- Tobacco companies are using clever marketing tactics to make so-called new-generation tobacco products like vapes and nicotine pouches look cool — and punting them as less harmful than conventional smoking.

- It’s a ploy to get a new generation hooked on tobacco, says a new World Health Organisation report, ahead of today’s World No Tobacco Day.

- How do South Africa’s tobacco laws stack up against international guidelines — and are they strict enough to keep young people safe?

In today’s newsletter, health reporter Christina Pitt looks at the impact of Big Tobacco’s marketing on young people. Sign up.

Big things happened in South Africa in 1993. United Nations economic sanctions against the country were lifted, an interim Constitution that would lead to a democratic rule got the go-ahead, and Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

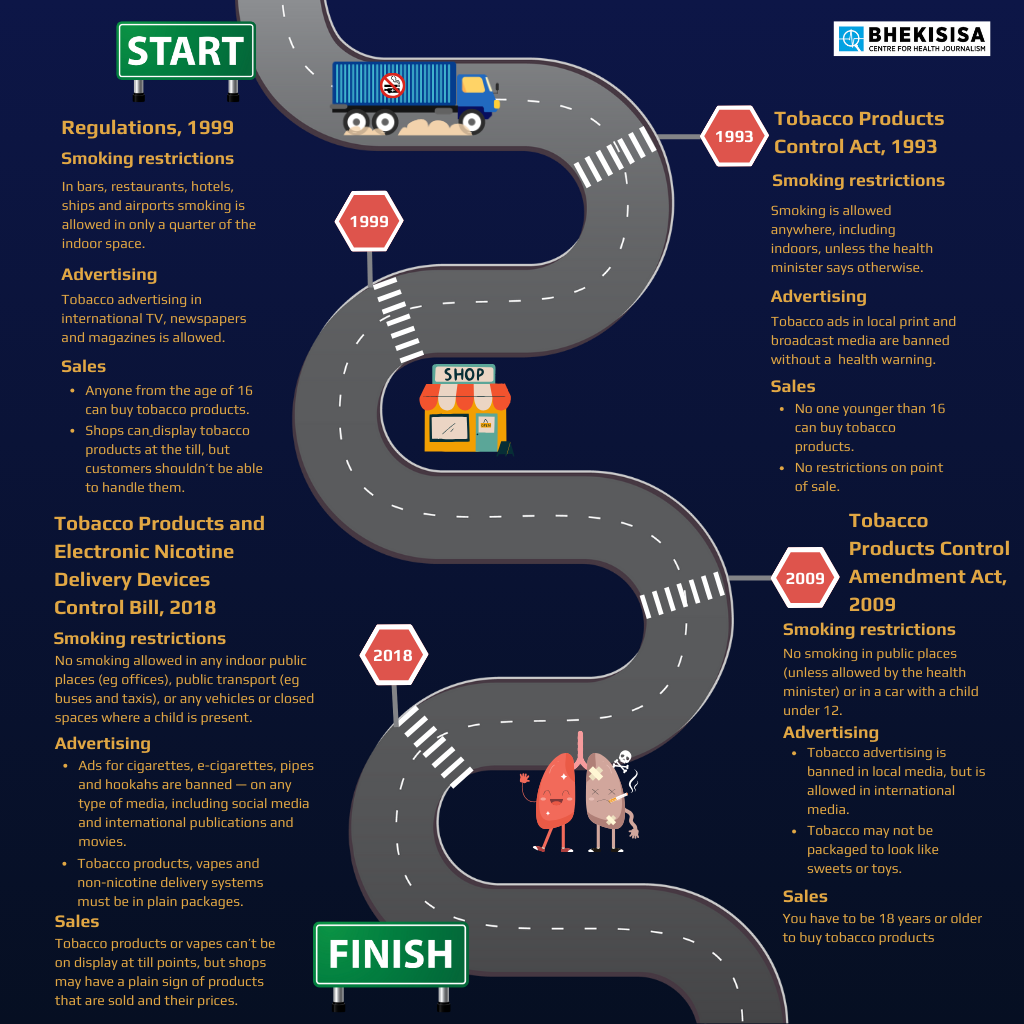

It was also the year that the noose started to tighten for smoking in South Africa, with the government passing the Tobacco Products Control Act.

Within the first 20 years of legislation, the number of adult smokers had dropped by about half and by 2011, about a quarter fewer school children were smoking than in 1999.

But are our current tobacco laws strict enough to keep teens safe from the lure of smoking?

By 2021, almost three decades after tobacco laws were introduced in South Africa, about one out of four people between 15 and 24 years were using tobacco, including vapes. (A vape, also called an e-cigarette, is a battery-powered device that heats up a nicotine-containing liquid and produces vapour that is inhaled.)

Moreover, about a quarter of South African university students, aged between 18 and 24 years, vape.

Last week, ahead of today’s World No Tobacco Day, the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a new report detailing how the tobacco industry has used wily marketing tactics to hook the next generation of smokers — including with so-called new-generation products like vapes and nicotine pouches.

Stricter rules, which are, at least partly, aimed at protecting our youth from picking up the tobacco habit, are on the cards. But will South Africa’s new proposed Tobacco Bill — which has been in the making since 2018 — be enough?

Here’s how things have developed over the past 30 years — and what they’re about to become.

A picture’s worth a thousand words

The link between kids seeing ads for tobacco products and lighting up has been shown convincingly and repeatedly in the past. In a 2017 study published in the journal Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 417 non-smoking teens were shown ads for e-cigarettes. Those who saw the ads were more likely to try vapes than those who hadn’t seen the commercials and they felt more positive about the products. This is similar to another study, published 20 years earlier, that found that of the roughly 1 200 school children who watched a cricket tournament where the players were sponsored by cigarette brand Wills, about 8% were either tempted to buy cigarettes or had started smoking, despite knowing about the health hazards.

The new WHO report also zooms in on how social media and streaming platforms are used to make tobacco look cool and how the industry is using these channels for clever marketing, even in countries where tobacco ads aren’t allowed.

On social media alone, content promoting nicotine pouches and e-cigarettes has been viewed more than 3.4-billion times between 2018 and 2023, and in the Netflix series Formula One: Drive to Survive, which follows the off-track drama of racing, tobacco-related branding got a total of 1-billion minutes of airtime globally, research shows.

It’s bad news, a 2020 study across some 14 000 people between the ages of 15 and 21 in the United States found. People who saw images of vaping in programmes on Netflix and cable TV were up to three times more likely to start vaping than peers who’ve not seen such visuals.

These new products are punted as less harmful than conventional tobacco smoking and a way to help smokers quit. Yet they still contain nicotine, which is what gets you hooked and is a gateway to cigarette use. And, evidence shows, packaging products in sleek, colourful wrappers and adding flavours like “Exotic Mango” and “Ruby Berry” make them really attractive to young people.

[WATCH] Will SA’s tobacco laws keep your kid safe?

Why the new Tobacco Bill is necessary

The Tobacco Products Control Act has helped to make smoking socially unacceptable, but, in its current form, it falls short of many of the guidelines set out by the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), like rules about where people can smoke, advertising, packaging and sales. The FCTC is an international agreement signed by 180 countries, including South Africa, and aimed at putting an end to smoking.

- In South Africa, a quarter of the space inside a restaurant, workplace, ship or passenger train can be set aside for smoking. Despite health warnings having to be shown at the entrance of these places, signs like this don’t protect non-smokers from tobacco smoke elsewhere on the premises. For example, a study from Australia showed that in non-smoking areas, levels of nicotine and small soot-like bits in the air were only about half of what the levels were in the spaces where smoking was allowed.

- The FCTC says it’s best to ban all tobacco advertising because partial bans have little impact. Children who see or hear this type of advertising are more likely to experiment with tobacco products, research shows, because using the products is made to look glamorous, desirable and socially acceptable.

Marketing can cross borders easily. Ads can be shown online, in films or in imported print media, and brand names can be displayed on clothing and devices used at sports events or festivals, which may be broadcast in another country.

This FCTC guideline has been one of the most difficult to implement, with only 66 out of the 195 countries surveyed by the WHO blocking all forms of advertising. In South Africa, all ads in local newspapers, magazines and TV or radio broadcasts and sports sponsorships for tobacco have been banned since at least 1999. But as the law stands now, smoking shown in international media and sponsorships is still allowed.

- In the face of tight advertising restrictions, cigarette packaging itself has become a big marketing tool. Brand descriptors and pictures on cigarette packaging can falsely reassure consumers about the potential health risks of the products, research says. For example, brands targeted at young people are marketed as less harsh and include the names of better tasting flavours like “mint” or “strawberry” and colours to make smoking more appealing.

With the new Bill, products like cigarettes and vapes will have to be packaged in plain wrappers, meaning colours, pictures and logos that form part of a brand’s identity will be banned. The minister of health will decide on the material of the package and the font used for the brand name. This type of packaging, research shows, creates negative expectations about the taste of cigarettes. They’re also less likely to be seen as being trendy or popular.

Christina Pitt is a health journalist at Bhekisisa.