- Pharmacy expert Andy Gray has spent a big chunk of his career writing treatment guidelines and essential medicines lists for our public health system.

- Gray’s daily listserv, called Druginfo, has become a staple for many health experts. He told our reporter, Sean Christie: “It has become a bit obsessive. If that listserv falls over, I’m like, the world is not normal.”

- Get to know Gray, the “insider’s insider” in South Africa’s drug policy world.

Finding Andrew Gray was not easy. We had planned to meet at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine off Berea’s Umbilo Road, but my phone died en route and the screen of the newish digital directory in the medical building gave me an Eskom-lobotomised blank stare. I pleadingly asked a well-groomed young man in turquoise scrubs if he knew Gray.

“He’s the pharmacist, isn’t he? Very highly regarded. Follow me,” he said, and we walked together into the Main building, arriving outside a double door below the words THERAPEUTICS AND MEDICINES MANAGEMENT.

I rang the doorbell, and waited, and after some minutes went all along the floor knocking on doors until eventually (it was a Friday afternoon) I found some humans in the faculty’s call centre. I explained my predicament and in hushed tones the manager said, “we never see anyone going in or out of there”.

Andrew Gray did, however, come out of those doors after his number was called — a tall, good-looking man with a snowy, close-cropped beard and an impressive head of white hair.

When I mentioned the call centre manager’s Hitchcockian comment he let out an explosive laugh. “It’s true, there are only five of us, and we all teach on so many other campuses that it can be difficult to find a pulse.”

The insider’s insider and his listserv

I had located the physical man but knew just enough about Gray to suspect that pinning him down as a subject might be more complicated.

In matters of drug policy, Gray is the insider’s insider.

Specifically, he authors a daily email digest of news on medicines and healthcare policy called Druginfo, which combines information from a comprehensive range of regulatory bodies, medical journals and news outlets. The newsletter is curated for a local healthcare audience with such intuition and dedication (Gray often includes a personal commentary on news items) that one feels a warm, almost familial gratitude, well conveyed by the fact that people who have never met the man, myself included, refer to him as Andy.

“It has become a bit obsessive. If that listserv falls over, I’m like, the world is not normal,” he says.

Most would sleep soundly contributing this much in a day but Gray does it before breakfast, literally.

“It costs me about an hour before work starts. Over the years I have gotten to know the information sites really well, and it takes seconds to know if there’s something new in a major regulator’s website, or in a major newspaper.”

“Hang on, don’t just talk, come and do it”

Gray spends much of his time working as a senior lecturer in the division of pharmacology but to call him an academic would be misleading, as a typical day includes participation in the meetings of a wide array of institutional committees and boards. He is a member, for example, of the national essential medicines list committee, several South African Health Products Regulatory Authority committees, and a span of World Health Organisation panels and groups, including the Expert Panel on Drug Policies and Management and the Guideline Steering Group for Family Planning.

“I suppose I like to have my fingers in the pie. I dislike sitting on the outside, commenting only,” he says.

The pathways by which Gray has arrived at such influence are not linear, but his approach has always been straightforward.

“I find that if you stick your nose into a thing somebody inevitably goes, ‘hang on, don’t just talk, come and do it,’” he says.

Gray’s unabridged curriculum vitae is 36 pages long, and bears out the adage often attributed to Franklin Roosevelt, that if you want something done, ask a busy person.

Where would he fix himself on the spectrum of workaholism, I ask?

“Ag,” he exhales (like it isn’t the first time he has been asked this), “I think there’s something about academia that means you never shut the till. I do struggle to take a whole weekend off.”

How did Gray choose pharmacy?

A CV does not tell you much about a man but one detail, right at the top of Gray’s, drew my eye.

NAME: Andrew Lofts Gray (formerly Andrew Johan Rauch — name changed in 1985)

“Johan Rauch was my father’s name,” Gray explains. “My parents divorced when I was six and I didn’t see my father much after that, so I took my mother’s surname and my grandfather’s middle name, and made it official in 1985.”

Gray was born in 1959 in Worcester in the Western Cape but moved with his mother and brother to the Eastern Cape in 1965, originally to a farm that her parents were managing in the Cathcart district. His mother then took up a teaching post at Queens College in Queenstown, and this enabled Gray to attend Queen’s until he matriculated.

“It is one of those classic English, boys-only, mostly-boarding schools,” he says, praising the school for giving him “an incredibly strong base”.

Gray was torn between social sciences and the sciences — he studied English, history and Latin, maths, chemistry and physics — and considered studying law but ultimately committed to pharmacy. His decision was informed in no small way by the many childhood hours he had spent hanging out in Mager & March (now Magers), the Queenstown pharmacy founded in the 1880s by William Mager.

“There has been a Mr Mager in charge ever since. Mike Mager was in charge when I was growing up and he was an absolute inspiration — he was this man in white, the guy who allowed me to fiddle around in the storeroom and restock my chemistry set,” says Gray.

When Andy met Rosemary

Four years of undergraduate study at the pharmacy school at Rhodes University would give Gray more than a degree — in Grahamstown (now Makhanda) he studied alongside and fell in love with his Zambian-born classmate Rosemary Burrows. “After graduating, we interned at pharmacies right here in Umbilo,” he says. A photo of Andy and Rosemary from their 1984 wedding in Eiffel Flats, Zimbabwe, sits on Gray’s desk. Taking it in his hand, Gray says with a hint of a smile, “I developed this myself.” The story is illuminating, both for what it reveals of Gray’s move into clinical research and his DIY approach to life in general.

“As an intern I came to know some of the lecturers at the medical school, which was then part of the University of Natal. One was a larger-than-life American immunologist called Steve Gaffen, who asked me if I would like to join his lab and do my master’s,” Gray says. Gaffen was doing early work in immunology, using immunoglobulins (a protein that helps the body fight infection) to treat Gram-negative infections (infections caused by bacteria that are resistant to many drugs).

“He was using animal models,” says Gray, “and so for my master’s I looked at eye infections in rabbits. The research required me to photograph rabbit eyes, and so I asked the technicians in the physiology department, which had a darkroom, to teach me how to process photos.

”Military service beckoned after Gray finished his master’s in 1984 but rather than take up arms for the apartheid government he “did a duck to England, and worked as a barman in Chiswick, among other things”. When Gray and Burrows (now Mr and Mrs Gray) returned to South Africa in 1985, they both found jobs in hospital pharmacies — he in the pharmacy at King Edward VIII Hospital, then a 2 000-bed public sector teaching hospital located next to the University of Natal Medical School. Gray was ultimately conscripted. He served in the military’s medical services for two years, after which time he returned to work in the King Edward VIII pharmacy.

The mysterious appearance of journal subscriptions

Until 1994, all health services in South Africa’s public sector were provided separately to different ethnic groups and King Edward VIII Hospital was designated only for Black African and Indian patients. In a lecture Gray gave in 2015 after receiving the Donald E. Francke Medal (awarded to individuals who have made significant international contributions to public health pharmacy), he explained how his time in the hospital’s pharmacy forced a confrontation with a discriminatory system, characterised by “overcrowded and poorly equipped facilities, grossly inadequate staffing for the inpatient and outpatient load that was faced on a daily basis”.

“The pharmacy service was primitive. It was paper based, there was no intravenous admixture service and no therapeutic drug monitoring, but there was camaraderie and there was opportunity,” says Gray.

“We would get visiting clinicians coming in from other countries, and we would say to them, think of a disease, something that you’ve never seen — neurofibromatosis — and we are sure to have it. That’s an incredibly rich place to be. But you’re stuck at the bottom of Africa, under sanctions in the middle of the 1980s. So what can you do?”

Quite a lot, it turns out. With minimal resources, Gray and his colleagues, “expanded clinical pharmacy until King Edward became a very desirable place to join the pharmacy department”.

For Gray, the unlikely ties that connected King Edward to the front edges of pharmaceutical progress were two journal subscriptions that used to land in the hospital pharmacy every month, as if by magic: Drug Intelligence and Clinical Pharmacy, and the American Journal of Health Systems Pharmacy.

“To this day I have no idea who ordered them but when they arrived in the post you devoured the latest research and thought, ‘I can do this’. There’s something very special about working in an embattled context but being able to find a formula for assessing renal function in a paper in an old journal.

Activist? Gray takes the label as a compliment

Gray entered academia in 1993 but his time in hospital pharmacy had sparked a parallel journey in pharmacy politics — he went on to lead the South African Association of Hospital and Institutional Pharmacists at a time of “wholesale revision of the entire corpus of South African law.

“A hospital pharmacy leader was expected to be as comfortable discussing the basis for once-daily aminoglycoside [a drug that works against many types of bacteria] dosing as arguing about the implication of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. Everything had to change, everything was up for grabs and you could step up and tackle issues and change things,” says Gray, who gave workshops on medicines regulation for the Treatment Action Campaign, and as a member of the UNITAID Proposal Review Committee was involved in the decision to establish the Medicines Patent Pool, led by the access activist Ellen ‘t Hoen.

A former director general of the national health department once accused Gray of being an activist.

“I took that as a compliment,” says Gray.

“Much of my work has been about choosing the right medicines and writing the right guidelines so that people use them better. That immediately brings up the question of cost, and ‘how do we intervene to make these things more affordable?’”

The political weaknesses of pharmacy in SA

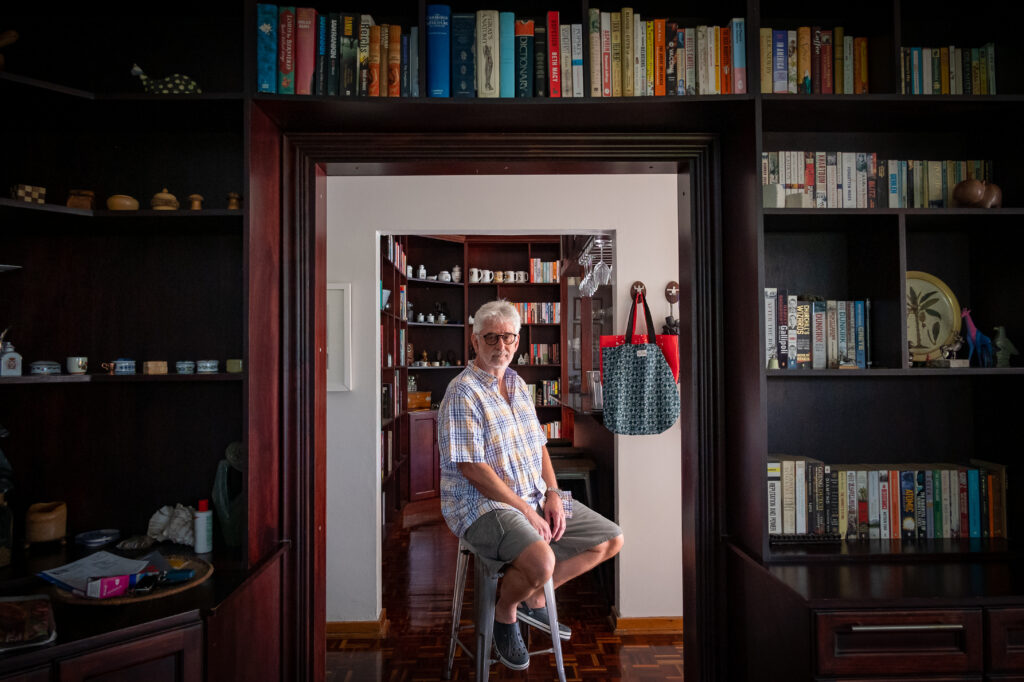

Our time is up but with much left to talk about Gray invites me to visit him the following morning at his home in Westville. As I move through the hilly suburbs west of Durban, passing gardens stuffed with flamboyants and tibouchinas, the scars of the 2022 mudslides are still faintly discernible under new grass.

“The flooding wasn’t such a problem for pharmacy but the 2021 unrest exposed a major political vulnerability,” Gray says, sitting on the stoep of a spacious but unpretentious home, overlooking a blue pool and a faux-rockface pump cover.

“When the Mooi River toll plaza (on the N3 between Durban and Johannesburg) turns into a burning wreck, pharmaceutical supply freezes, because almost everything in this country is moving by road and practically the entire pharmaceutical industry is located in Joburg,” he says, adding that the over-concentration of pharmacy on the Highveld echoes a far bigger pharmaceutical supply chain problem, “and that is over concentration of production, especially the production of the active ingredients, in China and India, especially for off patent, older molecules, such as the penicillin’s”.

One of the items Gray posted on Druginfo was a link to a Health Policy Watch article citing a British Medical Journal study revealing that, to reverse the trend of pharmaceutical offshoring, the United States government invested nearly $31.9-billion (R584.8-billion) in mRNA technology alone.

“If you convert that into Rands, it’s our entire economy, so we can’t make that sort of investment,” says Gray, who believes there is a contradiction in South Africa’s national drug policy. “We say we would like to boost our local production and reduce prices. Now, somewhere along the line those objectives are going to clash.

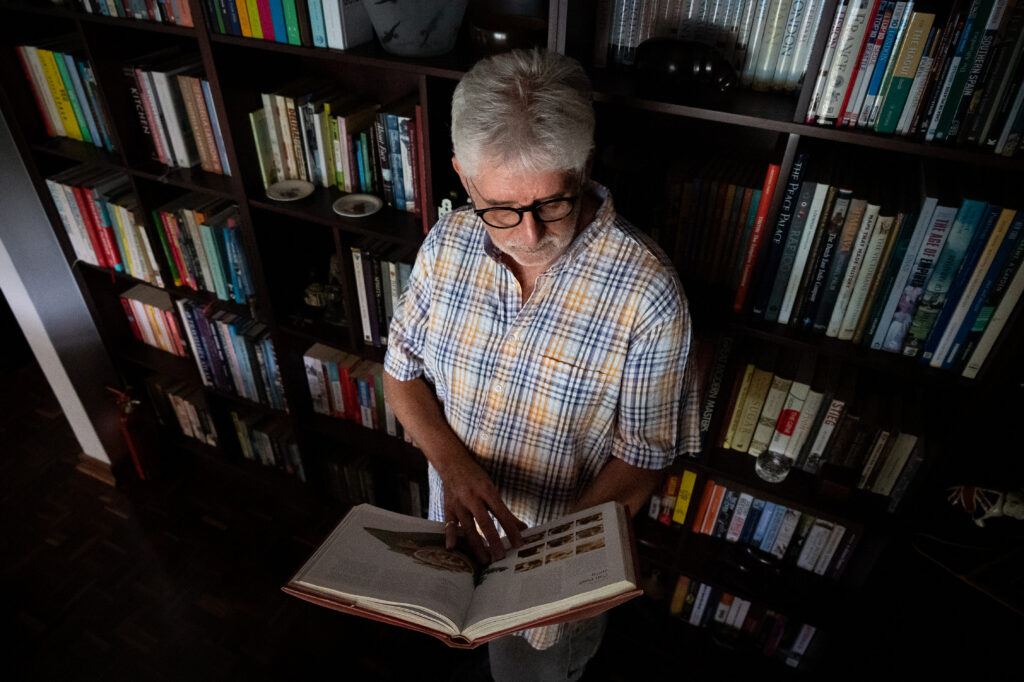

What’s on Andy Gray’s bookshelf?

Gray’s geopolitical fluency is impressive, and much of the work underpinning it lies behind us, in the neat bookshelves in the living room and bar, organised by theme. In the international history section I spotted Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul: Memories and the City, and Anthony Beevor’s Stalingrad. In the South African section, Mark Heywood’s Get up, Stand Up and, somewhat off theme, a biography of Bennie Osler, the Springbok great.

“My grandfather was a provincial lock forward, and at school captained the first team in which Bennie Osler was a rising star,” Gray explains, admitting that he reads “like crazy”.

“If I have any attribute that’s a bit special then it’s the fact that I can usually remember where I read something, be it a fact of political history or some legal detail,” he says.

The walls not covered in shelves disclose his other philia: travel. I spot a caricature of Lisbon’s 28 tram, and a picture of Amsterdam’s Leidsegracht, interspersed with his mother’s watercolour paintings.

“I’ve been lucky that my work requires me to go abroad about a dozen times a year. This has enabled me to indulge a love of food, particularly,” Gray says, and recounts how, once in Chiang Mai, “a guy on a bicycle with a portable grill cooked and served some pork sausages that contained all the flavours of Thai food in one skin: the chilli, the garlic, the ginger, it was all there in every bite. I think that encapsulates a food experience that literally stops you dead in your tracks.”

Saturday serendipity

Rosemary Gray appears from the house, dressed for their Saturday lunch appointment — it is time to get going. Rosemary has had a stellar career of her own, and Andy, in parting, recognises the ways in which they have complemented each other’s practice.

“We’ve almost never been in the same field at the same time. When I was doing postgraduate training, Rosemary went to Addington Hospital and worked in the public sector. While I was moving into research, she ran a specialist, intravenous nutrition outsourcing service. Her experience makes me a more complete pharmacist,” he says, and Rosemary nods and quickly adds that the same applies to their elder daughter, who has followed her parents into pharmacy.

“Would you believe it, but Mike Mager’s granddaughter, Nicole, did her internship with my daughter Sarah. How’s that for completing the circle!” says Gray, beaming at the serendipity of it all.

Sean Christie is a freelance journalist and author.