- Last week, the south coast of KwaZulu-Natal was mopping up damage after being battered by heavy, unexpected rainfall over the weekend — almost 50 times more in 24 hours than what the usual daily average is here.

- Extreme weather events like this will happen often and become more intense as our planet’s climate changes, experts say, and buffering communities against them needs political will.

- Yet climate change gets fairly little attention in election talks. Voters say this is not okay.

What do our political parties have to say about climate change this elections? Not much, says Linda Pretorius in today’s newsletter. Sign up.

COMMENT

With 4.2-billion people across 50 countries — almost half the world’s population — voting for their next governments this year, “the biggest threat to security that modern humans have ever faced” should be at the top of election talks.

Yet worldwide climate change is getting fairly little airtime in politicians’ campaigns.

From reading the manifestos of the 16 largest political groups in South Africa’s upcoming elections this year, it’s clear that their understanding of how deeply entangled the relationship is between the country’s action on climate change today and our prospects for prosperity and social safety in the future is worryingly shallow — while the electorate is much more clued up.

Last week, the south coast of KwaZulu-Natal was mopping up damage after being battered by heavy, unexpected rainfall over the weekend — almost 50 times more in 24 hours than what the usual daily average is here.

Experts say changing weather patterns will likely cause about 250 000 extra deaths a year from around 2030 and make infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV spread more easily, especially as extreme weather events like heatwaves, storms, floods, droughts and wildfires are set to happen more often and become more intense. For example, although there were only slightly more such events in 2022 than the global 20-year average, almost twice as many people died from floods, extreme temperatures and droughts alone and economies lost $36-billion (about R695-billion) more than before — that’s close to 9% of South Africa’s gross domestic product.

Numbers like these make the low political priority given to climate change hard to fathom — not least given that, if we keep on pumping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide into the air at the rate we’re going now, we might have only six years left to have a reasonable shot at stopping the Earth’s air from becoming more than 1.5°C warmer than it was before the industrial revolution in the mid-19th century.

This temperature rise is the limit that climate experts say we can buffer before ecosystems, water and food supplies, and people’s health and livelihoods become seriously threatened — which means real action is needed now.

As part of a research project called Money Talks, which polled 30 000 people from 15 countries — rich and poor — to find out what they thought about public investment in responding to climate change, we asked 2 000 South Africans of different ages, income, race and gender groups and from across the country to add their voices.

The results completely surprised us. Here are the three most enlightening findings.

1. Climate change ranks high as an election issue

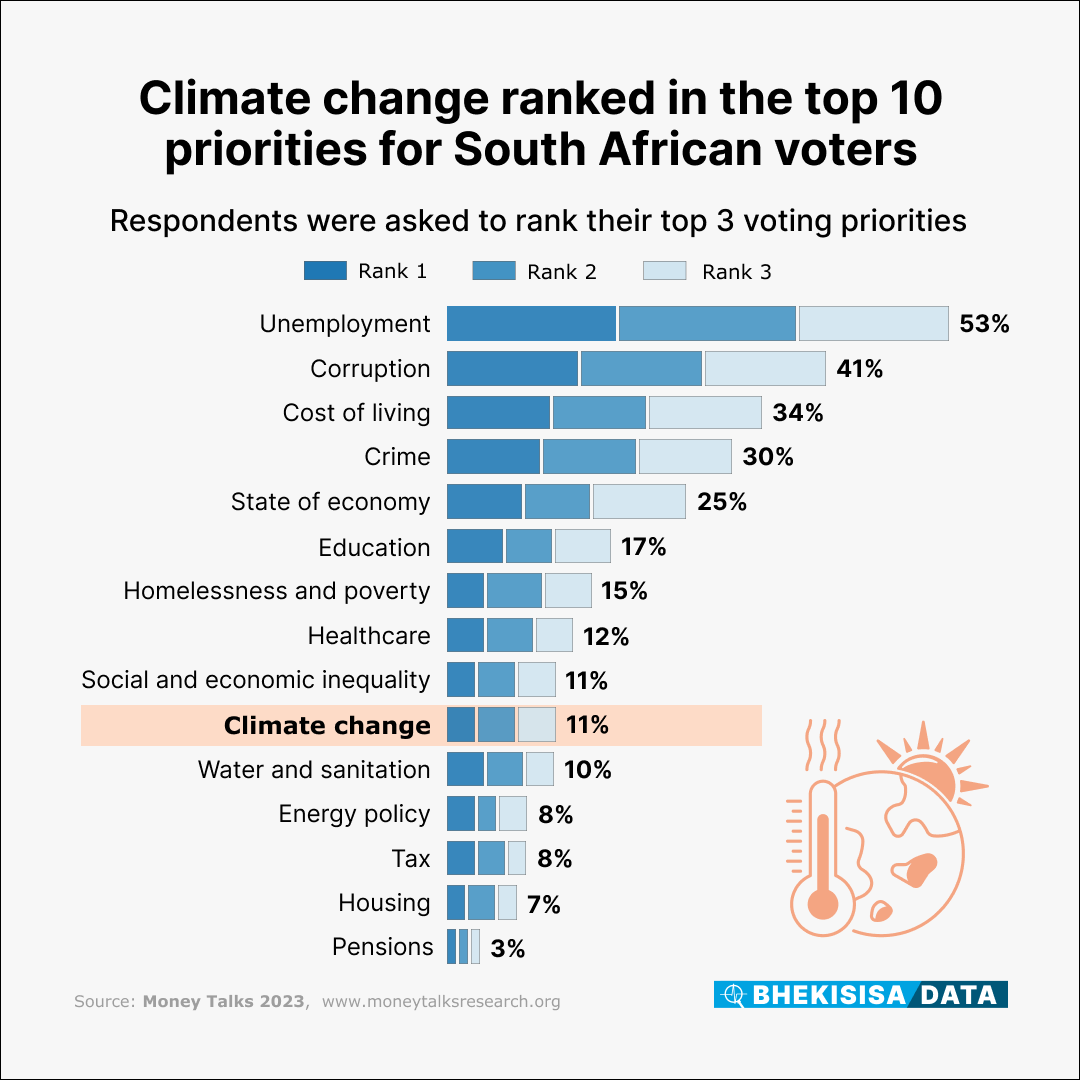

Unemployment, corruption and the cost of living are the top-most priorities for South African voters, causing most concern for between a third and about half of respondents. We were not surprised, given that close to a third of the country’s adults don’t have jobs, state capture has eroded public services and our trust in them, and the prices of food, consumer goods and services like power and healthcare have gone up and up in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and global conflicts.

But what did surprise us was that climate change was one of the top ten priorities for voters, with 11% of participants saying it’s one of their top three issues. It outranked issues such as water and sanitation, having access to social security (for example, pension funds or government grants) and the country’s energy policy. Given that almost a third of the population rely on social grants every month and the dire consequences of power outages for the economy and people’s lives, we’d expected these last two issues to feature higher.

2. The effects of climate change hit home

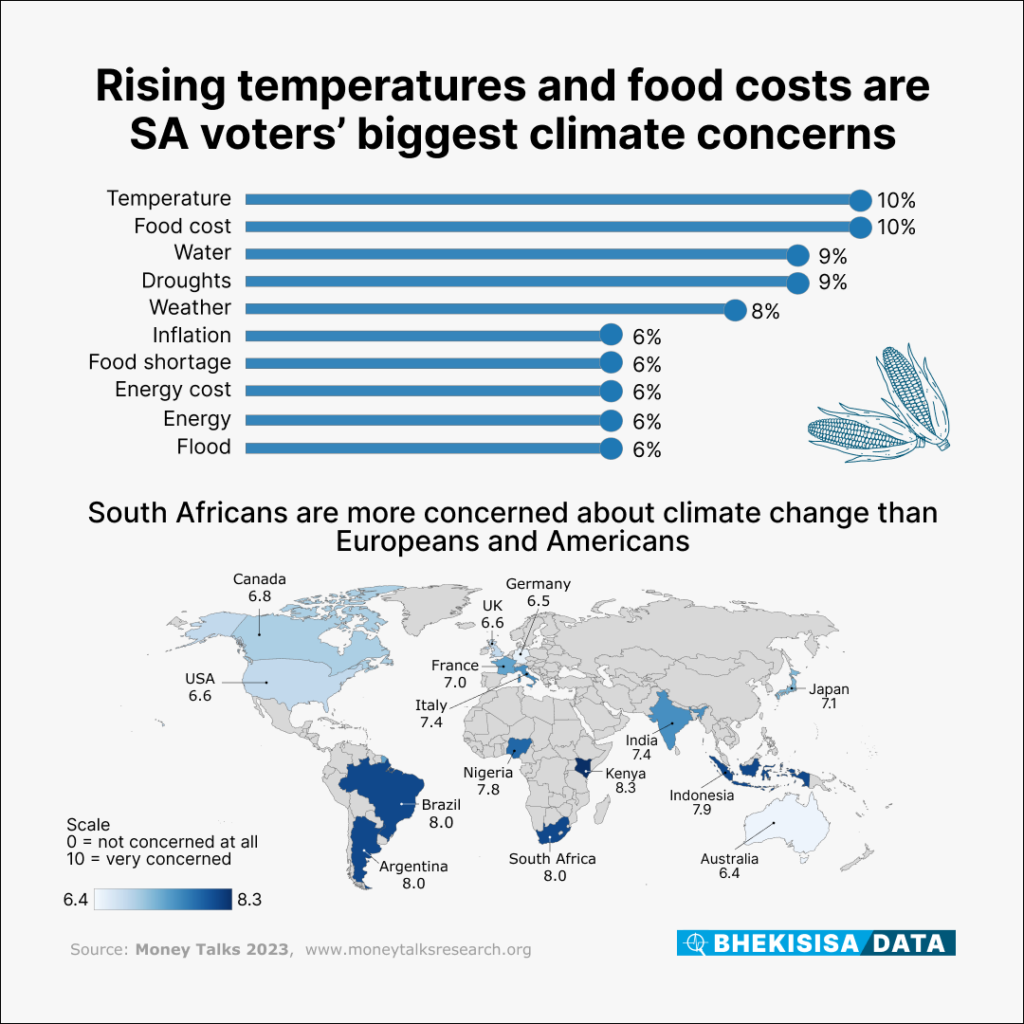

The polling data showed that our respondents, regardless of age, education level or where they lived, were really worried about climate change making life worse in the future. Their biggest fears were about living in hotter conditions, that food would get more expensive and that water would get scarcer, including because droughts could become more likely.

On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 meant not being stressed and 10 meant being very concerned, South Africans’ concern about the negative effects of climate change scored an average of 8.0 — almost 18% higher than the average from people in richer countries like Italy, France and Canada. This was similar to the level of worry in other developing countries such as Kenya, Nigeria, Brazil and Argentina, which research shows will be hit harder by the effects of changing weather conditions despite contributing much less to their causes than high-income countries.

3. It’s worth spending money on climate change — now

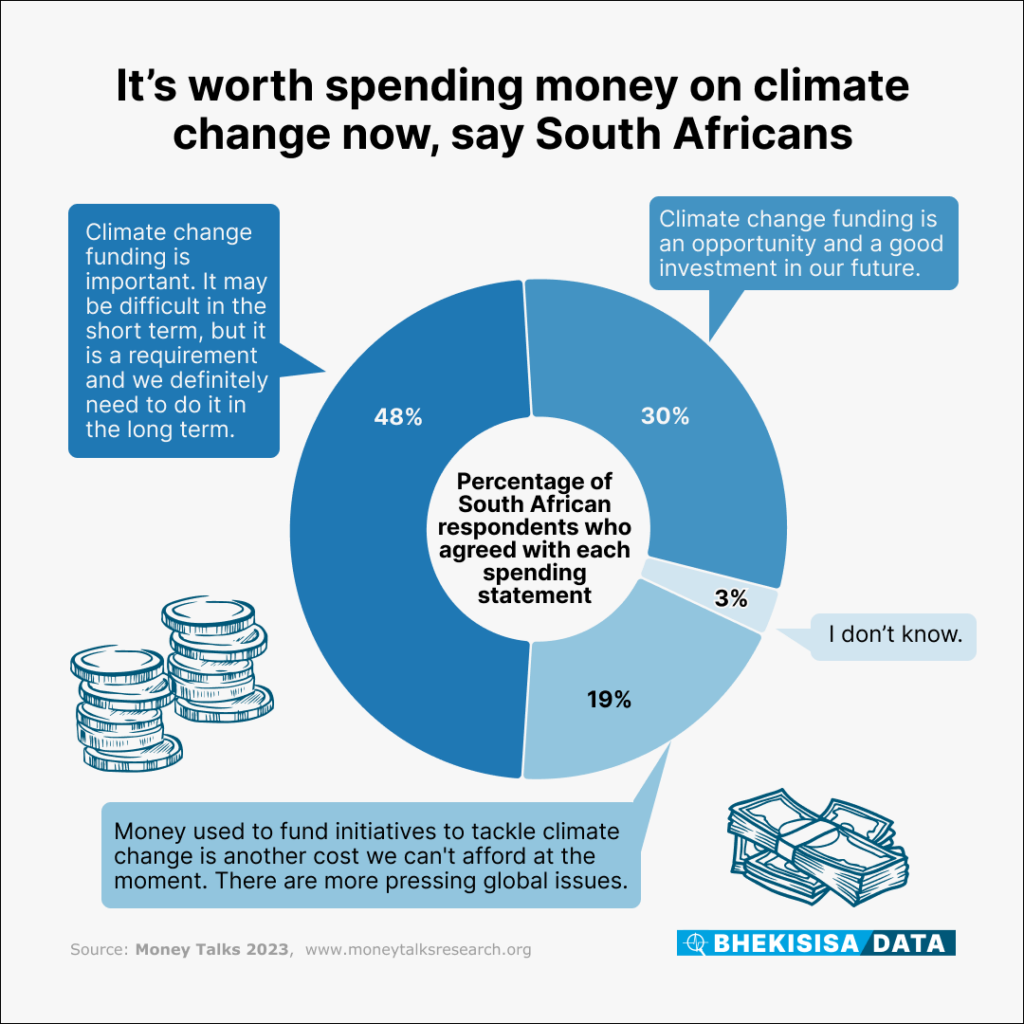

When we looked deeper, we found that respondents thought that, as tough as investing in dealing with the effects of climate change might be now because of the cost of fixing more pressing problems such as loadshedding in South Africa, it’s a necessary investment in our future overall.

This is big, because it tells us that ordinary people understand much better how climate change is linked to life becoming harder and how it will continue to threaten wellbeing in the coming years than what politicians give them credit for.

Moreover, when voters feel the choices they’re given will lead to better environmental outcomes and an easier life, support for spending on climate action can climb by as much as 15%. This very simply means that South African voters respond well to political messages that show them how investing in ways that deal with the causes and effects of climate change now will lead to a more stable economy and better, more reliable services — such as healthcare — today and in the future, even with increasing odds of poor health because of bad weather conditions.

What climate change means for public health in South Africa

When things like water and sewage systems, power lines and roads are damaged because of extreme weather events, it’s difficult for people to stay healthy. This has practical implications for how we organise the public health system to adapt to how climate changes affect our wellbeing.

For example, in the harsh floods in KwaZulu-Natal in 2022, many people lost their homes and possessions or had to move away, which meant it was hard for those with chronic conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure or HIV to get their medication. The floods also added stress and anxiety to people’s lives, which heightened both the risk and occurrence of mental health illnesses. When, on top of that, an already stressed health system has to deal with, for instance, many cases of diarrhoea because water sanitation systems have been destroyed, the consequences of not investing in preparing for the fallout of a changing climate snowballs.

In regions like the Mpumalanga Highveld and the Vaal Triangle, where power stations and factories rely on burning or processing fossil fuels like coal and oil, people living close to these industries breathe in air so dirty that many develop lung diseases or heart problems and conditions like asthma get worse. In these places, people who are unemployed — either because of job cuts or because they’re too ill to work — depend on government hospitals and clinics. But the public health system is so stretched that it’s hard to give people the right care or change to systems that will solve the underlying causes of poor health here, including getting the country to switch to cleaner energy sources instead of relying on coal.

Our study did not poll whether South Africans felt their political parties were ready to do what’s needed to help the country adapt to climate change. What it did show, though, is that people are not only worried enough about climate change to rank it among their ten highest voting priorities but also that they want to hear politicians taking it seriously — for a better future.

Sekoetlane Phamodi is a development worker with over a decade’s postgraduate experience in building public policy and advocacy initiatives on information and communication rights, media development, and good governance in South Africa and the continent. They currently work as programme director of the New Economy Hub.