that they become “virally suppressed”, making it scientifically impossible for them to transmit the virus.

The national health department’s deputy director general for HIV, Yogan Pillay, acknowledges: “From a public health perspective it’s a no-brainer that South Africa needs to decriminalise sex work.”

But he adds that it’s an “emotive” and for some people “a moral issue that requires a national conversation”.

For Pillay’s department, however, the criminalisation of sex work directly impacts on its ability to reach its condom distribution targets.

The sex worker plan stipulates that, between 2016 and 2019, the health department had to have distributed 11.8-million male and 3.9-million female condoms among sex workers. But the police regularly seize these from workers as “evidence” of illegal sex work.

The Sonke and Sweat researchers have documented many such cases.

The situation has left the country’s president perplexed.

“It is a matter of concern that while the department of health supplies sex workers with condoms to protect them from HIV, pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, it is not uncommon for police to confiscate these condoms,” Ramaphosa warned at the launch of the sex worker HIV plan in 2016.

“We have one arm of the state providing a very necessary service and another organ of the state taking that very service away.”

On the glass door of the Prostitution Information Centre in Amsterdam, beneath a heart-shaped cushion hanging on a string, a poster with a red umbrella looms. “The right to be PROUD,” is scrawled below it.

PROUD is the Dutch union for sex workers. It provides its members with free legal services and workshops.

A short woman in her late 40s is drinking coffee at one of the centre’s wooden tables, next to a tin of windmill cookies.

Her auburn hair is tied up in a ponytail.

Karin, who prefers to keep her surname private, is a sex worker of a different kind: she specialises in providing services to physically and mentally disabled people.

PROUD taught her about her employment rights as a sex worker.

But it’s not her only job.

“I’m also a professional nurse,” she explains. “It is in my day to day duties in this profession that I noticed there were many patients who can’t have sex like other people.”

Karin contacted an agency that focuses on the sexual needs of disabled clients and two days later she had her first job.

“My nursing skills come in handy, because I know how to handle people in wheelchairs and understand people with special needs,” she says.

South Africa’s law reform commission, however, doesn’t recognise sex work as “decent work”. “The illusion that prostitution is a choice is manipulative and deceptive,” it states in its report.

[WATCH] Nurse: ‘I had to supplement my income. That’s when I got into sex work.’

“The fact that money or any other financial or other incentive is exchanged cannot disguise what occurs in prostitution — the bodily and psychological violations involved are in fact sexual abuse and harassment.”

The Sexual and Reproductive Justice Coalition’s Mofokeng, who works with sex workers as a reproductive health doctor, disagrees. “Exploitation is not inherently present in sex work, although criminalisation makes workers more vulnerable to it. Sex work is remuneration for sexual pleasure given by consenting adults. If there’s no consent, it ceases to be sex work.”

Karin gets paid by the hour and travels to her clients. The agency charges institutions who refer clients €170 (R2 670) for an hour-long session and she gets €125 (R1 960) of that fee.

She explains: “A session is a minimum of an hour because you usually have to first make sure the client is comfortable and sometimes teach them what to do.”

A 2009 research study of the Institute for Security Studies that surveyed 164 sex workers in Cape Town found that “very few sex workers consider themselves to be victims of anything more than circumstances”.

“We therefore believe that foisting a victim label on people working in this industry, simply because many regard the work as morally repugnant, is not only inappropriate, but also disempowering,” the authors concluded. “Sex workers would rather have their work treated as a legitimate job with the legal protection that comes with that.”

But, Karin says, even within a legalised environment, there’s discrimination.

She crosses her legs, and dips a cookie in her coffee.

“If you’re at a dinner party, and someone says what’s your day job, it’s better to say I’m a nurse. The stigma is still there, you don’t want everyone to know.”

In Morningside, the policeman who had raped Vidima, ordered her back into his vehicle’s rear before dropping her off at a petrol station near where he’d found her.

As the van disappeared into the late night traffic, Vidima walked into the garage shop and bought a box of Stuyvesant Reds cigarettes.

She sat down on a low wall nearby, lit a cigarette and stared ahead of her.

“Pain, fear and humiliation was in my body,” she recalls. “Fear that it would happen again, and panic that I had contracted HIV because the policeman didn’t use a condom.”

The risk of contracting HIV from anal sex is about 18 times greater than with vaginal sex, 2010 research in the International Journal of Epidemiology shows.

Vidima wanted to cry. But then she thought of her seven-year-old son, who lived with his grandmother, and his unpaid school fees.

She finished smoking, walked to her spot and resumed work.

In the early hours of the morning she took a taxi to the flat that she shared with her cousin.

Vidima ran a bath and washed herself as thoroughly as possible.

She remembers hearing the “normal early morning city sounds” of wailing police vehicle sirens.

When she got into bed, next to her cousin and her cousin’s baby, the tears started to flow.

But silently.

“I didn’t tell anyone about the rape,” she says. “What was I going to say?”

* Not her real name

This article was amended on 28 October 2019. The Amsterdam sex worker’s real name was changed to a pseudonym. She gave consent for us to use her name and pictures in July 2018, but withdrew consent in October 2019 after she had made changes to her life.

Mia Malan is the founder and editor-in-chief of Bhekisisa. She has worked in newsrooms in Johannesburg, Nairobi and Washington, DC, winning more than 30 awards for her radio, print and television work.