- Tests done on water taken downstream of a manhole from which sewage leaks into the Vaal River came back positive for cholera.

- South Africa’s drinking water is drawn from rivers like the Vaal, but it goes through a strict disinfection process to make it safe for human use.

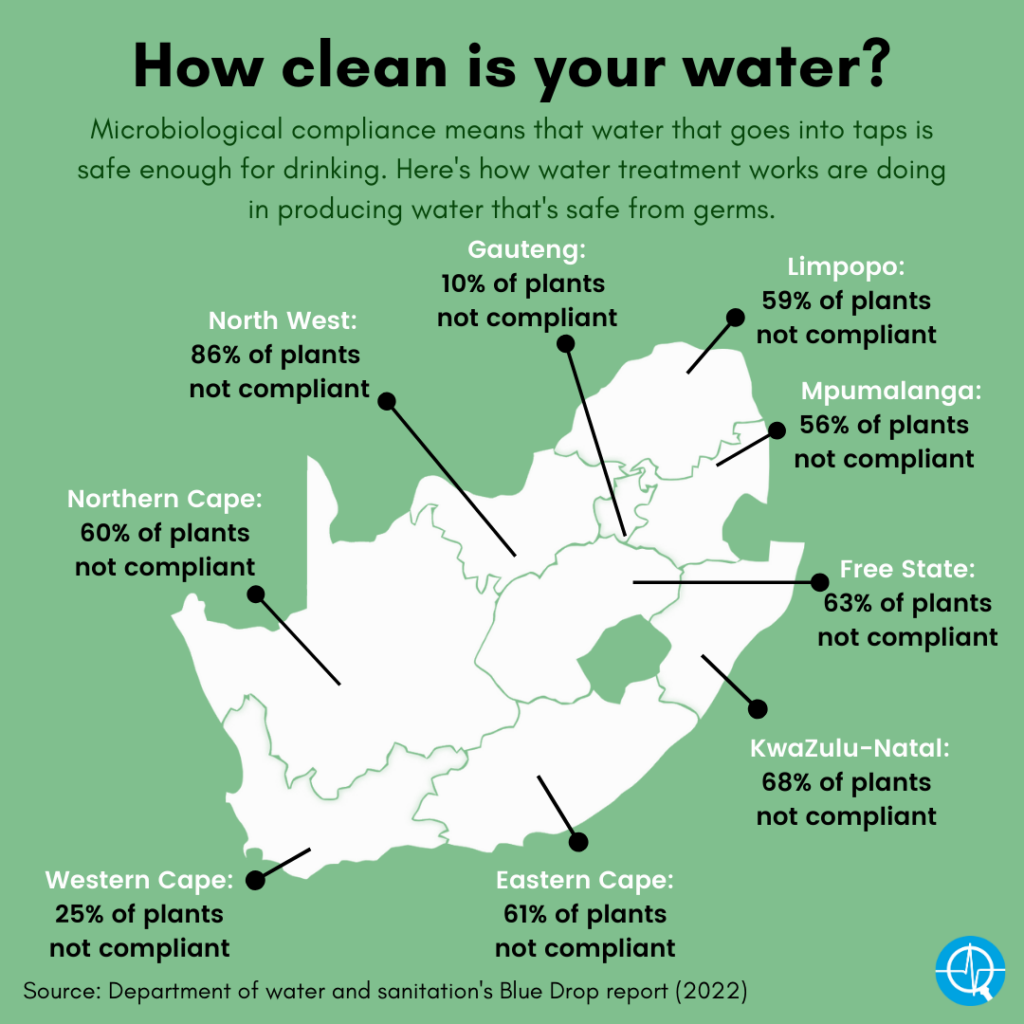

- But a report showed that in 2021, only 40% of the facilities in the country that disinfect water meet the standard for keeping water germ-free.

- Because these waterworks don’t treat and check their water to the legal standard, disease-causing bacteria (like cholera) could end up in tap water.

There’s cholera in the Vaal. But even though the risk of these bacteria making it to household taps is very low according to Benoît Le Roy of the South African Water Chamber, failing treatment systems and loadshedding may change this. The Water Chamber works with government organisations like Rand Water on implementing the national sanitation and water master plan.

The 2022 Blue Drop report, which gives an overview of the state of South Africa’s nearly 1 200 water supply systems, says that only four in ten of these can provide water that is unlikely to have germs that can make people sick.

In South Africa, water that is destined for household taps is treated to clean and disinfect it so that it’s safe to drink. But this requires a system that works around the clock and needs a steady power supply to keep pumps going — which is difficult when loadshedding can interrupt the process more than once a day, often for a total of up to eight hours.

Johannesburg’s water department confirmed that the latest tests done by Rand Water, which supplies 11-million people across Gauteng, the Free State, Mpumalanga and the North West with tap water, show that they have not found cholera in their reservoirs.

Cholera is a bacterial infection that causes runny stools, and in serious cases can lead to life-threatening dehydration. It spreads by drinking water or eating food contaminated with faeces from a person who is sick with cholera.

Rand Water’s announcement comes after lab tests on water downstream from a manhole leaking sewage into the Vaal River came back positive for cholera.

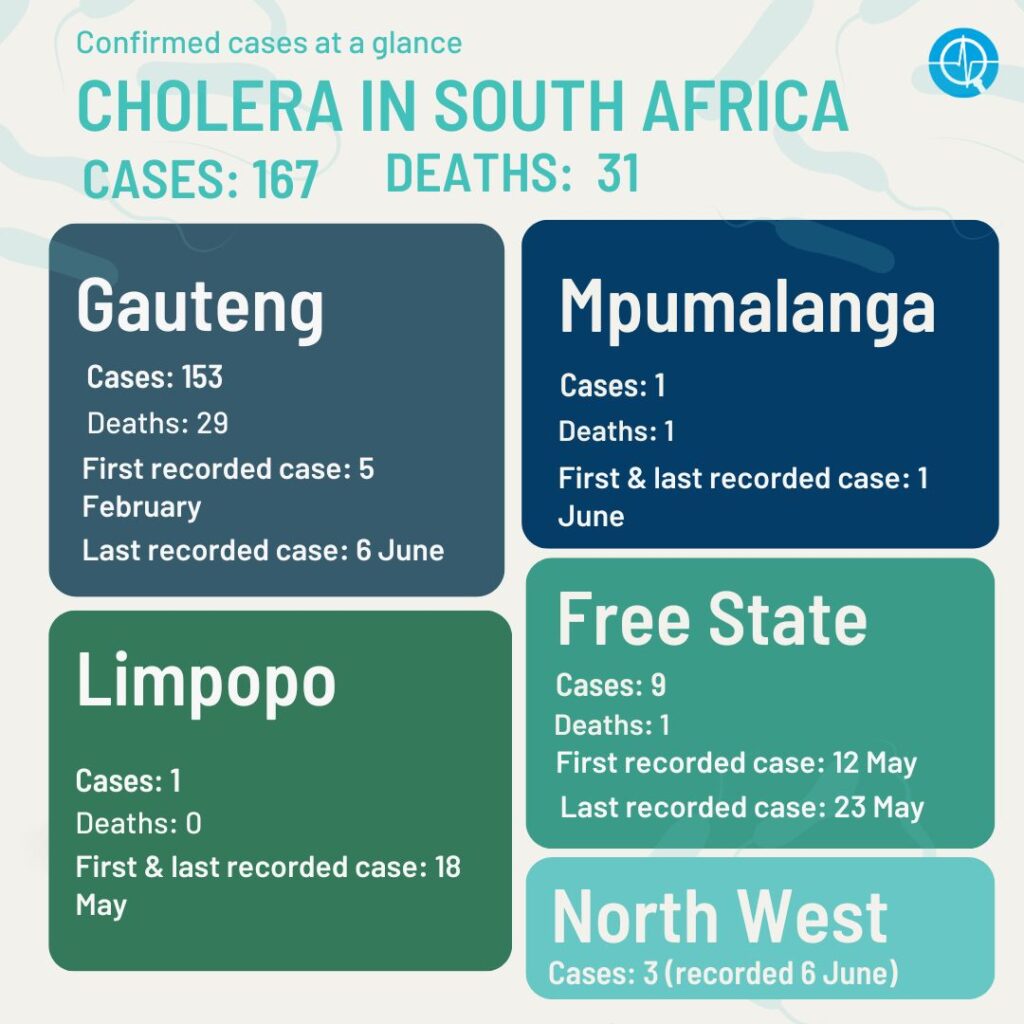

To date, 167 cases of cholera have been found in Gauteng, the Free State, Mpumalanga and Limpopo, with Tshwane in Gauteng the hotspot at 153 cases.

But while tests show that there’s no cholera in tap water at the moment, for how long will our water still be germ-free?

How water is cleaned

In January, the Breede Valley Municipality in the Western Cape asked residents to boil their tap water to make sure it was “absolutely safe” to drink as the systems that clean and disinfect the water run on electricity — and high stages of loadshedding could pose a risk of failure.

South Africa’s household water comes from rivers — and the used water from drains and toilets also goes back into rivers.

To make sure that our water is always safe for human use, there are two treatment systems in place.

The one is called a wastewater treatment plant. This is a town’s sewage works. Here water from municipal sewers flows into a series of open-air ponds where it is filtered, cleaned and disinfected step by step. Treated water — now called effluent — is then released back into a river and the sludge at the sewage works is dried so that it can be discarded. Effluent is tested to check that it does not contain toxic metals and chemicals before it gets discharged into a river.

[WATCH] How to diagnose & treat cholera: A guide for health workers

Water in rivers, including the treated wastewater, flows into dams, from where it’s drawn into another round of treatment before it can be pumped to a town’s water tanks. This is called water treatment works.

Again the water goes through a series of cleaning steps. Solids — from large objects like branches and leaves to smaller bits like gravel and sand — are first filtered out. The filtered water then goes into a set of ponds, where chemicals are added while the water is swirled around by large mixers. The chemicals make very small pieces of dirt that are still in the water clump together, which can then settle out.

Now carbon dioxide is bubbled through the water to lower the pH from about 10.5 to about 8, which is in line with international guidelines for drinking water.

pH is an indication of how alkaline or acidic a solution is. A pH of 7 is neutral. Values lower than 7 means a solution is acid-like, and above 7 the solution becomes alkaline, which means it can have a soapy feel.

Once the water has passed through another filter to remove any remaining sand granules, it is pumped into underground pipes that lead to booster stations where it gets disinfected with chlorine. As an extra fail-safe, two more rounds of disinfection follow, to make sure the water in our taps is safe to drink.

What safe water should be like

But the systems for treating water do not work equally well everywhere in South Africa.

According to the 2022 Blue Drop report, only about half of the country’s water treatment works are designed and maintained well enough to supply water that meets the national standards for drinking water.

These rules say what amount of chemicals such as chlorine, fluoride and sulphate is allowed in drinking water, how many and what type of germs there may be in water without people getting sick from using it, and what safe water should taste, smell and look like.

For example, for tap water to be safe it may not contain any germs that come from faeces, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella or cholera bacteria, as they pose an “immediate unacceptable health risk” to people who drink it because it can cause diarrhoea and vomiting.

The water also shouldn’t have any solid bits in it or be too cloudy — an indication that there are too many salts in it.

Municipalities with substandard waterworks are generally outside of the bigger metros, like in parts of the North West and the Free State.

[WATCH] How does cholera spread?

It is in these places where the risk of disease-causing bacteria such as cholera getting into tap water could be higher. In such cases, municipalities should tell residents to take extra precautions like boiling their water before using it for drinking or cooking.

Ayesha Laher, a water scientist and board member at the Water Institute of South Africa says that if the water quality from a treatment works isn’t up to standard, it means the treatment process isn’t working as it should. And so, there could be a risk of disease-causing germs ending up in tap water.

To check if your area has safe water, the department of water and sanitation has put together a dashboard that shows the quality of tap water. If you see a red pin, it means the water quality has not been checked for three months, and so it’s probably best to boil your water just to be safe. As for installing household water filters on taps, Laher says, they won’t protect you against germs “as they have no way to disinfect water” — at most they will remove sand and solid bits.

That we aren’t seeing outbreaks of other water-borne diseases, like hepatitis A and E. coli infections, means that, for now, the water treatment works are still functioning to a “reasonable degree”, says Tom Boyles, an infectious diseases specialist at Right To Care.

If the water quality were compromised, “we would see a large amount of these other diseases in people who drink tap water”, he says. It hasn’t happened yet, warns Boyles, but if it does, outbreaks like the one in Hammanskraal could become more frequent.

“The bottom line is, if it gets into the tap water, it’s a big problem.”

[Update 2023/06/08 16:29 This article was updated to reflect the latest cholera statistics for South Africa.]

Zano Kunene is a health journalist at Bhekisisa.