In South Africa, HIV infection is no longer a death sentence but in countries like the Democratic Republic Congo, it’s as if treatment never happened.

South Africa now boasts the world’s largest antiretroviral treatment programme. Of the almost seven-million people estimated to be living with HIV in the country, 3.4-million are now on treatment, according to health department figures.

But in 2000, it was a very different story.

That year, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) opened the doors of the country’s first antiretroviral clinic in Khayelitsha. As news spread of the life-saving treatment being offered there, people living with HIV came en masse. We saw the sickest of the sick; people were brought into the one-room clinic on stretchers or wheelbarrows.

The patients who were carried or wheeled through our doors then were often extremely thin or dehydrated from persistent diarrhoea. They were suffering the unthinkable. Our doctors could not get patients on to antiretrovirals fast enough.

For the many in South Africa who were able to get lifelong treatment, this is a dark memory.

For our patients in West and Central Africa, this is their reality. In our clinics in countries such as Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic, patients arrive showing signs of Aids – or the late stages of HIV infection – that have become relatively rare in South Africa. Their bodies’ immune systems have collapsed and deadly opportunistic infections have taken over.

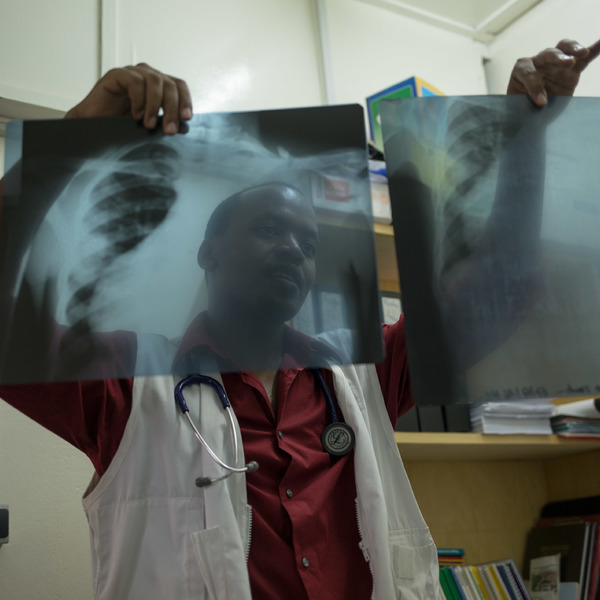

MSF now supports advanced HIV units in national hospitals situated in the capital cities of Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic. Often carried in by family or friends, our patients arrive extremely thin and in severely altered mental states.

Our patients arrive so sick that a third cannot be saved.

At these centres, we partner with health ministries to provide free, high-quality care and treatment for people living with advanced diseases caused by HIV, including the HIV-related cancer kaposi sarcoma, as well as brain infections such as cryptococcal meningitis and cerebral toxoplasmosis. But even for the very sick, the huge stigma surrounding HIV adds to the many hurdles to seeking care openly.

When we began providing antiretrovirals in South Africa more than 15 years ago, stigma dropped steadily as people realised: it’s not only me, there are thousands all around who are HIV positive.

In Central and West Africa, the fewer who seek treatment, the higher the stigma. It is a vicious circle.

Many HIV-positive mothers refuse to get their children tested, says one professor conducting paediatric HIV testing. Without antiretroviral treatment, a third of HIV-positive babies will die before their first birthday and more than half will never see the age of two, according to a 2004 study published in The Lancet medical journal.

Many countries in the region have low proportions of people living with HIV. In Guinea, for instance, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and Aids (UNAids) estimates that 1.6% of the population is living with the virus. But low percentages hide huge numbers – 120 000 Guineans are HIV positive.

Low HIV prevalence rates and high levels of stigma mean that HIV is not prioritised in countries’ health systems. Many people are either diagnosed late or not at all. Those who have been diagnosed with HIV often face treatment interruptions because of stock outs, a lack of money to pay for treatment or an inability to get to health facilities.

Those who develop resistance to initial HIV antiretroviral regimens because of these interruptions may never be diagnosed with treatment failure and switched on to appropriate medication.

In Guinea, the country’s few HIV testing services and treatment options are barely available to poor people because of crippling patient fees and chronic medicine stock outages, including those affecting drugs for opportunistic infections. As a result, only 5% of Guineans have access to HIV testing and just over a quarter of those diagnosed with HIV get treatment.

The situation in Guinea reflects that of the West and Central Africa region: barely one in four people get the treatment they need. Our teams see the impact on the ground: in Central African Republic, where 450 000 people live with HIV, Aids-related illnesses have been the leading cause of death among the general population since 2000.

West and Central Africa now account for one in five new HIV infections and a quarter of Aids-related deaths globally. Almost half of all children born HIV positive in the world today are born in the region.

Neglecting this region will be a tragic, strategic mistake: Leaving the virus unchecked to do its deadly work in West and Central Africa not only risks lives but also jeopardises international goals to curb HIV worldwide.

In South Africa, the increase in free testing and treatment for HIV – as well as for tuberculosis – has saved hundreds of thousands of lives. The same must happen in West and Central African countries.

All patients should receive between three- to six-month supplies, ideally through the community-based drug deliveries being rolled out today in South Africa. During the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, an MSF pilot project gave patients six-month supplies of ARVs, allowing people to stay on treatment while clinics were shut.

Investing in education and communication to address stigma and promote HIV testing and treatment is equally vital. Hospitalisation for late-stage HIV should not be the last resort to treat the suffering we see.

South Africa saw almost 400 000 new HIV infections and 180 000 Aids-related deaths in 2015, according to UNAids.

HIV remains the number one public health priority in South Africa. But the country has shown us that widespread access to treatment reduces stigma.

Although efforts against HIV need to be increased in Southern Africa, the people left behind over the past decade in West and Central Africa should not be forgotten once again.

Ambitious plans and directing available resources into effective strategies and models of care are needed to save lives and prevent new infections. This has to include access to free treatment and care as patient fees remain a major barrier to healthcare access for patients.

The situation in West and Central Africa represents a ‘now or never’ moment in the global HIV response.

Gilles van Cutsem and Ousseni Tiemtore are HIV and TB advisors with Doctors Without Borders.