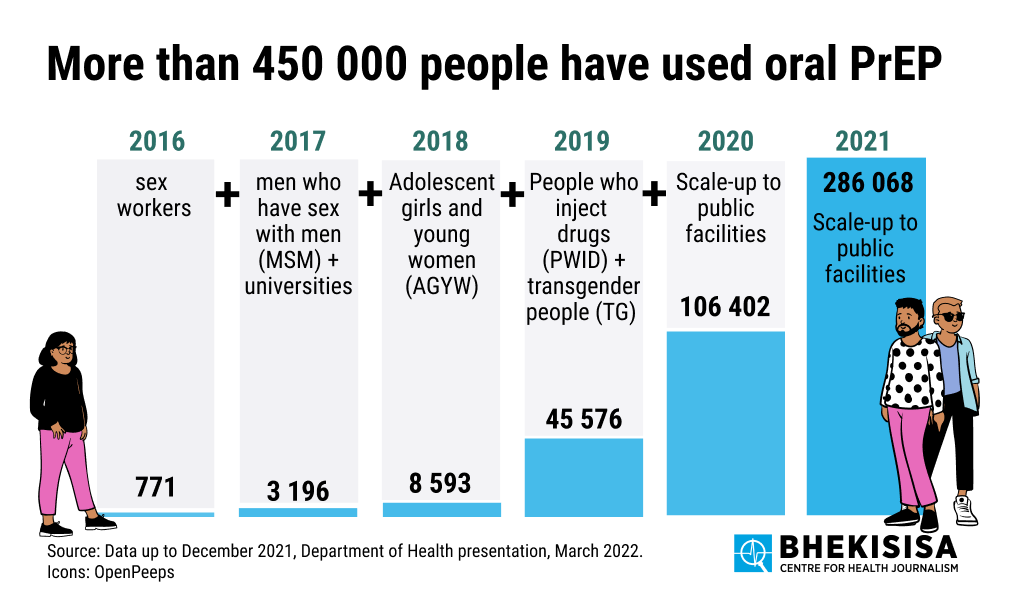

- The annual number of public healthcare patients who use the HIV prevention pill, Truvada, has increased from 771 to over 250 000 between 2016 and 2021. In 2020, the government made it available to everyone using government clinics. Before the policy change, the medicine was only available to specific groups who have a high risk of contracting HIV, for instance, sex workers, men who have sex with men and university students.

- The health department’s latest data shows that more than 450 000 people received the HIV prevention pill between 2016 and 2021 from state facilities across the country.

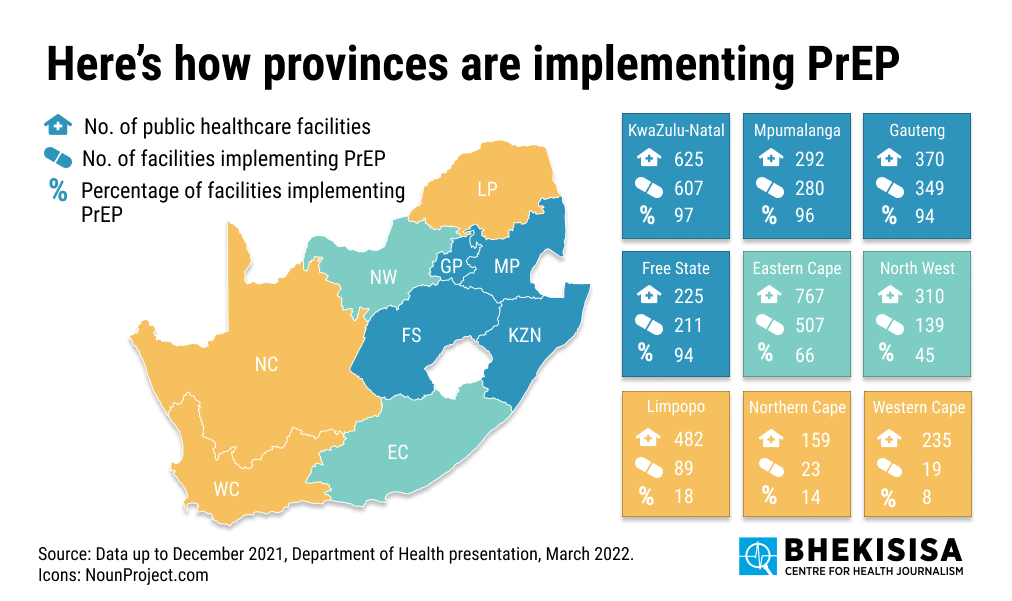

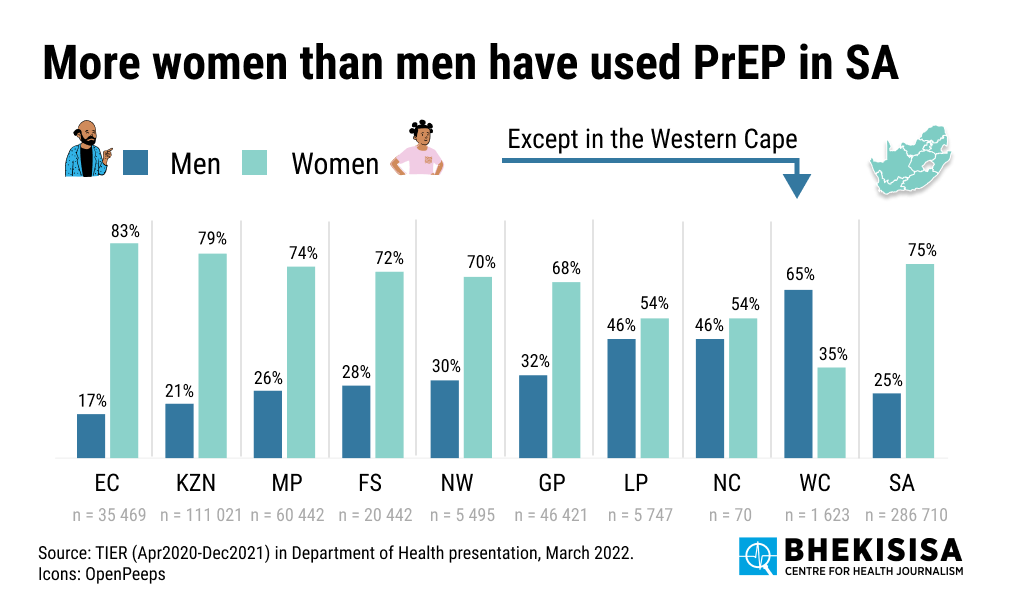

- KwaZulu-Natal’s state facilities are in the lead when it comes to stocking HIV prevention tablets (97% of them do) and the Western Cape is last in line at 8%. But, the home of the Mother City is the only province in which men use HIV prevention medicine more than women.

Twenty years ago, there was very little you could do to prevent yourself from getting infected with HIV, other than to not have sex or use condoms each time you had sex. Today, the situation is very different because researchers have made great progress with something known as biomedical interventions. In easy speak, these are things such as pills, injections or vaginal rings that you can use to lower your chances of contracting HIV if you have sex without a condom.

Scientists call these types of interventions pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, because you use them before you’re exposed to HIV and they then help to prevent you from getting infected with the virus (prophylaxis is preventive treatment). PrEP for HIV contains antiretroviral drugs (the same medicine that doctors use to treat people infected with HIV) that shields your immune system’s cells from getting infected with HIV.

So can you get PrEP in South Africa?

Right now, you can only get a pill that you need to take daily for it to work well (the pill is also called oral PrEP). The tablet needs to be in your system for at least 30 days before you get exposed to HIV and, if you take it correctly, it can reduce your chances of contracting the virus though sex by between 92 and 98%. Alternatively, two pills can be taken before sex and a third a day after sex (such a person would obviously need to know when they’re going to have sex). But this method, called “prep on demand” is mostly only recommended for men who have sex with men because studies showed when people take the pill in this way it doesn’t work as well during vaginal sex as it does for anal sex.

There’s also a silicone ring that women can insert into their vaginas, called the dapivirine vaginal ring. It can reduce a user’s chances of contracting HIV via sex by 27%. The ring was approved for use by our medicines regulator, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (Sahpra), in March, but the national health department says it is still in the process of developing user guidelines and negotiating prices with the manufacturer, so the ring is not yet available.

The PrEP method that research shows works best, is an HIV injection called cabotegravir that you take every two months. The jab virtually wipes out someone’s chances of contracting HIV through sex. One of the reasons scientists think a cabotegravir injection works better than a daily pill is because it’s so much easier to adhere to; some people struggle to remember to take a pill each day, and the less often you take it the less well it works.

Cabotegravir only recently came onto the market and is not yet approved for use by Sahpra, although the injection’s manufacturer, ViiV Healthcare, has applied for approval. But even if the shot is approved, it’s likely to be unaffordable: it sells for R54 000 an injection in the United States. Compare that with the R90 a month the health department says a supply of HIV prevention tablets costs for one person (R60 for the actual pills and R30 for administration costs such as nurses’ salaries, blood tests, etc).

[WATCH] Tap, fire, PrEP: Check out the little blue pill that’s been missing from your Grindr game

Experts say ViiV Healthcare would need to sell cabotegravir to the health department for no more than R180 an injection (so for about the same price as a month’s supply of pills) to make it viable to be rolled out in the public health sector. Eight out of ten people in South Africa are reliant on government clinics and hospitals, so this is where the injection would be needed most.

But why does South Africa need PrEP?

Because the country has 200 000 new HIV infections per year (about 550 per day) and pills, vaginal rings and injections can help to lower this figure dramatically.

At a recent Twitter Spaces Bhekisisa event, Linda-Gail Bekker, the director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the University of Cape Town, said: “We need fast PrEP, like fast food. PrEP should be available at many points, in many ways. PrEP is not a luxury in this country, our HIV burden makes it a top priority.”

So where is South Africa at with the roll-out of HIV prevention pills in the public health sector? We asked the health department for the latest figures (they gave us the numbers up until the end of December 2021), made infographics and asked the department questions about some of the statistics.

Find the figures, as provided by the health department, here.

1. How many people have received HIV prevention pills from a government facility?

A total of 450 606 public healthcare users in South Africa have been given HIV prevention pills.

How did this happen?

The country started to make the pill available at government health facilities in mid-2016. But the tablet was phased in, so only certain groups of people could initially get it. In 2016, only sex workers qualified for oral PrEP from state clinics and hospitals — in that year, only 771 sex workers used the pill. In 2017, men who have sex with men and university students were added to the list of people who could get the medication; the number of people using oral PrEP increased fourfold in that year to 3 196. In 2018, when teen girls and young women were phased in, more than twice as many people — 8 593 — as in 2017, took the pill. In 2019, 45 576 people started to take the tablet (people who inject drugs and transgender people were included that year). In 2020, anyone who needed oral PrEP, as long as a health worker prescribed it and the pills were stocked by a facility, could get the pills from government facilities (106 402 people used it) and in 2021 that number more than doubled to 286 068.

The health department has not yet released figures for 2022.

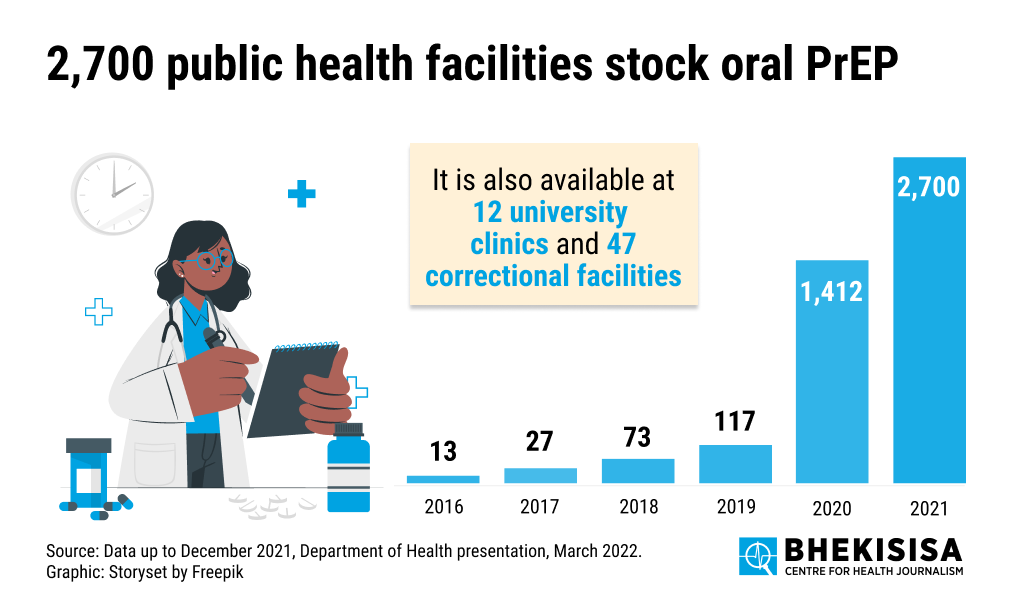

2. How many government clinics and hospitals stock HIV prevention pills?

Two thousand seven hundred (63%) of the 4 263 public health facilities in South Africa stock HIV prevention pills (2 224 of the facilities that make the pills available are primary healthcare facilities, in other words clinics where people go first before seeking more specialised care). In addition to that, 12 university clinics and 47 clinics at prisons also supply the tablets.

How has this increased over the years?

In 2016, only 13 hospitals and clinics stocked oral PrEP (these were pilot projects). In 2017, this had more than doubled to 27 facilities, in 2018 to 73 and in 2019 to 117. When the pill was made available to everyone in 2020, the number of facilities increased 12-fold to 1 412 and in 2021 these had almost doubled to 2 700.

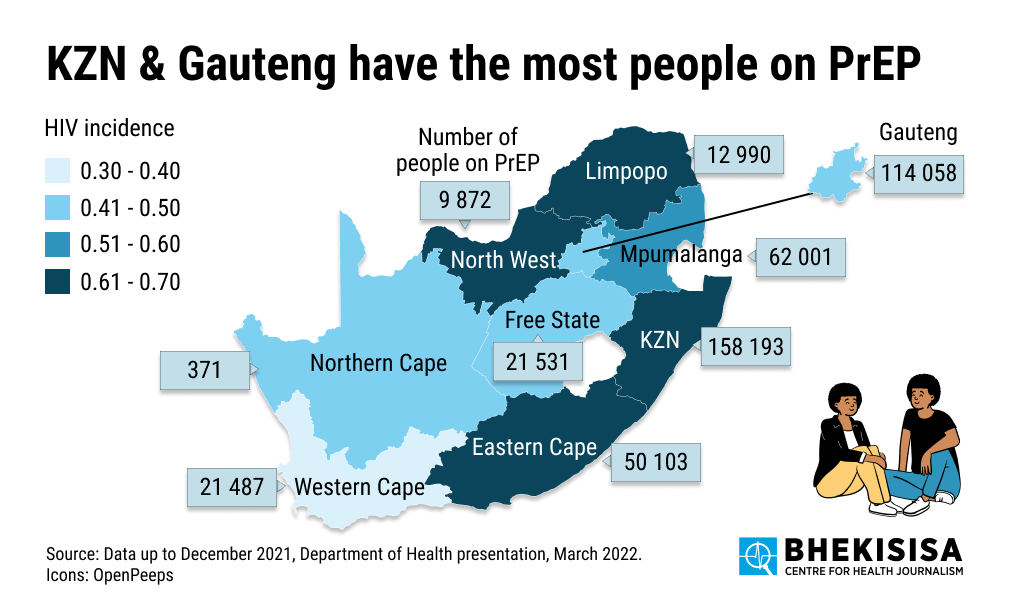

3. Which provinces use the most HIV prevention pills?

KwaZulu-Natal (158 193) has the most people on oral PrEP (reminder: this figure only includes people who got the pills from government hospitals and clinics) and Gauteng (115 058) the second most. Gauteng, however, has a larger population (15 176 115) than Kwazulu-Natal (11 289 086), so when we look at the proportion of the population covered, KwaZulu-Natal has almost double the percentage (1.4%) of people on oral PrEP than Gauteng (0.8%).

This distribution is, however, in line with the proportion of people infected with HIV in each province: The percentage of infected people in Kwazulu-Natal (18.2%) is higher than in Gauteng (13%).

Coverage in other provinces looks as follows:

Mpumalanga: 62 001 (1.4%)

Eastern Cape: 50 103 (0.8%)

Free State: 21 531 (0.8%)

Western Cape: 21 487 (0.3%)

Limpopo: 12 990 (0.2%)

Northwest: 9 872 (0.3%)

Northern Cape: 371 (0.03%)

Why is the coverage in the Northern Cape (0.03%) so much lower than in other provinces? The national health department says “the scale up of PrEP in this province was slower than in other provinces” because the Northern Cape didn’t receive money from donors to “accelerate PrEP delivery”, while all the other provinces did.

4. What percentage of state primary healthcare facilities in provinces stock oral PrEP?

The health department says it has a total of 3 465 primary healthcare facilities — 2 224 (64%) of these facilities stock HIV prevention pills.

KwaZulu-Natal fares the best: 97% of primary healthcare facilities keep oral PrEP at hand, followed by:

Mpumalanga (96%)

Gauteng (94%)

Free State (94%)

Eastern Cape (66%)

Northwest (45%)

Limpopo (18%)

Northern Cape (14%)

Western Cape (8%)

5. Which age group uses PrEP the most (if they get it from a government facility)?

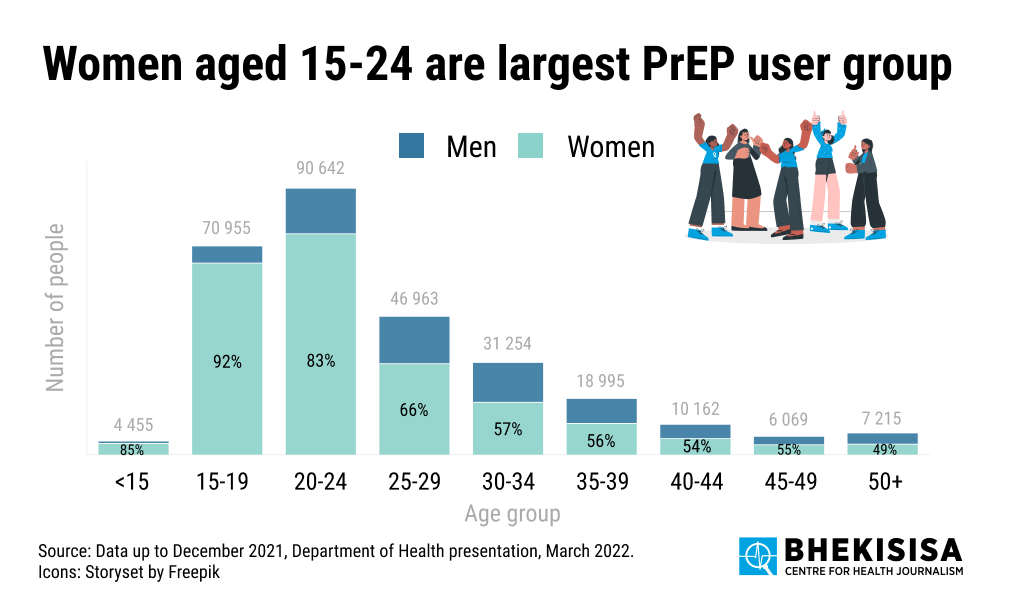

People between 20 and 24 years of age (90,642) have accessed HIV prevention pills via public clinics and hospitals the most, followed by those in the 15 to 19 year old group (70,955). That works out to 1.5% of the 15-19 year group using oral PrEP accessed via government clinics (the 15-19 population is 4 793 213, according to the district health information system statistics that the national health department uses) and 1.9% of the 20-24 year old population (there are 4,824,133 people in this group).

The older people get, the lower the uptake of the tablets is. This is in line with sexual behaviours — young people tend to take more sexual risks than older people. HIV prevention pills aren’t meant to be used permanently, rather during periods of your life when you’re more likely to have sex without condoms with risky partners, which in return increases your chances of contracting HIV.

In each age group, except in the case of people who are 50 years and older, more women than men use HIV prevention tablets. This is especially pronounced in the younger age groups (15-34 years).

South Africa’s HIV infection figures show that teen girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 24 get infected with HIV at a much faster rate than their male peers, as well as both older men and women. The national health department says that “there is increased demand creation and social mobilisation to reach this age group with HIV prevention interventions such as PrEP”, which is why the uptake of the pills for women between 15-24 is so much higher.

6. What is the gender breakdown of uptake of pills in provinces?

In each province, the uptake of HIV prevention pills is significantly higher among women than men, except for the Western Cape. The health department says the reason why the scenario looks different in the Western Cape could be because of preference. Thato Mtshaba, the director for HIV prevention, says: “It’s not because men are offered PrEP more regularly than women in the Western Cape, it could just be because there is more preference among men. But we’d need to analyse the data in more detail to know for sure.”

7. Want to get an HIV prevention pill for free in Johannesburg?

Here is a list of government clinics that offer oral PrEP: