- Africa’s reliance on imports and donated vaccines has exposed how vulnerable the continent is, resulting in slow COVID-19 vaccine roll-outs.

- A handful of African countries are working to change the continent’s access to jabs through boosting vaccine production.

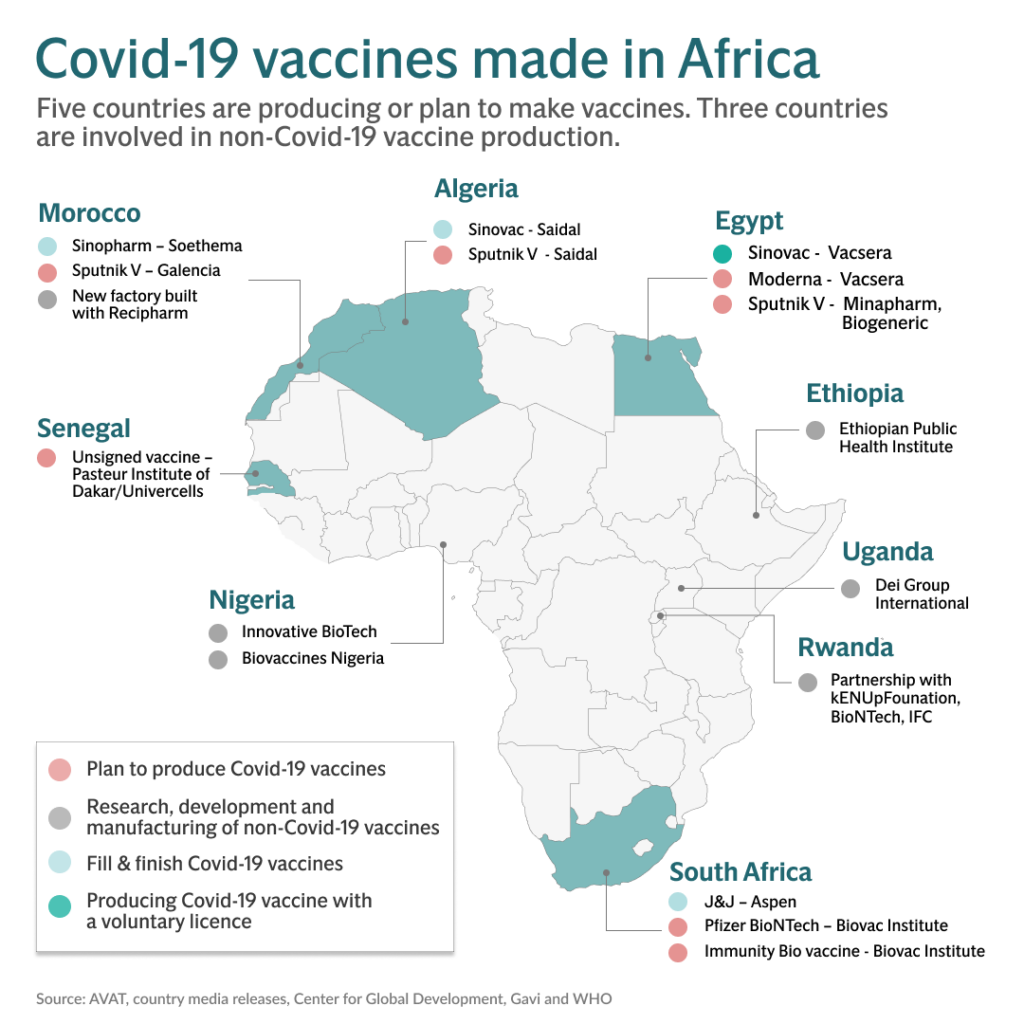

- African nations manufacture only 1% of the vaccines used on the continent. With local manufacturing, the African Union plans to push that figure to 60% in the next 20 years.

Long dependent on the world’s wealthy nations for its vaccine supplies, Africa is building up its own vaccine manufacturing capacity.

The continent’s life-threatening reliance on imports and donated vaccines has been laid bare by the pandemic, with a painfully slow and stuttering roll-out of COVID-19 jabs.

But that’s set to change, with South Africa, Morocco and Rwanda among several African countries forging ahead with the technology and infrastructure to manufacture vaccines.

The need to play catch-up in this pandemic and to boost resilience against future outbreaks of infectious diseases has catalysed efforts to boost Africa’s homegrown vaccine production.

“Relying on the West is not sustainable. Africa will always be at the back of the queue when it comes to accessing vaccines,” says University of Cape Town senior researcher for the Vaccines for Africa Initiative, Benjamin Kagina.

“COVID made the African continent realise that they are left behind and the only way they can stop that is by working together.”

Currently only a handful of African countries manufacture vaccines and few are involved with COVID-19 shots. Most of those carry out the end-stage production process known as “fill and finish”, where the product is processed, put into vials and shipped. Only Egypt is producing a COVID-19 vaccine from scratch.

New “fill and finish” facilities for COVID vaccines are being built in Morocco and Rwanda. Other existing “fill and finish” manufacturing plants in Egypt and South Africa are being repurposed for COVID-19 vaccines.

South Africa and Algeria are the only African countries that have announced plans to produce the pharmaceutical ingredients to make COVID-19 vaccines from scratch.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has hired South African start-up Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines to reverse engineer an mRNA vaccine against COVID as close as possible to the version produced by drugmaker Moderna, whose vaccine formula has not been shared.

Most of these manufacturing plants will start producing vaccines between early 2022 and 2023, working towards the African Union’s goal of boosting vaccine production on the continent from 1% of its vaccine requirements to 60% in the next two decades.

A lack of investment has kept African countries from producing jabs

The first vaccines were produced in Africa in the 19th century, with Vacsera in Egypt producing its first anti-venoms in 1881. This year, the same company became the second manufacturer of COVID-19 vaccines on African soil.

But a lack of investment has held back vaccine development on the continent, says University of Cape Town professor Ed Rybicki, the director of its Biopharming Research Unit.

“Africa basically has not put anything like the resources needed into vaccine production as a continent … to do anything more than ‘fill and finish’, as that is the ‘easy’ part of the operation. This includes the nations with the two biggest GDPs on the continent: Nigeria and South Africa,” he says.

One of the hurdles is pharmaceutical licensing. There are three kinds of license agreements: “fill and finish”, voluntary and compulsory licenses, the Health Justice Initiative (HJI), a South African non-profit organisation, explains.

“Fill and finish”, the most common license to be granted to African manufacturers, allows a company only to package a pharmaceutical product into different containers or devices.

A compulsory license allows a drug manufacturer permission to develop a vaccine at an affordable price in a country, while a voluntary license is a contract between the creator of the vaccine and manufacturers that offer technology transfer allowing them to make either a licensed or generic version of a vaccine.

Fatima Hassan, founder and director at the HJI, said, “the current system of exporting vaccines and relying only on ‘fill and finish’ licenses for this pandemic is not workable and leads to inequity on a grand scale, that is immoral”.

One solution to this would be ratification of the TRIPS waiver which is currently under discussion at the World Trade Organisation. But it’s a year since South African and Indian delegations tabled a proposal to temporarily waive intellectual property protections governing COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics.

During that time more than three quarters of the over 7-billion vaccines administered worldwide have gone into the arms of people in wealthy countries – and the life-saving proposal remains stalled.

So for now, “fill and finish”, or drug product manufacturing, is the only viable way for most African countries to start producing vaccines.

“If you start at the very beginning (of developing vaccines) initially, it costs more. It demands more in terms of training and workforce development. And it takes longer,” explains Africa Vaccine Manufacturers Initiative (Avmi) executive director Patrick Tippoo.

“So if you start with drug products, you get to the market quicker. You start making money quicker, which can pay for the investments that you will have incurred.”

Africa should have a say in how — and by whom — its vaccines are supplied

The experience of the Covax initiative – which promised fair access to COVID-19 vaccines for every country worldwide – highlights the need for African nations to quickly ramp up their own production and to have a say in how its vaccines are supplied.

Covax deliveries to Africa slowed to a trickle in May after India blocked exports by the Serum Institute to battle its own devastating outbreak. Since late June, with donations from the USA and Europe, supplies to Africa are ramping up again.

Internationally funded Gavi, the vaccine alliance, created a public market for the purchase of vaccines for Covax and shifted vaccine production to India, said African Union special envoy for COVID-19, Strive Masiyiwa, in an International Finance Corporation panel discussion in October.

“The buyer (vaccine alliance Gavi) decided that Africa’s vaccines would come from India. This was a strategic decision in which Africans had no say. But we find ourselves in this situation whereby when we got into a crisis – and India was in the same crisis – India said it would take care of its own people, and we went to the back of the queue,” said Masiyiwa.

How can Africa stop this from happening again? While it may be too late for this pandemic, the continent is taking steps to increase manufacturing capabilities and facilitate the development of vaccines for emerging diseases, such as Ebola, Lassa fever and Rift Valley fever.

The aim is to build capacity to manufacture 30 to 60% of needed vaccines for future pandemics and 20 to 60% of vaccines for routine immunisations, according to a report on COVID-19 by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

“The continent must now seize new opportunities to fast-track further development and to accelerate regulatory processes,” said Gavi in an emailed comment. “If countries can prioritise these measures, local production in Africa will become an essential part of how we prepare for the next pandemic.”

Vaccine production in Southern Africa

South Africa is the only country producing vaccines in Southern Africa. There are two “fill and finish” factories, Biovac in Cape Town and Aspen in Gqeberha.

Only the Aspen facility is producing the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccines at the moment, which is being shipped to countries on the continent and in the Caribbean through the Africa Vaccination Acquisition Trust.

Shauneen Beukes, Aspen’s communications manager said, “Aspen has invested some R3-billion in the sterile manufacturing facility in Gqeberha in the Eastern Cape.”

Biovac, a state-partnered pharmaceutical company that supplies an assortment of vaccines, plans to produce the two-dose Pfizer BioNTech vaccine from the second half of 2022.

The goal is to manufacture 100-million doses a year for the African market using raw materials from Europe using a “fill and finish” license.

Biovac also signed an agreement with US-based Immunity Bio, of which South African-born surgeon and billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong is the chairman. This will allow Biovac to manufacture a COVID-19 vaccine being developed by Immunity Bio, which is currently in clinical trials.

There are also discussions with Johnson & Johnson to evaluate the further expansion of capacity at the Eastern Cape site in South Africa to enable increased COVID-19 vaccine production, including a possible license for Africa.

The WHO’s tie-up with South Africa’s Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines is part of a $100-million plan to make a vaccine against COVID-19 close to the Moderna version. Once Afrigen’s scientists have cracked the code to produce the vaccine on a mass scale, the WHO plans to pay the firm to teach others how to do it.

Vaccine production in East Africa

In East Africa, Rwanda has received funding to develop an mRNA plant with BioNTech, the kENUP Foundation and the International Finance Corporation. The facility will be built in Kigali.

The financing for the project will include end-to-end mRNA vaccine production and a “fill and finish” vaccination manufacturing plant.

Along with Senegal and South Africa, Rwanda is also on the shortlist for US drugmaker Moderna’s planned mRNA COVID-19 vaccine factory.

Uganda started building an mRNA vaccine manufacturing plant in July, funded by Uganda’s Dei Group International. It should be finished in about four years, but it is not intended to produce COVID-19 vaccines.

Vaccine production in North Africa

Algeria, Egypt and Morocco produce COVID-19 vaccines that they are exporting or plan to export to the rest of the continent.

Egypt began producing a coronavirus vaccine using a ”fill and finish” licence. The state-owned Vacsera company produced its first batch of one million doses of Vacsera-Sinovac serum in July, using raw materials shipped from China and has since begun making the vaccines from scratch.

The company will begin to export vaccines to the rest of the continent from November.

Two other Egyptian companies, Minapharm and BioGeneric Pharma, have entered a partnership with the Russian Direct Investment Fund to produce Sputnik vaccines.

- READ MORE: The verdict is in — and Sputnik V is out

In September Algerian pharmaceutical company Saidal started bottling China’s Sinovac vaccine. They aim to produce five million vaccine doses per month by January 2022 and to export vaccines to the rest of Africa.

The same pharmaceutical company also signed an agreement to produce Russia’s Sputnik V, with production scheduled to start at the end of 2021.

Morocco has signed an agreement with China to make Sinopharm for the continent using a “fill and finish” licence. The country will start producing vaccines for export in December. Pharmaceutical company Sothema estimates that it will produce 5-million Sinopharm doses a month.

And last November, Morocco’s Galencia signed an agreement to produce Sputnik V.

Vaccine production in West Africa

Senegal is in the process of building capacity to “fill and finish” a yet-to-be announced COVID-19 vaccine with Belgium biotech group Univercells and the Pasteur Institute of Dakar.

In October, Moderna announced its plans to build a vaccine facility in Africa with Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa as the main contenders. The pharmaceutical company aims to produce 500-million vaccine doses annually through this facility.

This story is part of the Vaccine for the World series from the Evening Standard in London.