From how to spice up your sex life to the more mundane, “does this look weird to you”, there are some questions you just don’t want to ask your friends and family. Relax. Now, there’s an app for that.

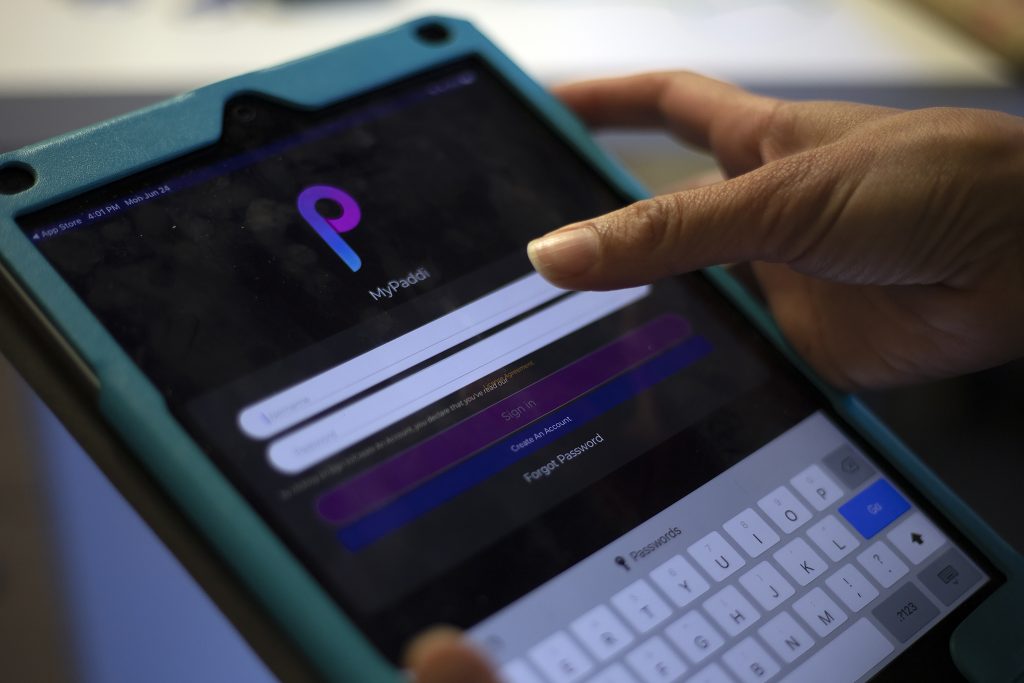

Leon Abbo and his girlfriend had a question. Okay, they had a sex question. They didn’t want to ask a friend — that was too weird. And a doctor? Well, it would be a lot of trouble and money for something they weren’t even sure was an issue. So instead, the 27-year-old Nigerian picked up his phone and pressed a blue and pink “P” icon from his app list.

A sexual health app called myPaddi popped up. Abbo clicked on “The Zone,” the app’s community forum, and typed in his query.

“What is the cause of whitish discharge from the vagina?” he asked.

Within minutes, replies began popping up on the screen, mostly from women in the group.

“Some told me it could be a normal discharge associated with some women when they are aroused sexually,” he remembers. “Others encouraged we see a doctor.”

Armed with that knowledge, Abbo and his girlfriend decided to check in with a doctor in their hometown, who confirmed what they hoped. There was nothing to worry about.

They were thrilled, he says. And better yet, no one in their real lives had to know what happened.

That was exactly the intent behind myPaddi, whose name is slang for “my close friend”. The app went live in Nigeria in July and since then has been downloaded about 13 000 times in almost two dozen countries, 18 of them in Africa, says developer MOBicure. Nearly half of all users— most of whom are Nigerians between the ages of 14 and 29 — check the app at least once a month.

The firm’s co-founder, Charles Akhimien, was inspired to create the app by his own experience as a young doctor. In a country where abortion is illegal except in cases where it’s needed to save the woman’s life, Akhimien saw three teenage girls die from complications following home terminations.

Only 11% of Nigerian women between the ages of 14 and 49 use any form of modern contraception, the country’s 2013 demographic health survey shows. The proportion of teenagers who could say the same was less than half that.

Not surprisingly about a quarter of Nigeria’s 9.2 million pregnancies in 2012 were unintended, a 2015 study published in the International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health estimates. About half end in abortion.

The lack of contraception and high rates of unintended pregnancy without access to safe abortions is a deadly mix. Nearly one in three women of reproductive age will die of pregnancy-related causes, the demographic and health survey reveals.

The girls’ deaths, Akhimien says, haunted him. Eventually, he quit his hospital job to work full time developing solutions to old problems with new technology.

He explains: “Young people in Nigeria and Africa lack access to sexual and reproductive health information that is accurate and does not give them the facts either from a religious or cultural angle.”

Earlier this year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) named Akhimien’s discreet, straight-talking app among its top 30 finalists in its Africa Innovation Challenge.

So, what makes a good health app?

But Akhimien’s creation is just the latest addition to a rapidly growing field called mhealth, which tries to use the power of mobile and wireless devices to improve healthcare. The market for apps that can make you fit, remind you to take your medication or even track your menstrual cycle is growing so fast that the United States-based Zion Market Research firm estimated in January that it would be worth US$111.1-billion by 2025.

Apps, their proponents say, are particularly useful for getting sex education to young people who, for whatever reason, aren’t able to access it from educators, health workers, or family members in their real lives.

And a 2016 study published in the journal Pediatrics suggests they’re right. Teens surveyed for the research were keen to get information on a range of sensitive questions in online forums or via short messages because the information was confidential and easy to understand and share. The study reviewed more than three dozen studies on sexual and reproductive mobile phone health apps.

But the scientific evidence about what works isn’t keeping pace with the burgeoning number of mhealth tools at countries’ disposals, the WHO says.

And what research does exist often varies too widely in scope, quality or methods to be easily compared. That’s why a WHO expert body released a 16-point checklist to help researchers evaluate mobile phone health apps like myPaddi.

What does proper research on health apps look like?

Well, it spells out just how widely available the technology the app needs is, such as network coverage or mobile phone penetration. It also describes, for instance, how researchers fined tuned the product along the way and what may get in the way of making it available to larger groups of people.

And useful mhealth apps and projects also explain how user information is kept confidential and, according to the checklist, how they ensure information is accurate and in line with the latest guidelines.

In Nigeria, myPaddi uses local doctors to not only write content from “what are the advantages of female condoms?” to “what should I do if I’ve been raped?” but also to moderate forums. This means doctors can quickly correct bad information given by other users or delete comments outright.

Perhaps the most useful feature is that myPaddi users can access real-life doctors for personal, one-on-one consultations, by purchasing credits in the app at the cost of 300 naira (R12) for 20 minutes. Sounds cheap? Doctors’ fees are subsidised by the app’s donors, Expo 2020 Dubai and the United States African Development Foundation.

Akhimien says he doesn’t expect those sessions to be a substitute for real-life visits to a doctor — they are, however, a useful first step to getting young people, who may be shy or embarrassed about a sexual health problem, to begin discussing it with a professional.

- You may also be interested in: Why health experts should be on Twitter

He explains: “We are simply bringing healthcare to the fingertips of the people using mobile tech.”

In most cases, Akhimien says, the doctors on his app end their session by encouraging the patient to seek a second option from an in-person doctor’s visit.

Almost half of myPaddi users said they joined because they wanted to chat with a doctor or were seeking reliable health information, a recent internal MOBicure survey shows.

The app’s initial success has been a good start in getting accurate information out there, but

Akhimien thinks it can do better.

“What we want to do next is to actually break down the numbers to see how exactly [the app is] helping users make decisions towards reducing HIV and sexually transmitted infections as well as unwanted pregnancy,” he says.

Akhimien also hopes to eventually make the app financially sustainable and reduce its dependence on donor funding, but he is vague about how, exactly, myPaddi will make that happen.

What he does know, he says, is that finding a way to keep the app going is vital to users who have found new freedom around sexual health in myPaddi’s anonymity.

“You know, you cannot [always] remove the stereotypes in people’s minds, so [using an app] gives me a kind of freedom,” explains John Osawe, a user from Benin City, Nigeria. “I can ask a question relating to me in the community, and I can walk past the person who is using myPaddi, and the person would not know me.”