Follow the country’s health minister’s journey from trainee doctor to his current role leading the fight against the coronavirus pandemic in this feature from our archives.

It was mid morning when the young doctor noticed the tiny girl on a wooden bench in the labour ward, slumped and sobbing.

She was 13, but was only a few inches taller than the hospital table next to her.

Terror flashed through her eyes.

Outside, on a green hill overlooking the Msunduzi river in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, chattering gogos were selling oily amagwinya (vetkoek) and cooldrinks to patients and families who had braved rugged terrain through the early morning hours to reach the health facility.

But the girl with the tear-stained face was alone.

The hospital, Edendale, was about 10 kms outside Pietermaritzburg, in uMgungundlovu district.

“What’s the problem?” the doctor asked the youngster, kneeling beside her.

She pointed at a protruding tummy that hid her thighs and whispered: “It’s very sore. It’s been like that for a while now.”

The physician paused and asked: “Are you pregnant?”

Then the girl, slowly shaking her head from side to side, replied: “I don’t know…”

Zweli Mkhize crosses one leg over the other as he sits on a large, black boardroom chair on the top floor of the Durban International Conference centre. It’s a Tuesday evening in June, just 12 days after he replaced Aaron Motsoaledi as the country’s health minister.

Earlier that day he had opened the 9th South African Aids conference and stated: “Between yourselves and the government, we are bound to actively defeat the spread of HIV.”

But tonight, the chanting of protesting HIV activists fighting to end drug stock-outs and for better clinics is seeping into the boardroom from the exhibition area below.

Advocates armed with various causes have been demonstrating fiercely throughout the day.

There are almost eight-million people infected with HIV in South Africa, according to health department figures; only about 60% of them are on treatment.

The group that is becoming infected with HIV by far the fastest is teenagers and young women between the ages of 15-24, studies have shown.

And, although Health System Trust data shows this figure has decreased over the past five years, close to 7% of women giving birth in public health facilities are younger than 18. Three quarters of such pregnancies are unintended, a 2012 household survey published in the journal African Health Sciences found.

Mkhize takes a deep breath and explains: “That girl [in Edendale Hospital] had no idea that she was having labour pains, because she didn’t know she was pregnant and had no one to ask if she was. She received no antenatal care.”

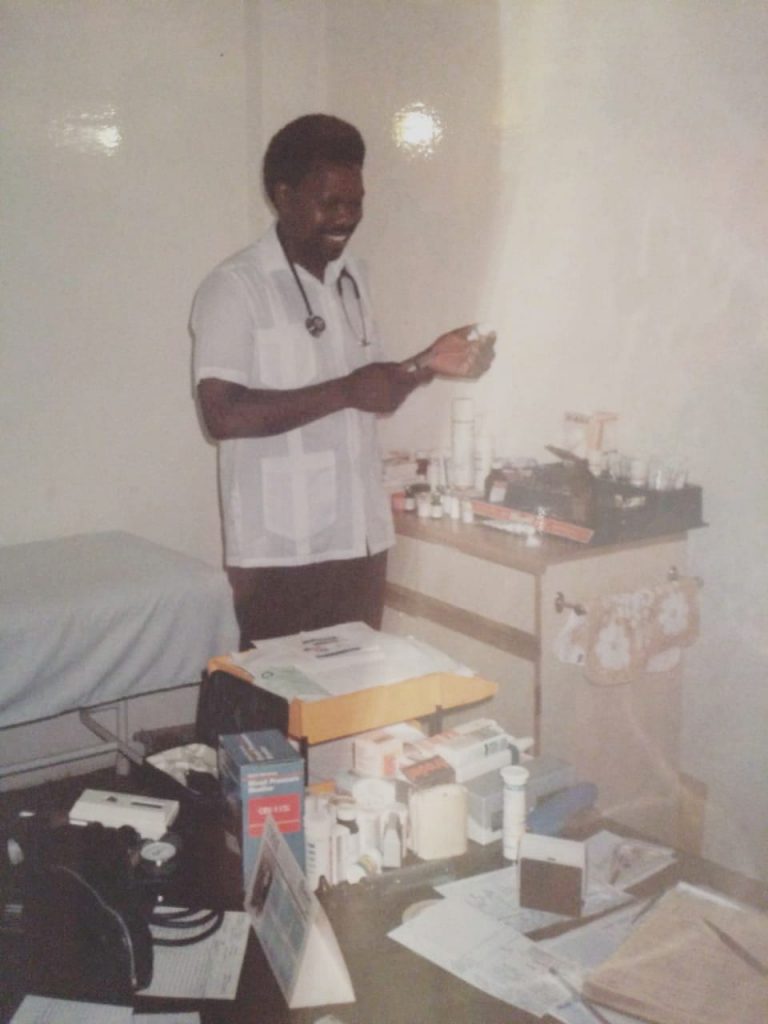

The teenager was one of Mkhize’s patients when he worked as a physician at the hospital in 1986, four years after he had graduated as a medical doctor from the University of Natal.

The African Health Sciences survey, which was conducted in the Eastern Cape, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga, revealed that 55.5% of female respondents between 18 and 24 got pregnant the first time because they didn’t understand the risks involved in what they were doing or didn’t know how pregnancy happens.

The minister sips lukewarm water from a boardroom glass.

“I had to perform a cesarean section on her and a healthy baby came out,” he says. “But it always hits me: somewhere along the line, a lot of the health challenges we face, including HIV and Aids, have got more to do with the breakdown of families than the individuals you meet in health institutions.”

Mkhize continues: “In a normal family you would expect there to be a mother who will talk to her daughter and explain ‘this is going to happen to your body and so on’. But that pattern of mentorship has been disrupted.

“The problems you encounter in hospitals and clinics are not just outcomes. They’re indicators — of how broken society is, how well our economy is and how well the country’s governed.”

Thirty-three years have passed since Mkhize helped his young patient to bring her baby into the world.

Eighteen years after the incident, South Africa became a democracy. Subsequently, the country has had four presidents. State capture by means of a labyrinth of patronage networks has plundered the public purse to the tune of at least R1.4-trillion. The country’s main electricity provider has all but collapsed, sending the economy into freefall. And the official unemployment rate is approaching 30% with GDP growth having plummeted from 3.5% in 2011 to 0.6% in 2019.

But, during this time, the government also passed one of the continent’s most progressive termination-of-pregnancy laws, and expanded the public health system’s HIV treatment programme from non-existent to the world’s largest. The availability of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), which keep people with HIV alive, has led to the country’s institutional maternal mortality rate (women dying while giving birth in public health facilities or soon thereafter) declining by almost a third over the past decade, and life expectancy has increased from 57.7 years in 2013 to 64 in 2017.

Mkhize himself had active roles in all of the above: But parts that saw him cast as both hero and villain.

In 1994, at the age of 38, he became KwaZulu-Natal’s first, and the country’s longest-serving, health MEC, his tenure lasting until 2004. Mkhize’s command of the health sector of the province with the highest HIV infection rate in South Africa overlapped with one of the most tragic chapters in the nation’s history: Thabo Mbeki’s HIV denialism that saw the president vehemently opposed to making HIV treatment available, because of unfounded beliefs that ARVs were poisonous. Hundreds of thousands, many of them in KwaZulu-Natal, died as a result.

But the young MEC had the courage to defy Mbeki and to permit at least some of the province’s public health clinics to put HIV-positive patients on ARVs. By April 2004, when the state began to provide free HIV treatment, there were already 11 000 patients in KZN on the drugs, according to Mkhize’s CV.

However, as an influential member of the ANC’s provincial executive (he was ANC chairperson in Kwazulu-Natal from 2008 – 2013 and treasurer between 1994 and 1997), and a member of the party’s national executive committee (he became a member in 1990), Mkhize — at least publicly — also toed dangerous political lines.

He formally opposed a court case of the HIV lobby group, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), that fought for access to treatment that could help prevent HIV-infected pregnant women from transmitting the virus to their babies. Many, including the then TAC activist Nathan Geffen, who’s now editor of the donor-funded news service GroundUp, believe this was because Mkhize “could not bring himself to break ranks with Mbeki publicly”.

And, when Mkhize advanced to the rank of KwaZulu-Natal premier in 2009, he did not (again, at least publicly) oppose his then Health MEC Sibongiseni Dlhomo when the provincial minister bought tens of thousands of potentially harmful non-surgical medical male circumcision devices known as Tara KLamps. Altough studies had shown that medical circumcision could reduce a man’s chances of contracting HIV through vaginal sex by about 60%, there were serious concerns about the Tara KLamp: it hadn’t received World Health Organisation approval, research showed that men who used it experienced bleeding and injuries to their penises, and, perhaps most importantly, the contraptions had been procured without a tender from a businessman who had strong links to Zulu king Goodwill Zwelithini, who received an expensive car from the merchant around the time the devices were purchased.

It’s been clear long before Mkhize became health minister that the quality of healthcare that someone’s able to access in South Africa is largely dependent on how much the person is able to pay for it. And in a country as starkly unequal as South Africa, and given the current state of the public health system, that means that most people don’t get good healthcare.

Cue the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, in the making for the past eight years, that Mkhize released in August. In so doing he achieved his desire to do so within the first 100 days of his reign.

Mkhize is correct when he says South Africa’s [health] indicators reflect how broken society is, how well our economy is and how well the country’s governed — and uMgungundlovu isn’t doing well.

If the health minister’s 1986 patient and her baby are still alive, they’d be 46 and 33 respectively.

In 2012 uMgungundlovu became an NHI pilot site, thus receiving huge amounts of additional funding to improve health services there and to prepare the area for the implementation of the scheme.

But, despite the extra money, if the mother and child have remained in uMgungundlovu, not much has changed for them: they’d be living in the district with the highest percentage — 29.7% — of adults with HIV in South Africa, according to a study published in the journal Nature in May.

The chances that either of them would have completed high school, the district municipality’s demographic data shows, are less than one out of three. Would they have jobs? Not likely; the country’s 2011 Census revealed only about a third of people in uMgungundlovu are employed. In fact, the district health department’s health plan states, 15% of people here survive on less than R400 a month.

And, if the now 33-year-old child was a girl, the possibility that she too would have given birth to a baby as a teenager is high: The Health System Trust’s District Health Barometer (DHS) reveals that 15% of women giving birth in the district’s public health facilities are between the ages of 10 and 19, and only about half of women between the ages of 15 and 49 use a modern form of contraception.

Her likelihood of dying during pregnancy or while giving birth in a public health facility would have been significantly higher than that of the average woman in South Africa: in uMgungundlovu, 170.6 out of every 100 000 live births result in the death of a mother compared to the national average of 105.7, DHS data shows.

But perhaps the most crucial health statistic to highlight in the district, after the release of the NHI Bill, which aims to get wealthier South Africans to subsidise the healthcare of the poor, is: according to its health plan, 85% of uMgungundlovu’s population have no form of health insurance; they’re solely reliant on an underfunded, dilapidated public health system.

[WATCH] Health minister Zweli Mkhize on why South Africa needs an NHI

The shockwaves struck two days after the NHI Bill, which spelt the end of medical aids as we know it, and the introduction of a massive state-run fund, was released.

The JSE healthcare index lost more than 6%; Discovery, which administers South Africa’s largest open medical scheme, saw an 11% decline in its shares, and the pharmaceutical company Aspen’s shares fell by 12%.

The Bill, which the health department’s performance plan says should be approved by the national assembly and the national council of provinces by the end of next year, and enacted by the president by 2021, would effectively force the 16% of the country able to afford medical aid premiums, to use the NHI’s services or to pay out of pocket for care — because medical schemes will only be able to offer top-off services.

Instead, an NHI fund would buy the same health services for everyone, regardless of their income. In this way, the Bill argues, uMgungundlovu’s uninsured population will receive healthcare on the same level as wealthier people, simultaneously being subsidised by the contributions of the ‘rich’ 16% who will be compelled to contribute “mandatory prepayment” to the Fund.

Back in the boardroom, Mkhize swivels in his chair.

“The NHI is about financing, about the procurement of services. Those two ultimately have to shift from where we are right now,” he says. “We don’t have a choice.”

But there are serious gaps in the Bill that the health minister would have to address if he wants the country’s buy-in. The question many ask, is: is he equipped — and willing — to do this?

In the light of the past month’s substantial criticism, also from those who support the principle of social solidarity that the NHI is built on, Mkhize will require the ability to consult — and act on input.

A common concern is that there has been a serious lack of consultation in the drafting of the Bill; despite hundreds of submissions for the 2018 iteration of the document, the 2019 version contains few changes based on such proposals. For instance, despite civil society’s apprehension about the immense power rendered to the health minister in the 2018 copy, the 2019 Bill assigns the minister even more control.

“The word “independent” is removed from the description of the Board of the Fund and it is rendered accountable to the minister, rather than to parliament,” Sasha Stevenson, the head of the health rights programme at the social justice organisation Section27, writes in an op-ed for Spotlight. “[The board] is appointed by the minister rather than by parliament [and] the minister may remove members of the Board or dissolve the Board. [Moreover], the minister, rather than the Board itself, also now appoints the Board chairperson.”

But, if Mkhize’s inaugural budget vote speech in July is anything to go by, the minister could be a better listener than most in the cabinet. The speech went through seven drafts as he circulated the contents to civil society for input. He’s also got strong links with the Progressive Healthcare Forum, a group of more than 250 influential nurses, doctors, academics and public health officials, many who he’s known for decades, dating back to their roles as anti-apartheid activists. The Forum lobbied for the Presidential Health Summit and the consequent social compact that was released in June.

Mkhize says: “For me, civil society is a very important player in this issue. But the key issue is, can we partner with civil society in helping to monitor the effectiveness of health services in such a way that we use their views and feedback to actually correct the management style?”

Simultaneously, however, according to Nathan Geffen, Mkhize’s lack of consultation about the Tara KLamp in 2010 resulted in an intense civil society campaign against the then KZN premier and his government to warn men against it and to convince the province to pull the clamps.

Geffen remembers meeting Mkhize in Pietermaritzburg to discuss the matter: “We saw a disturbing side to him,” he recalls. “He entered the room and then spoke for 1 hour 20 minutes of the next 1 hour 35 minutes before leaving. This seemed to be a tactic to avoid having to answer difficult questions.

“He told us the matter had received more publicity than it warranted, that the Treatment Action Campaign’s response was disproportionate, and that no one had died. He said he was suspicious of our motives.”

[WATCH] Health Minister Zweli Mkhize on the role he wants civil society to play in the health system

Mkhize is a politically powerful man. Influential enough, according to Section27’s former head, Mark Heywood, to do “exactly what [former Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi] couldn’t do” : he’s got the political authority within the ANC to ‘crack the whip on health MECs, to phone premiers and say, ‘sort your shit out’”.

The law, as it stands at the moment, doesn’t give the health minister the legal power to supervise health MECs; they report to their respective premiers. The only way a national minister can tell his or her provincial counterparts what to do, is through strong political connections with premiers, which according to ANC insiders, Motsoaledi largely did not have.

The NHI Bill wants to override at least part of this reporting structure: hospitals and clinics will report to the NHI, and not provinces, and they will also get paid directly by the Fund. The reaction to this from the DA, which runs its own health system in the Western Cape, is a threat to haul Mkhize to the Constitutional Court for usurping the powers of provinces.

But they’re up against a man with considerable influence.

Mkhize occupied one of the ANC’s most powerful positions, that of treasurer-general, between 2012 and 2017, which made him part of the party’s top six leadership. At the end of his tenure he was nominated as deputy ANC president, but turned it down in exchange for “unity”. His move opened the position up for David Mabuza at the party’s 2017 December annual conference, which resulted in Cyril Ramaphosa being elected president.

In May, political analyst Ralph Mathekga told Bhekisisa: “Mkhize is Ramaphosa’s close ally, similar to what Gwede Mantashe [the ANC’s national chairperson and minister of mineral resources and energy] is to the president.”

Ramaphosa is a staunch proponent of the NHI, branding its detractors and challengers “opponents of transformation”.

But, given Mkhize’s history and standing in the ruling party, will he be able to put public health above his own political interests when it comes to the NHI? Will he move decisively against those in the ANC who may act improperly within the context of the NHI, even if it means losing significant political support? In other words, will he replicate his behaviour in dispensing ARVs in KwaZulu-Natal, against Mbeki’s policies?

Several critics have warned that a centralised cash chest, such as the NHI Fund, over which a single minister has an extreme amount of power, recalibrates state capture-like systems and structures that could open paths to the money being hijacked, in the same way that so many political leaders have done over the past decade.

Health sector players want to know: Will Mkhize fight to ensure this doesn’t happen? And: does he himself have a record of clean financial governance?

Worryingly, it has twice been alleged this year that he used his authority to either raise money for the ANC, or to facilitate loans for the Public Investment Corporation (PIC). The claims have yet to be tested in court, and Mkhize has strongly denied them.

Shortly after he became health minister, the former head of the PIC, Dan Matjila, accused Mkhize of using his political influence to pressure Matjila into asking organisations that had been funded by the PIC to contribute towards the cost of ANC political events in 2016. Also, the Sunday Times earlier this year published allegations that Mkhize received kickbacks to the tune of R4.5m for facilitating a loan to an oil company from the PIC in the same year.

Yet Mkhize has a good record as KwaZulu-Natal’s Finance and Economic Development MEC between 2004 and 2009, a period during which he implemented successful austerity measures that saved the province from overspending. And as Premier he improved the number of municipalities in KwaZulu-Natal that received clean audits consistently.

Mkhize has strategically appointed Nicholas Crisp as developer of the NHI Fund. Crisp, a medical doctor who headed the Limpopo health department in the 1990s, has a proven history of successfully combating corruption and financial mismanagement.

In a recent interview with Stephen Grootes on SAFM, Crisp estimated the current cost of corruption in the national and provincial health departments at “far more than R20 billion per year”. He wasn’t just pulling a figure out of the sky. He has previously intensively researched the financial price of losses to fraud and dodgy deals in the health sector.

Crisp’s number of R20 billion is shocking; it’s almost half the national health department’s 2019/20 budget of R51.46 billion.

Crisp, the authors of the Presidential Health Summit Compact and the NHI’s critics agree on one thing: that the health department doesn’t possess nearly enough capacity to confront the challenge of achieving good financial management in the health sector.

That’s why, as the Compact notes, there’s such a grave need for establishing a unit in the health department to work closely with the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) “to prevent and address corruption and wastage in the health sector both at national and provincial levels”.

According to the Compact’s timeline, this unit needs to be up and running by December 2020.

But analysts say the NHI needs more than that. The Bill needs to include independent accountability mechanisms such as allowing Treasury to act as a final accounting authority, and to make provision for civil society or private sector oversight.

And what will be needed, in terms of money and resources, to implement the scheme that the state says must be functional by 2026? Mkhize responds: “It will still not be adequate to say the amount that we’re currently spending on health in the public sector and the one that we’re spending on the private sector, that the sum total of the two, is enough to run the NHI. I think we need more.

But what I want to discourage is a suggestion that there should be a reason why the NHI should not be introduced. I think nothing should stand between us and the NHI — not even the cost.”

Treasury says it will soon release a cost estimate.

[WATCH] Health Minister Zweli Mkhize says the human cost of not having an NHI is larger than the financial cost

Back in uMgungundlovu the Msunduzi river flows just like it did 33 years ago, albeit with much higher levels of pollution. Now, like then, gogos sell their amagwinya to patients in front of Edendale Hospital. Now, like then, family structures in the area are broken.

Will the NHI change anything for this community?

In seven years’ time, will Mkhize’s teenage patient and her baby, now older and probably more sickly if they remained in the district, be able to go to a local health facility and get treatment for diabetes or cancer, without having to line up for eight hours, or getting to the front of the queue only to be told that the drugs they need are out of stock, or the radiation machines are broken?

Mia Malan is the founder and editor-in-chief of Bhekisisa. She has worked in newsrooms in Johannesburg, Nairobi and Washington, DC, winning more than 30 awards for her radio, print and television work.