- Bhekisisa and Media Hack Collective’s 2021 #SayHerName project, researched what gender-based violence stories make it onto the news.

- The data backed up what we know anecdotally — that murders of women like Reeva Steenkamp and Leigh Matthews are the ones that get covered — celebrities, young pretty women, murders that are gruesome or salacious.

- That Steenkamp and Matthews are white women doesn’t lessen the tragedy suffered by them or their friends and family by any means, but it does underscore the stories and voices that are being left out, including those of women living in poverty or those living in rural areas.

- In 2015, we travelled to Diepsloot outside of Johannesburg to give such victims a voice. But we also looked at why men rape — one of the most common characteristics among perpetrators is that they had traumatised childhoods.

- Our government health sector has, unfortunately, only just over 250 psychologists — making addressing men’s unprocessed trauma close to impossible.

In today’s newsletter Mia Malan and Tanya Pampalone walk you through how helping men deal with childhood trauma can help end gender-based violence in SA. Sign up.

COMMENT

On November 24, South Africa’s department of correctional services announced that former star athlete Oscar Pistorius would be free on parole in January, nearly 11 years after being found guilty of murdering his model girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp. The story of his impending release made headlines around the world.

Before the parole hearing outside the Kgosi Mampuru Prison in Pretoria, the Steenkamp family’s spokesperson, Rob Matthews, prepared to read Reeva’s mother, June’s, victim impact statement. Matthews noted the bitter irony of the launch the following day of 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, which begins each year on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and runs through December 10, Human Rights Day.

“I’m not sure what that does,” said Matthews, whose daughter, Leigh, was kidnapped and murdered in 2004. “Because you [continually] read the paper about the tragedies that have taken place … it just leaves me cold.”

Whose stories get told?

Bhekisisa‘s #SayHerName project, which we produced with the data journalists at Media Hack Collective and was selected for inclusion with 10 other projects for the Global Investigative Journalism Network’s guide Investigating Femicide, researched what gender-based violence stories make it onto the news. The data backed up what we know anecdotally — that murders of women like Reeva Steenkamp and Leigh Matthews are the ones that get covered — celebrities, young pretty women, murders that are gruesome or salacious. That Reeva and Leigh are white women doesn’t lessen the tragedy suffered by them or their friends and family by any means, but it does further underscore the stories and voices that are being left out, including those of women of colour, women living in poverty or those living in rural areas.

United Nations statistics show one in three women experience physical or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime. Recent global estimates show that, on average, more than five women or girls are killed every hour somewhere in the world by someone in their own family.

Compared with other countries where statistics are available, South Africa ranks among the highest female homicide rates in the world. But it has taken years to inch forward on concrete plans to combat the violence. In October the National Assembly approved the long-awaited National Council on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide Bill. Once the Bill is signed into law, a national council will be launched, which will develop a national strategic plan within six months.

Too little, too late

But for the thousands of women and children already subjected to gender-based violence in South Africa — just between July and September there were 10 516 reported rape incidents — it is far too late.

In her victim impact statement, June Steenkamp, who didn’t appear at the parole hearing because she could not “muster the energy” to face her daughter’s killer again, said at least Reeva’s murder will “continue to raise awareness around gender-based violence worldwide”.

She’s right. It is very likely that stories like Reeva’s will be the ones that help amplify the epidemic of violence against women and children. Hopefully it will also turn up the volume of the voices of those whose stories we will never hear.

Spending time to tell such stories can be incredibly impactful.

[READ] Diepsloot: Where men think it’s their right to rape

In 2015 Bhekisisa travelled to Diepsloot in Johannesburg to document the experiences of victims of child rape. Our story resulted in a United Nations panel, which was investigating violence against women, visiting the township. There were also tens of thousands of rands of donations for The Green Door, which helps abused women and children in Diepsloot and the local police station’s head being taken to task for not assisting victims correctly.

Our coverage went beyond giving victims a voice: we also investigated the driving factors of rape and returned in 2017 to look at further research and attended workshops in the township which attempted to address gender-based violence.

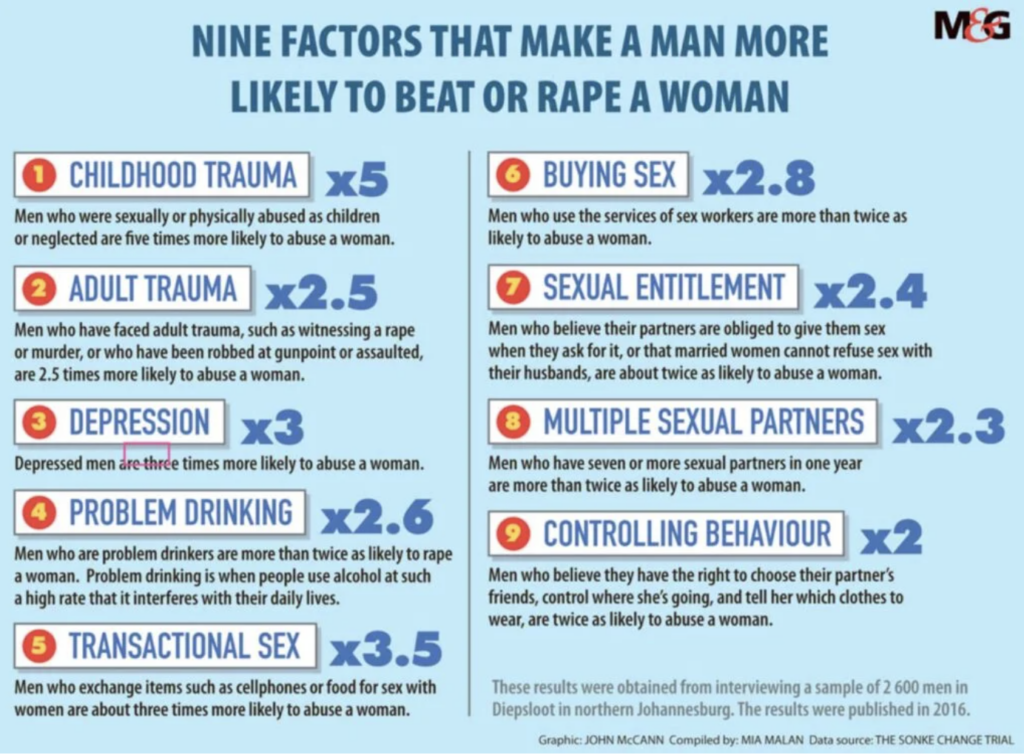

A survey by Sonke Gender Justice in Diepsloot showed two of the most common characteristics of violent men are that they were abused themselves as children or faced adult trauma such as witnessing a rape or murder, or have been robbed at gunpoint.

Two more common features are depression and problem drinking.

But, worryingly, a South African Medical Research Council study shows two out of three men, who admitted to scientists that they had raped a woman, said they did it because of sexual entitlement, in other words, because they believed sex was owed to them.

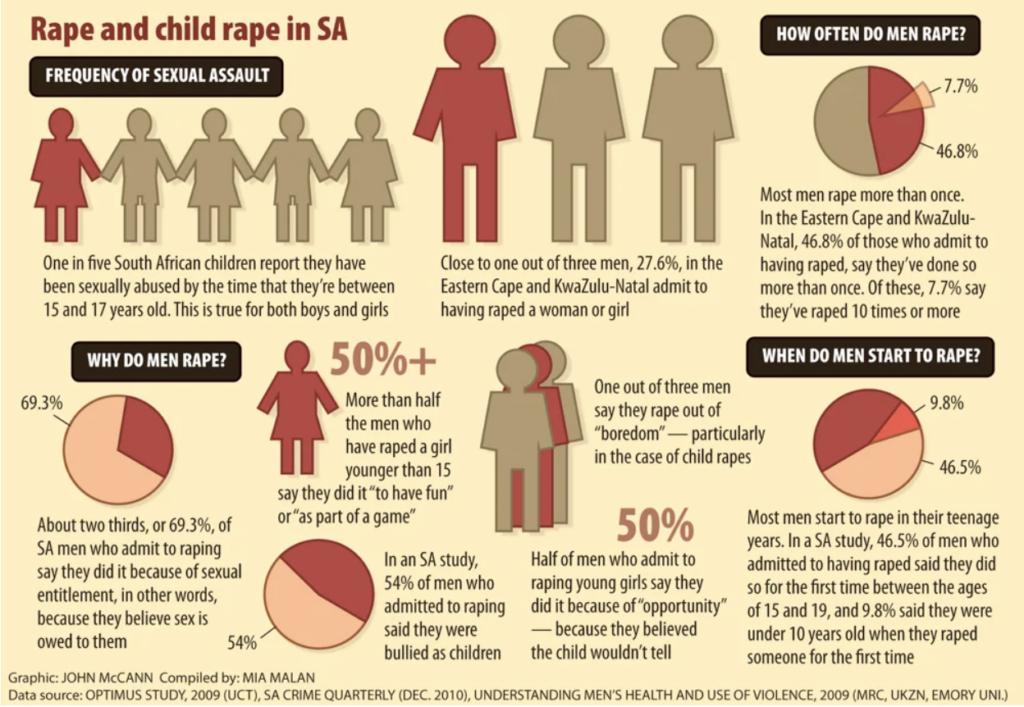

More than half of those who had raped a girl younger than 15 said they did so “to have fun” or “as part of a game”.

However, just as many said they had been bullied as children.

If we don’t address men’s unprocessed trauma in South Africa, we’re going to get nowhere with solving gender-based violence.

But counselling services are almost non-existent in our public health sector, which most of the country relies on.

Provincial health departments employ only 250 psychologists and 217 psychiatrists in eight provinces (Gauteng wasn’t included in this survey).

South Africa does have 2 500 registered counsellors, whose services cost half that of psychologists’, but most of them can’t find work in the public sector, where they’re needed most — because there’s no budget to employ them.

About one in three people in South Africa will experience depression, anxiety or a substance use disorder such as alcoholism at some stage in their lives, according to the 2009 South African Stress and Health Survey.

Yet three quarters of those who suffer such mental health conditions will never be treated, a 2009 South African Medical Journal study found.

Without investing in mental health services our country will stay sick — and gender-based violence will be part of our make-up.