In a grim news cycle, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize’s announcement yesterday that the country is evaluating rapid tests for the new coronavirus is something to celebrate.

COMMENT

South Africa stands at a crossroads in the fight against the new coronavirus — and winning the battle will hinge on the decisions we make now about how quickly and how broadly we begin to test for the virus.

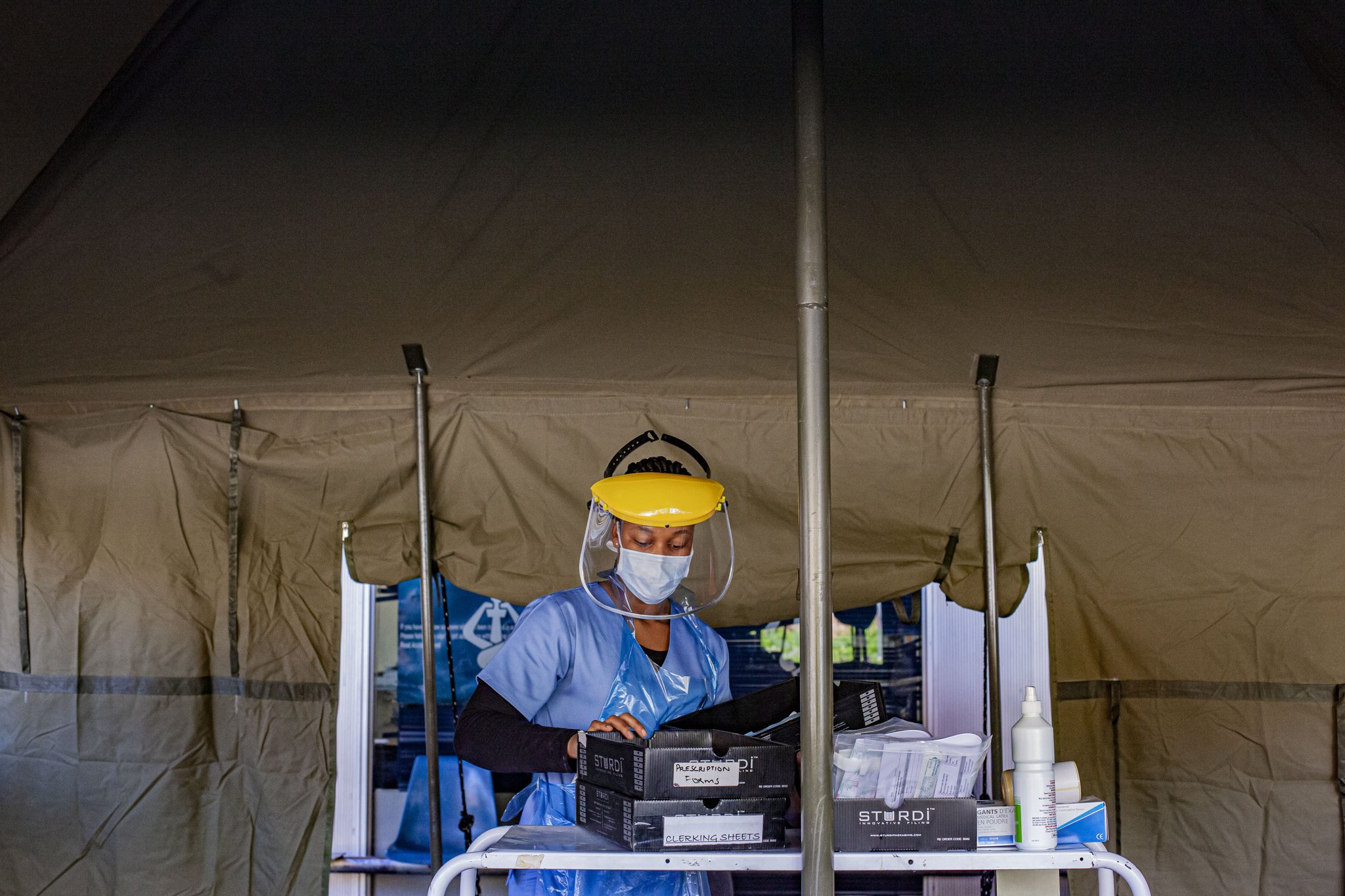

This week, government announced plans to embark on a massive campaign to trace people who have been in close contact with confirmed cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus. The country will also begin to increase screening or checking people for possible COVID-19 symptoms or risk factors to be able to refer those who need it for testing. New rapid tests, suitable for decentralised use, are set to be introduced in April. On Tuesday, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize also announced the country was also evaluating novel rapid tests for the virus.

Right now, who gets tested depends on who meets the criteria set out by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD). The NICD says that people with a serious respiratory illness and who also have at least one of the following symptoms, qualify for a test: A cough, sore throat, shortness of breath or fever (or a history of fever).

They must also have travelled to a high-risk country in the last 14 days or who have been in close contact with a suspected case of COVID-19 — this includes healthcare workers treating ill patients.

And importantly, the NICD has moved to also allow testing for anyone who has been hospitalised with an unexplained severe respiratory illness in line with what many countries around the world, such as Germany and Australia, now consider best practice.

Here’s why South Africa’s decision to expand the case definition of testing and to take it into the community, is a step in the right direction:

1. If we diagnose more people earlier, we can isolate them faster to break the chain of transmission

This is one of the cornerstones of the public health response to any epidemic. Isolation may be in hospital, at home, or in another community-based facility. Without widescale testing, we will miss infectious cases in the community, particularly milder cases, which allows transmissions to continue unchecked.

Also, if a person has a positive test and understands that they are infected, this knowledge empowers them to adhere to isolation policies to protect their family and their community.

2. Without more testing, we won’t ever have an accurate picture of what is going on

Intensified testing is essential to get a more precise profile of the epidemic in the country and each province, and to understand where transmission is occurring.

The first few cases in South Africa were in people who had acquired the infection in European countries and then returned home.

Then infections were reported in people who had been in close contact with known cases, and subsequent cases have been reported in people that can’t be linked to any other confirmed case.

However, the true number of these cases is not clear from the national health department’s daily reports. Meanwhile, there is little information released publicly around where those cases are located outside of naming the province in which they have been reported.

If we can get a more accurate picture of where transmission is happening, then we will be better able to target screening and testing to the high transmission areas — both during and after the lockdown.

Antibodies are the proteins our body makes in response to infection. New rapid tests that seek to detect these proteins – versus the real-time presence of the virus itself – can give us clues to the history of transmission in South Africa. If we don’t do this during the lockdown, then if the restrictions are lifted in mid-April, there’s every reason to believe that there will be a resurgence of transmission.

3. We need the data to contain the new coronavirus — but also to plan for it

Broader testing is critical to allow for data-driven decision-making, and particularly to inform more accurate projections about the need for healthcare workers, hospital beds, intensive care unit beds, and ventilators.

Without accurate data on the number of infections and the trajectory of the epidemic, any projection on what is needed from the health system has a lot of uncertainty attached to it.

4. Is it the flu, or is it the new coronavirus? The impending flu season will make it harder to answer this question

As we move into normal influenza season, differentiating COVID-19 from influenza will be difficult for healthcare workers, and we may need to be able to test simultaneously for both the SARS-CoV-2 and the influenza virus, especially if — by then — we have evidence to support specific treatments for COVID-19.

South Africa has an extremely advanced laboratory network for molecular diagnostic tests – each year, the National Health Laboratory Service performs millions of the kind of molecular testing needed to diagnose COVID-19.

And the country has more than 180 GeneXpert machines that are set to begin testing for the new coronavirus in April.

This is good news, especially as efforts increase to make mobile testing a reality. The challenge for us at present, as with all countries, is getting hold of diagnostic kits and reagents.

As the epidemic escalates in many countries around the world simultaneously, there is huge demand and competition for the test kits and reagents being produced by a limited number of companies.

Diversifying the kinds of tests we use, and introducing new ones, can help reduce our vulnerability to challenges like these.

But so can enlisting the help of our university laboratories. This has been done in the United States, where the University of Washington Virology Laboratory is doing up to 3 000 tests per day and has now done almost 80% of all tests in that state.

Similarly, United Kingdom academic laboratories are supporting a new national testing facility in Milton Keynes that will help the UK scale up from 5 000 to 25 000 tests per day, Nature reports.

As with many things in this epidemic, we need to learn from what’s working in other countries and also be creative in coming up with solutions that can work in this country.

In the United States, testing criteria for the new coronavirus was initially too limited but, as authors write in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a “sudden pivot to a far broader testing approach, even as capacity remains limited, may be an overcorrection”.

In South Africa, as in many other countries, diagnosing the new coronavirus will be a cornerstone of the response. Doing so will mean finding the sweet spot between what we want to achieve and what the health system can handle. We believe widening testing criteria to include people with acute respiratory illness is a start to finding this — and more cases of the new coronavirus.