Editor’s note: On 13 March 2023, World Rugby announced that it has plans to lower the legal tackle height in community and school rugby in a bid to cut the number of head injuries players experience. The success of the change will be trialled in a global study that starts in May. The South African Rugby Union said it’s discussing the country’s possible participation in the study with member groups such as the South African Schools Rugby Association.

- A plagiarism scandal has rocked the sports world and cast fresh doubt over the influence of the industry in research on head injuries. It’s also stirred up old allegations that sporting bodies and prominent researchers have underplayed the risk sportspeople run of developing an incurable condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which has symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s disease.

- In May, The Concussion In Sports Group will release new guidelines on dealing with head injuries — the guidelines will inform safety rules.

- In the meantime, tackling rules in some types of rugby are already changing overseas. Find out what led to this decision, and what it could mean for the future of the sport.

Five counts of plagiarism, 10 retracted scientific papers and red flags about 74 more articles because of publication misconduct.

Those were the ingredients of a huge shake-up in sports science that led to allegations about scientists downplaying how dangerous head injuries are for professional athletes over time.

The man at the centre of it all is Paul McCrory. He served as the editor of the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM) between 2001 and 2008, a period during which he published many opinion pieces, commentaries and editorials — including views on whether a blow to the head should mean keeping an athlete off the field.

In one of the retracted pieces, from 2001, McCrory misquoted an extract from a 1952 article on concussion in sport, which he then used to argue that recommendations for when a player can return to sport are based on “an arbitrary exclusion period”.

The controversy dealt a blow to the reputation of the Concussion In Sports Group (CISG), which compiles best practice rules for dealing with head injuries in sport. McCrory is a founding member of this body and was lead author on their 2017 consensus statement (although the investigation into McCrory’s publication misconduct does not directly link to the group’s recommendations).

The CISG’s official views guide rules on how to spot and deal with concussions set by Fédération Internationale de Football Association (Fifa) and World Rugby.

McCrory resigned from the CISG in March 2022. He did not respond to Bhekisisa’s requests for comment.

Controversy, criticism and chronic brain injury

Jon Patricios, a South African sports medicine physician who co-leads the CISG’s scientific team, and who is the main author on the group’s newest consensus statement (to be released in May), says the claims made against McCrory haven’t affected the rigour with which the CISG considered its views when putting together the set of recommendations.

But there have been changes to the way the CISG is structured since the previous consensus statement was published in 2017 though. This was to ensure its review methods are robust and to address claims that sporting bodies have too much influence over the scientific process, as a group of 17 researchers and public health advocates wrote in a letter in the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics in 2021.

Ethics experts appointed to review the CISG’s processes flagged similar worries in an article published in the Journal of Medical Ethics on 3 March.

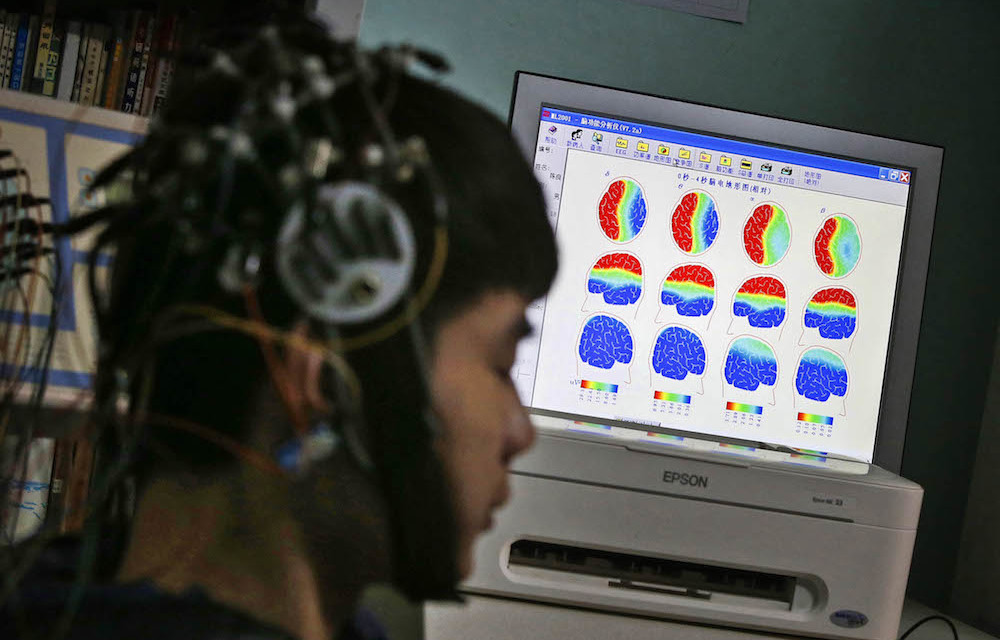

Another crucial criticism in the 2021 letter is that the CISG has consistently underplayed growing evidence that repeated hits to the head can lead to a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This is an untreatable neurodegenerative brain disorder, which means brain cells die or stop working, getting worse over time. Symptoms of this type of brain condition include memory loss, impaired judgement and personality changes such as violent behaviour.

However, there aren’t any tests for CTE other than examining brain tissue after death, so the condition can’t be diagnosed while someone is alive. In a case where a diagnosis of CTE is confirmed, a pathologist (a doctor who examines body tissues for signs of disease) would see an unusual build-up of a specific type of protein in the brain, which affects how well nerve cells work.

The CISG has been one of the main opponents of a causal link between repeated concussions and someone developing CTE, writing that “a cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and sport-related concussions or exposure to contact sports”. Yet major public health agencies such as the United States Centres for Disease Control and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Strokes acknowledge that CTE is “caused in part by repeated traumatic brain injuries” and the authors of the 2021 critique warned that the CISG’s 2017 statement is incomplete.

But in June last year, nine months after the 2021 open letter was published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, an influential study caused an upset. A group of researchers led by Chris Nowinksi of the Concussion Legacy Foundation concluded that repeated hits to the head do cause CTE.

We unpack what this could mean for players and the future of contact sports such as rugby and soccer.

How does CTE work?

In a healthy brain, so-called tau proteins help to keep the structure of nerve cells intact. But when there’s a build-up of these proteins in someone’s brain, they tangle together and prevent nerve cells from communicating with each other. This can affect a person’s ability to think and remember things, as often happens in Alzheimer’s disease or dementia.

Although hard blows to the head could lead to abnormal tau protein build-up, other factors — such as genetics — could also contribute. Scientists also caution that there is little conclusive evidence on how common CTE is, how many head impacts can lead to the disease and that the connection between what a brain looks like and how it functions is not clear.

“Not everyone, even with the worst forms of repetitive impact [such as boxing], develops a neurodegenerative disease. And that’s what makes the understanding quite murky,” says Anthony Figaji, who heads up paediatric neurosurgery at the University of Cape Town. He’s also the National Research Foundation’s chair on clinical neuroscience.

Plus, some of the symptoms of CTE, such as mood disorders (for example, depression), behavioural difficulties like suicidal thoughts or substance abuse, and impaired thinking or memory are commonly found in the general population, too.

What can the sports world expect from the new CISG consensus statement?

Meanwhile, a large group of current and former rugby players in the United Kingdom are suing international rugby regulators. They claim the organisations didn’t do enough to protect players from head injuries and concussions — and that they knew of the long-term risks to players’ health.

Among the group is the former captain of the Welsh national team, Ryan Jones. He told the British newspaper The Times in July that he was diagnosed with early-onset dementia and that his “world is falling apart”.

For the first time, the CISG will now include discussions on what kind of head injury is bad enough for a player to retire from collision sports such as rugby in their upcoming consensus statement, Patricios says.

The potential long-term effects, including CTE, is also one of 10 topics for which the group is reviewing new evidence, he explains.

More experts were brought in to evaluate research on the condition — including some of Nowinski’s co-authors — but Patricios wouldn’t say whether the Nowinski study was included in the CISG’s official review.

Regardless, Patricios explains: “Everybody who was involved in the CISG’s systematic review was aware of this paper. It’s played a significant role in our conversations.”

Why is the Nowinski study such a bombshell?

Nowinski and his team showed, from analysing more than a 100 studies, that the existing research on CTE meets all nine of Bradford Hill’s criteria for causation. This method is used in public health issues to help epidemiologists figure out if there’s a strong enough link between two occurrences to conclude that one thing directly leads to the other.

It’s a valuable method to use when there are environmental factors at play, the authors say.

Take cancer and smoking, for example. Many things could cause cancer, such as viruses or genetics. But by using Hill’s tests, researchers were able to show that smoking cigarettes causes lung cancer.

In the case of CTE, environmental factors would be collision sports such as rugby, soccer and ice hockey.

The Nowinski paper claims that the methodology that the CISG uses to evaluate evidence (called the Oxford Levels of Evidence) doesn’t catch environmental issues well enough because the method was designed for a clinical setting.

Hill’s approach has also been criticised, though, for being outdated, which brings into question whether it’s still a good way to make decisions in public health.

The Nowinski paper argues that diseases caused by environmental factors can be prevented, or made less dangerous. Their conclusion also poses a legal quagmire: children who participate in school sports are too young to consent to taking on the long-term risks of developing CTE.

But Figaji cautions that the study might not apply to the general population because it relied on brains that were donated to a brain bank for a specific medical reason (and thus are already more likely to have had signs of CTE), leading to a potential bias.

What does the new information about CTE say about the future of rugby?

The Nowinski study recommends rule changes around tackling and heading in children’s sports, as they are more prone to experiencing traumatic brain injuries. These include suggestions for limiting subconcussive blows (head bumps that don’t qualify as causing concussion) by, for example, banning heading the ball in youth football until the age of 14.

It also calls for players at professional levels to be told about the risk of CTE so that they can participate knowing what they sign up for.

But changing rules can be a prickly issue, as pushback from just under 79 000 people in an online petition showed when the English Rugby Football Union announced that from July, community rugby players will no longer be able to tackle people above their waist.

Patricios agrees that it would be important to educate people on the risk of CTE they may be taking on when they decide to play a sport like rugby, but he says it’s hard to help people make informed decisions without information about exactly how many head impacts would result in the condition.

He says: “Ultimately, people can still make the decision whether to participate or not.”

Here at home, the South African Rugby Union’s communications coordinator, Sindiswa Ximba, told Bhekisisa the Union is waiting for more data from research before it will change tackling rules.

Figaji says that until there is definitive research and ways to detect tau protein build-up that occurs exclusively in CTE, it could be too early to make big changes to sporting rules. However, being cautious, especially with children’s sport, is warranted “because there’s much we don’t know”. In general, he says, head injuries should be avoided. But what qualifies as an injury, even a mild one, remains unclear.

Figaji concludes: “At one extreme, we could be missing a situation where repetitive head impacts create a problem in the brain. On the other end of the extreme, we could be completely overcalling it if we haven’t directly connected findings [of potential protein build-up] with such a problem specifically.” – Additional reporting by Joan van Dyk.

Zano Kunene is a health journalist at Bhekisisa.