Rising temperatures linked to outbreaks of dengue fever high in the Kathmandu Valley, experts say.

Lilawati Awasthi is used to the risks that come from living in a remote mountainous district in the far west of Nepal. Floods, landslides and treacherous roads are a part of daily life. But this year she faced a new hazard: mosquitoes carrying a mystery illness.

When she began to feel sick in September she was not overly concerned at first. “I thought it was a simple fever, but it wouldn’t go away,” says the 50 year old. “We went to the hospital and it turned out I was suffering from dengue.”

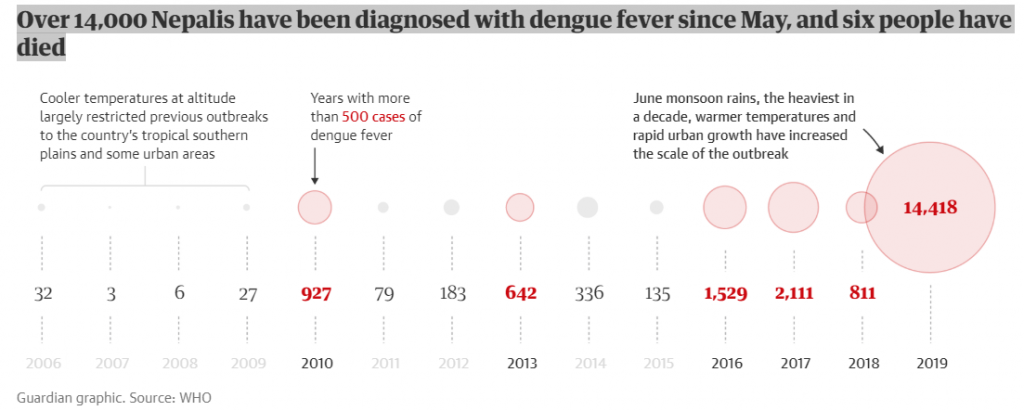

Awasthi is one of more than 14 000 Nepalis who have been diagnosed with dengue fever since May, in an unprecedented outbreak that has left health professionals and the government reeling.

Some experts believe the actual number of infections to be closer to 140 000. Six people have died.

Dengue, a mosquito-borne viral infection with symptoms similar to severe flu, first appeared in Nepal in 2004. Minor outbreaks have occurred periodically, largely restricted to the country’s tropical southern plains and some urban areas.

This year’s outbreak has been remarkable both in its scale and reach. Dengue has been found in 67 of Nepal’s 77 districts, including those at higher elevations, a trend experts say is linked to the climate crisis.

A hot mess: The link between Dengue and climate change

“The role of climate change in poor countries where the health system is not robust is very big,” says Meghnath Dhimal, chief research officer at the Nepal Health Research Council. “There has been a rapid geographical expansion of dengue, especially from the lowland to the highland.”

Almost 2,000 cases have been recorded in the Kathmandu Valley, which at 1,400 metres sits higher than Britain’s tallest peak, Ben Nevis.

A combination of factors are behind this year’s outbreak: prolonged and heavy monsoon rains and rising temperatures, alongside rapid urbanisation and population movement.

Road expansion has created opportunities for the virus to move to higher altitudes, spread by infected people and mosquitoes carried in vehicles.

Once mosquitoes reach higher elevations where they would normally perish, rising temperatures enable them to survive, says Dhimal. “We have found that mosquitoes are now able to establish a population at up to 2 000 metres.”

Awasthi is the first person to contract dengue in her village, says her husband, Ram Dutta. “It really worries me that new diseases like dengue are becoming common. This area is getting hotter each year. There used to be very few mosquitoes before, but they are becoming common these days.”

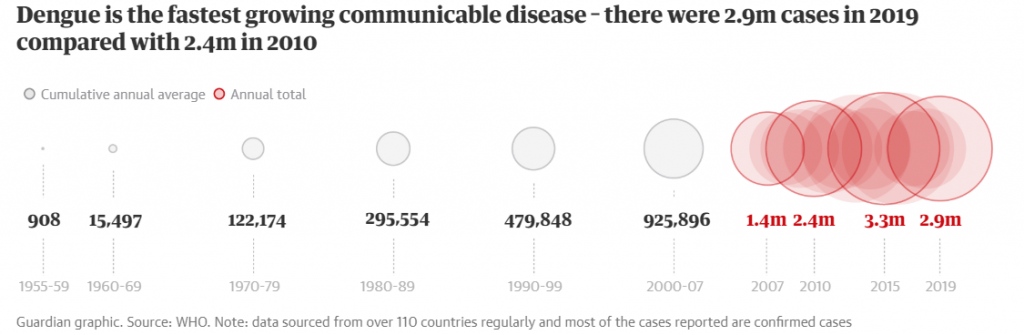

The growth of dengue in Nepal follows a global trend that has seen the number of infections grow rapidly to an estimated 390 million a year, according to the World Health Organisation. The UN body says about half the world’s population is now at risk.

At the Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease hospital in Kathmandu, the director, Basu Dev Pandey, is worried about the future. “It could be a disaster. During the peak of this year’s outbreak it was so difficult: 10,000 people came to the hospital. There was dengue-phobia.”

Pandey says the number of recorded cases in Nepal this year is a “gross underestimate” because the symptoms of dengue are similar to a typical fever. “Many people just visit the local pharmacy for treatment, and in Kathmandu the majority of patients go to private hospitals, whose data is not included in the government’s statistics.”

At the height of the outbreak, the hospital was overrun with patients. “People were lying on the ground all over the place. They just collapsed on the spot,” says Lal Bahadur Waiba, who works in the outpatient department. “The crowd was so big we had to open at 7am and set up stalls on the street outside.”

Waiba and 13 other hospital staff contracted dengue themselves. “You get headaches, pain in the back and joints, nausea. The pain is intolerable,” he says.

At the same time, mass migration to urban areas has resulted in overcrowded cities with poor infrastructure and haphazard waste management. A weak health system and a lack of public awareness combine to create conditions where dengue can thrive.

Without access to piped water, many urban dwellers get their water from communal pumps and store it in buckets indoors, which makes an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes.

“Even a discarded noodle packet can hold enough rainwater for the larvae to breed,” says Pandey.

A huge public awareness programme is needed, says Dhimal. “There may be a big outbreak in the future. The message is clear, we have to start right now.”

This feature was originally published as part of The Guardian’s Global Development project.