- At the end of August, people over the age of 18 became eligible to get their COVID vaccine — the health department says they will make an announcement at the end of October about when vaccinations for those younger than 18 will start.

- But some young adults are still on the fence about whether getting the jab is worth it since they’re considered a low-risk group. The fourth round of the University of Johannesburg and Human Science Research Council COVID-19 democracy survey found that while overall acceptance of the vaccine had increased among adults, acceptance among those aged between 18 and 25 had declined from 63% to 55%.

- There are many pros to getting your shot — it protects you and those close to you. But don’t take our word for it, an infectious diseases expert helps break it down.

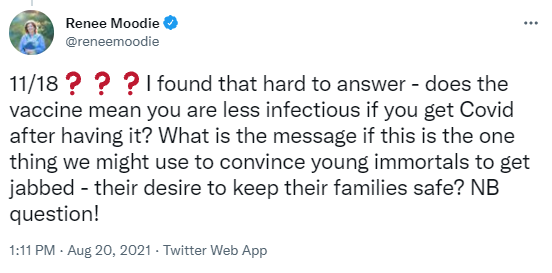

You’re still sitting on the fence about getting vaccinated. You have questions. You have concerns. We get it.

We try to answer as many reader questions about COVID vaccines as possible. In fact, our Mia Malan has turned answering these reader questions into part of her daily routine.

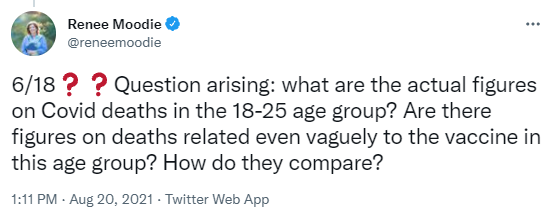

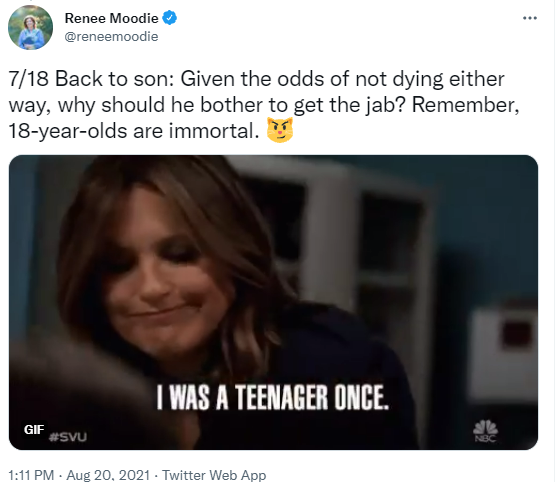

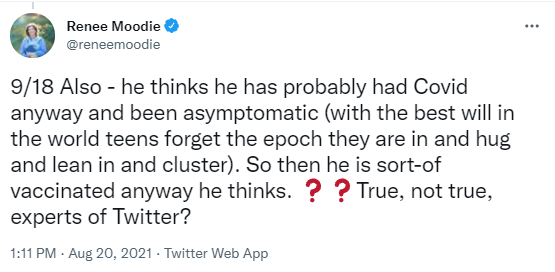

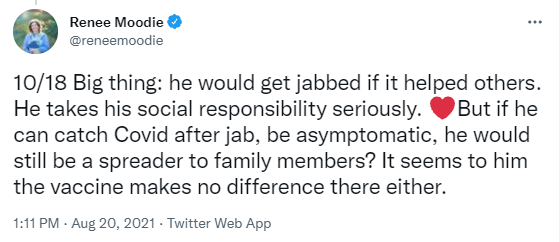

Take for example, this reader request from a mom whose son had questions of his own about the jabs.

These were arguably great questions (the whole Bhekisisa team agreed). So great we thought “why not turn them into a story?”

But we couldn’t field these questions alone.

We roped in a friend of Bhekisisa to help us reliably answer some of them.

Meet Richard Lessells, an infectious diseases specialist based at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Lessells has published plenty a paper on infectious diseases — most of them about HIV and TB clinical care quality. He works with the Centre for the Aids Programme of Research in South Africa (Caprisa) and with the KwaZulu-Natal Research and Innovation Sequencing Platform (Krisp). These are both credible organisations making serious strides in HIV, TB and genomic research respectively.

So Richard Lessells is a great person to field our questions. Here’s what he had to say.

Question 1: Are young people dying from COVID?

Young people are at lower risk of falling seriously ill with COVID than older people. This is what we’ve heard since the early days of the pandemic.

But do the numbers back this up?

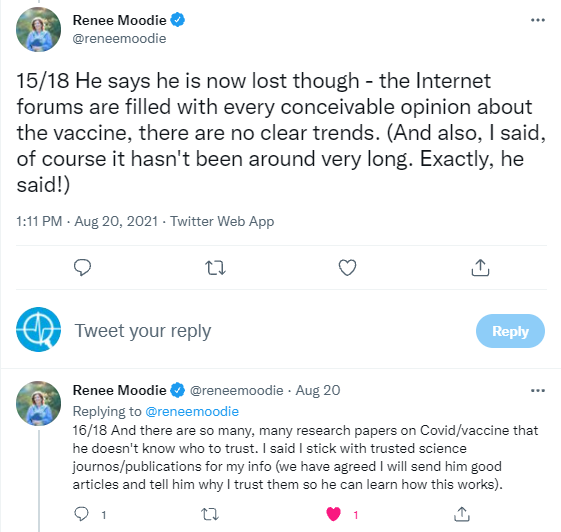

Yes — but with some caveats.

In South Africa, people over the age of 60 account for around 60% of COVID deaths in the country since the outbreak began on 5 March 2020.

Meanwhile, data from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) shows that people between the ages of 20 and 29 accounted for just over 1% of the 93 273 deaths recorded as of 6 October.

While we can’t know exactly what the numbers are for the age group mentioned in the Twitter thread (people aged 18 to 25), the NICD can give us a sense of how 15 to 24-year-olds fare in terms of COVID hospital admissions and deaths.

Between 5 March 2020 and 25 September 2021 a total of 686 young people 15-24 died in hospital due to COVID-related causes. This is less than 1% of all deaths recorded during this time.

So yes, young people are at lower risk of dying as a result of COVID-19. But that doesn’t mean they’re completely safe either.

As Lessells explains: “Although the risk of COVID in the younger age groups is clearly much, much less, it’s not zero.”

This risk also increases in young people who have underlying health conditions, like diabetes or high blood pressure.

Lessells further cautions that these numbers could be an underestimate of the true number of deaths faced by young people in this age group.

“As we know, the reported deaths and in-hospital recorded deaths don’t match up closely to the excess deaths data from the South African Medical Research Council,” he explains.

It’s also worth noting that with 23% of the population vaccinated, there is no link between getting a COVID jab and dying as a result of the vaccine.

Question 2: Why bother getting vaccinated as a young person?

Even though they’re at lower risk of developing severe COVID, it’s still worthwhile for young people to get vaccinated.

There are two possible benefits for young people to consider when contemplating whether to go get their shot, says Lessells.

The first thing to think about is that you have no way of knowing whether you’ll be in that 1% of 20-year-olds that need to be hospitalised. So why not give yourself the best chance?

COVID jabs work to protect you from severe disease — this means they lower your chances of needing to be hospitalised and they also make you less likely to die.

There’s also the issue of variants to consider. These newer versions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (which causes COVID-19) serve as a bit of a wild card when it comes to COVID.

For instance, the Delta variant (which was first identified in India and currently dominates infections in South Africa) is able to spread much faster than existing variants and seems to pose a greater risk to young people.

Data from the United Kingdom (UK) showed that people aged 5 to 50 were 2.5 times more likely to be infected with Delta. Another study from England also found that younger people are at higher risk of being hospitalised by Delta compared to the Alpha variant (first identified in the UK).

The second point to consider is that there’s still a lot we don’t know about how the body responds to COVID in the long run.

The long-term effects of COVID can affect even those with mild or asymptomatic disease, Lessells explains.

Around 80% of people who have had COVID continue to have symptoms after two weeks of diagnosis, according to an August systematic review of long COVID in Nature. The paper found that there were a possible 55 symptoms of long-term effects a person could experience, with the most common being fatigue.

The damage of long COVID — which can happen even in otherwise young and healthy people — also potentially extends to a person’s organs. There is some evidence to suggest after recovering, people have permanent damage to their heart, lungs, and potentially even their brain.

Another possible effect which has mainly been seen in children, is multisystem inflammatory syndrome, where parts of the body (such as kidneys and lungs) become inflamed.

Staving off these possible long-lived symptoms from infection could also be worth considering when weighing up the benefits of vaccination, says Lessells.

Question 3: What’s the use of getting vaccinated when you’ve had COVID already anyway?

It’s better to be safe than sorry.

The long and short of it is this: natural immunity — the type of protection you get against the virus once you’ve already been infected — will give you some protection against future infection. BUT that protection is variable and unpredictable.

What does that mean? Well, plainly put, it means you can’t depend on it.

“There are some people, unfortunately, that will not be protected as well as others,” explains Lessells. “They will have a weaker immune response after infection or they’ll have an immune response that wanes more quickly. And it’s one of those things where it’s difficult to predict who’s going to have a strong response and who’s going to have a weaker response.”

The immune system is your body’s way of protecting itself. It does this using different types of fighters — mainly your B cells and T cells. These different types of white blood cells act as defenders to get rid of germs, attack the virus and kill off infected cells.

B cells create antibodies which fight against the invading virus. T cells fight and remove cells which have already been infected by the invading virus.

When you’re exposed to SARS-CoV-2, your body has to fight off the virus using these internal defence systems. The shortfalls of that are not everyone has the same arsenal at their disposal.

Natural immunity isn’t a guarantee. In fact, studies show that 9% of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 won’t develop B cells and 7% won’t have detectable T cells.

There’s also still a lot to learn about how the immune system works against COVID. For instance, how strong the natural response is and how long it lasts could still largely vary from person to person.

Although not a high proportion, there is some evidence to show that 5% of people may lose their protection within a few months.

Vaccine immunity on the other hand reliably produces B and T cell responses and studies have found that B cell levels were much higher in vaccinated people than those with natural immunity.

So while natural immunity is good, it’s not good enough to bank on.

There’s also no harm in doubling down on protection.

Just because you may have had COVID previously, doesn’t mean vaccines have to be completely off the table.

In fact, jabs can help boost your existing immunity that you’ve built up from the previous infection.

For instance, Pfizer’s vaccine works using two doses. This means you get one shot and then come back after six weeks to get another. The first gets your immune system ready and the second jab serves as a “booster” to fortify your immune system. And the longer the time between shots, the better it is in terms of your protection.

The same logic applies to people who have already had COVID. The vaccine will serve as reinforcements for the protection you’ve built up on your own and help strengthen your immunity for a longer amount of time.

Question 4: Can you still spread the virus after getting vaccinated?

Vaccines do make a difference — not just for you but also for those around you.

The pro is that while you’re less likely to experience severe disease after being immunised, you also help protect those close to you.

That’s because the COVID jabs help reduce transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Here’s how it works:

First, vaccines make you less likely to be infected. In turn, this means your chances of carrying the virus and then passing it onto others are reduced, says Lessells.

Even factoring in variants doesn’t render the jabs entirely useless. For instance, the Delta variant did somewhat reduce the efficacy of vaccines — but the shots are still working to prevent transmission to some extent.

Second, no vaccine can give you a 100% guarantee of protection. That means even after you’re immunised, you could still get infected with the virus, but your chances of that are much lower. On the plus side, Lessells explains, vaccines do mean that in cases like these you are significantly less likely to be infected than your unvaccinated counterparts.

Question 5: If I’m vaccinated and still get COVID am I less infectious than if I weren’t vaccinated?

Short answer: Yes, you are less infectious after being vaccinated.

To understand why, let’s first break down what infectiousness is and its relationship to vaccines.

A person gets infected by the virus, SARS-CoV-2. This virus then attaches itself to the cells inside your body and begins to replicate. You spread the virus through particles released into the air (and ones that land on surfaces) when you talk, breathe, cough, or sneeze.

This transmission to others can happen even if you are asymptomatic. Therefore the more virus in your system, the more likely you are to infect others — even if you don’t know you’re sick.

As we already established in question 4, the vaccine lowers your chances of being infected. But more importantly, they also help to hinder the ability of the virus to replicate.

Why does that matter?

It’s simple. There’s less virus around for a shorter amount of time, explains Lessells.

COVID vaccines reduce the amount of virus in your body and this reduces your ability to spread the virus and infect others.

Existing jabs on offer also serve an important role in that they reduce your chances of developing symptomatic disease.

In other words, you’re not going to be walking around coughing and sneezing leaving virus particles in your wake.

That means people in your space are less likely to come into contact with these infectious particles and you’ve lowered the chances of you infecting them.

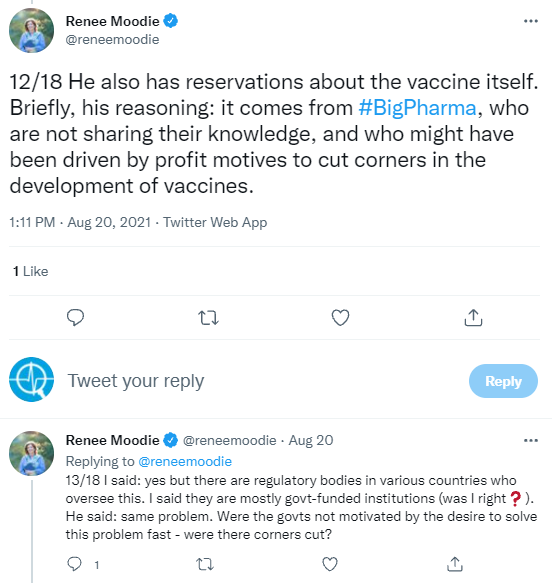

Question 6: Were corners cut in creating the vaccine?

COVID vaccines stand on the shoulders of giants. Their development relies on decades of scientific research.

“The development of these COVID vaccines was on the back of years and years of research into vaccine platforms for different diseases,” explains Lessells.

“The vaccines that were kind of developed most rapidly harnessed the technology that was known from vaccines for other infectious diseases, and [scientists] were able to rapidly deploy that vaccine platform for COVID.”

For example, since 2017 Johnson & Johnson has been developing the adenovirus vaccine technology currently being used for COVID. The only difference, they were testing it for HIV.

Remember, regulatory bodies are there to help protect you. Their main job is ensuring that nothing harmful is given to people.

The agencies review all the available information and then some to guarantee the safety of health products. With COVID vaccines, there’s also an extra measure in place where new information about the jabs is constantly supplied and assessed as global roll-outs continue.

Locally, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority, Sahpra, has been keeping a close eye on how vaccines behave in trials and out in the real world once administered to the public.

Want to know more about how this process works? Check out our breakdown of what goes into getting a COVID vaccine (or any other medicine) approved for use in the country.

Question 7: Why should you trust the vaccine?

Vaccines work and there is a considerable amount of data to prove this.

They offer protection to both you and those around you.

These jabs have been tested in trials on tens of thousands of people — and have now also gone into the arms of millions around the world.

This means we have data on how they perform in an ideal setting as well as in the real world. And all that data has shown us that these jabs are doing their job in a safe way.

Yes, the vaccines come with a small risk (as does any health product). But the benefits far outweigh that.

You may experience some side-effects after getting your shot. For the most part these will be mild like a headache or pain in your arm.

The good news: these are signals that your body is hard at work trying to shore up its defences and get your immune system ready to fight off SARS-CoV-2 infection.

It’s natural to have concerns or be a bit hesitant about getting your jab. The important thing is to seek out information and find answers for any lingering questions you may have.

Bottom line: These vaccines are safe, they reduce your risk of getting sick and infecting others, and as an added bonus the jab helps reduce your chances of falling severely ill.

Question 8: How should you make sense of all of the available information?

There’s a lot of information out there — some good, some bad and some kind of in the middle.

Luckily, there are plenty of people out there sifting through the data to make it more accessible and understandable.

The first step for you is: decide what the most reliable source of information is. The website and reports of the NICD, the US government’s Centres for Disease Control and the World Health Organisation are good starting points.

Then ask tough critical questions, pause and verify before you share.

It’s easier said than done but it’s definitely a good starting point.

And, should all else fail, remember that we’re only a thread away.