- In November 2020, two people were arrested after a consignment of falsified COVID vaccines were discovered in a warehouse in Germiston.

- The World Health Organisation says the global market for substandard or falsified medicines could be worth up to 15% of the total pharmaceutical market.

- Weak medicine regulators in Africa mean the continent is vulnerable to falsified COVID vaccines being circulated.

- Sources at international anti-crime agencies argue that Africa’s strong trade routes with China and India are going to allow criminals to introduce shipments of falsified vaccines into supply chains.

On Friday, 6 March 2020, a day after South Africa recorded its first-confirmed case of COVID-19, and a few weeks after Egypt had on 14 February become the first African country to register an infection, Ugandan police arrested a traditional healer and his daughter in a village 120km east of Kampala.

Police spokesperson, Fred Enanga, told Uganda’s New Vision newspaper: “They visited a number of families … telling them that they had discovered a vaccine for the coronavirus disease … The unknowing subjects purchased the said vaccine at a fee that was negotiated with the seller before it would be administered.”

On 19 November a far more sinister incident unfolded in a warehouse in Germiston, according to Mlungisi Wondo, acting manager of the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority’s (Sahpra) regulatory compliance unit.

The police, he says, tracked “suspicious freight” from the OR Tambo airport to the building east of Johannesburg. After opening a “lot of boxes”, an officer called Sahpra for assistance.

“Our inspectors got there and then they saw prefilled syringes, and they [had labels that] were written in Chinese … The two people who were at the site, the owner of the warehouse and the Chinese owner of the consignment were arrested,” says Wondo.

“There were clear indications that the contents of the boxes were going to be sold as genuine COVID-19 vaccines.”

According to Interpol, the “vaccines” had been advertised for sale on a Chinese social media app, WeChat, and had been imported from Singapore as “cosmetic injections”.

Wondo says the police, in cooperation with Sahpra, are “still trying to trace if there were units released into the country. The risk now is, if people are injected with those [fake] vaccines; we don’t know what is in them because we are still doing the tests at the National Control Laboratory in Bloemfontein.”

On 15 January, Nigeria’s National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (Nafdac) said it was aware of fake vaccines circulating in the country. The agency’s director-general, Mojisola Adeyeye, told a press conference: “Nafdac is pleading with the public to beware. No COVID vaccines have been approved by Nafdac. Fake vaccines … could kill.”

And on 31 January, a “Dr H. Losho from Lagos”, who also advertises sex toys, clothes and shoes, posted the following tweet: “If you’re interested in 2 shots of Covid Vaccine at 50k each, contact @ad_de_moles. AstraZeneca. Arrives in 2 weeks. You get a card.”

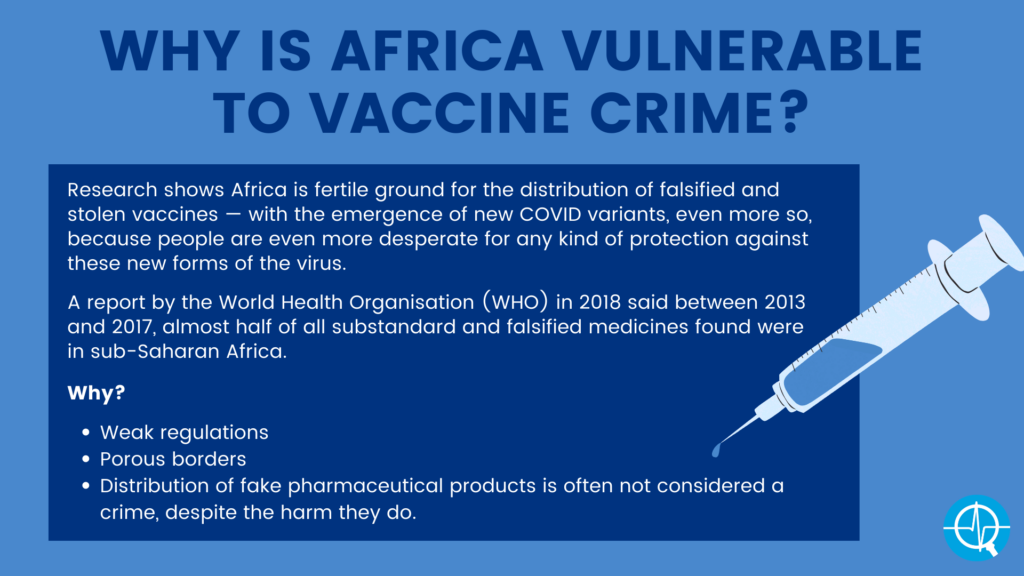

These cases show that Africa is fertile ground for distribution of falsified and stolen vaccines. And with the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) variants, such as the 501Y.V2 variant that was first identified in South Africa, COVID vaccines will become an even more sought-after commodity — because, at least so far, those variants have proven to be more infectious than the original form of the virus. Some are also able to escape the immunity that current vaccines induce, leading to more fear — and desperation — to be protected from such variants by adjusted, newly developed vaccines specific to those variants.

The statistics also show the continent is extremely vulnerable to vaccine crime: A report by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2018 said between 2013 and 2017, almost half of all substandard and falsified medicines found were in sub-Saharan Africa, where regulations are weak, borders porous and the distribution of fake pharmaceutical products is often not considered a crime, despite the harm they do.

“We’ve found very toxic substances in falsified medicines. First, you are not cured, and then you have seen cases of people who are dying because of the product they were taking,” says Cyntia Genolet, the associate director of Africa engagement at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA). The organisation represents the world’s major pharmaceutical firms, including most of those making COVID-19 vaccines.

The WHO report says fake malaria drugs alone cause up to 158 000 deaths every year in sub-Saharan Africa, and that the global market for substandard or falsified medicines could be worth $200bn (about R3-trillion), or 10-15% of the total pharmaceutical market.

Most African countries are unprepared for the potential onslaught of vaccine theft and falsification

In South Africa, one of the African countries worst-affected by the pandemic, the health department says at least 67% of the population of about 60-million must be vaccinated to achieve the herd immunity that would effectively end its epidemic.

South Africa’s vaccine roll-out, that would have started with the AstraZeneca vaccine, was temporarily suspended this week, after new, early data showed that the jab only provides 10% protection against mild to severe COVID-19 caused by the new 501Y.V2 variant.

The health department announced that the country will now, instead, launch an implementation study that will compare how well three jabs — Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer and possibly AstraZeneca — protect against severe COVID-19 disease caused by the new variant. Severe COVID leads to hospitalisations and death and protection against it is therefore an important function of vaccines during pandemics.

And, once the country’s roll-out finally takes off, it will be massive and fraught with challenges.

“This roll-out will be unprecedented in scale, importance and complexity. Will there be crime around that? Probably. But I think we have bigger problems, like how are we going to get the vaccine into the arms of millions of people?” says Salim Abdool Karim, an epidemiologist and co-chair of South Africa’s scientific ministerial advisory committee on COVID-19.

Abdool Karim, who also heads up the HIV research organisation, the Centre for the Aids Programme of Research, Caprisa, adds: “The system that’s going to regulate the vaccines seems pretty strong; they say security around the vaccines will be strong.”

But nowhere close to as strong as in Europe and the United States, where almost every entity involved in distributing the jabs, from airports to transport firms to manufacturers, has formed task teams to keep them safe.

Companies have done background checks on staff; GPS trackers are inside every box of vaccines, which are being stored in secret locations; some vials contain black light verification technology (markings that are only visible using equipment that emits ultraviolet rays) to prevent falsification; some firms are using bogus shipments to throw criminals off-track.

But most African authorities, entangled in negotiations to secure vaccines and preparing for the logistical nightmare of getting them to people across vast territories where transport routes are poor and sometimes non-existent, are nowhere near ready to safeguard the vaccines, according to numerous sources interviewed by Bhekisisa, including law enforcement, crime intelligence, customs and border officials, government representatives and crime analysts.

Africa has almost 1.4-billion inhabitants, according to the latest Worldometers population recording mechanism.

In an analysis in late November last year, the WHO warned that “Africa is far from ready for what will be the continent’s largest ever immunisation drive”.

The analysis found that, based on self-reports by all countries, Africa had an average score of 33% readiness for a COVID-19 vaccine roll-out, far below the WHO’s desired benchmark of 80%.

The organisation said less than half of Africa had identified “priority populations” for vaccination and had plans in place to reach them, and only 44% had “coordination structures” in place.

According to the WHO report, only 24% had “adequate plans for resources and funding”, a mere 17% had data collection and monitoring tools ready, and just 12% had plans to communicate with communities “to build trust and drive demand for immunisation.”

Maurice Ogbonnaya, a crime analyst and former security analyst at the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies in Nigeria’s National Assembly in Abuja, says it’s precisely such inadequacies, “gaps” and disorganisation that could allow organised crime groups (OCGs) to insert falsified vaccines into supply chains, and to steal vaccines.

Why is Africa ripe for a COVID vaccine black market?

Inspired by a sister addicted to illegally trafficked codeine in Nigeria, Ruona Meyer spent more than a year infiltrating gangs dealing in illicit pharmaceuticals in West Africa.

She went undercover as a buyer, her contribution to a Grammy Award-winning documentary in 2018, Sweet Codeine, resulting in several arrests and convictions, including that of a pharmaceutical company executive.

[WATCH] Sweet Codeine

“In Africa, you have all the elements necessary to allow a black market in vaccines to flourish,” says Meyer. “Lack of resources, logistics and technical capacity means it’s going to take incredibly long for the roll-outs to happen. That gives organised crime the time and space needed to strategise, adapt to security measures and to insert their products into supply chains. The poverty and official corruption that’s unfortunately prevalent throughout Africa makes their job much easier.”

In its July 2020 research brief analysing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organised crime infiltration in the legal economy and illegal governance, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC) says: “Although no country is completely immune from fraud, countries with a high level of corruption are at a much greater risk of being affected.”

Meyer adds: “It also doesn’t help that healthcare workers in Africa, many who are going to be in charge of vaccine supplies, are very poorly paid … Of course criminals will take advantage of this.”

Interpol East Africa crime intelligence analyst, John-Patrick Broome, says OCGs are “ideally placed”, having “well-developed networks and methodologies” to smuggle falsified, substandard and stolen vaccines.

“Illicit medications are primarily entering the market in eastern Africa through three key areas. There’s the avoidance of regulations, there’s violence-based criminality and there’s corruption … at a number of different levels,” explains the former British Isles border policing officer.

“The organisations in eastern Africa that have responsibility for regulating the legislation and enforcement activities around this form of criminality have been seen to lack some of the autonomy and powers that they require to deal with the illegal trade.”

Meyer says rising infections and deaths and third and even fourth waves of COVID-19, could cause increasing fear, thus driving demand for vaccines up even further.

“At certain stages supplies will be low. This is the gap that the criminals will fill. We’ve seen it happen already with personal protective equipment (PPE) and chloroquine, when the crime groups got their fakes into global supply chains quite easily.”

Demand for chloroquine, a medication used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, the autoimmune disease lupus erythematosus, and also malaria, rocketed after a French microbiologist claimed in March 2020 it was “efficient” at combating COVID-19.

Former US President Donald Trump also began touting a form of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, as a potential cure, even though there was no evidence to prove that the drug could either treat or prevent COVID-19.

[WATCH] Should doctors prescribe chloroquine to COVID-19 patients?

In the months that followed, Voice of America reports, authorities throughout West and Central Africa seized large quantities of falsified and substandard chloroquine. Many of the tablets were compressed chalk. Police in Cameroon raided and shut down several pharmaceutical manufacturers who were producing fake chloroquine. There’s currently also immense international demand for the anti-parasitic drug, Ivermectin, which is being promoted by some in the medical community as prevention of and treatment for COVID-19, although there is no credible evidence to substantiate these claims. Nevertheless, seizures of illicit Ivermectin are occurring around the world, including in South Africa.

Mafia groups are moving illicit vaccines throughout Europe — and cooperate with criminal enterprises in Africa

Lawyers Marius Schneider and Nora Ho Tu Nam, who advise some of the world’s major pharmaceutical companies on intellectual property issues, warned of the probability of the distribution of fake COVID-19 vaccines on the continent in a report published in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice in May 2020.

“Why are we going to have an issue with the vaccines? Well, it’s very easy: Because the demand will be high, access will be limited, everybody will want to have his shot, and in that kind of situation this vaccine is liquid gold, as it has been called by some, for these criminal syndicates. They will exploit the situation by either stealing the vaccine, or by counterfeiting it,” argues Schneider, a former chairman of the anti-counterfeiting committee of the European Community Trademark Association.

The advocate, originally from Belgium, founded the IPVocate Africa law firm in Mauritius in 2012 to focus on the “severely neglected” areas of protection, management and enforcement of intellectual property rights in Africa.

Schneider’s practice sometimes coordinates anti-counterfeiting raids with law enforcement agencies and represents pharmaceutical multinationals in legal cases.

“We have seen instances where non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been engaged in the distribution of these [falsified] vaccines. These NGOs had as a mission to distribute real vaccines to the people. Employees on the ground in African countries were implicated in vaccine trafficking,” he says.

The IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science calculates global spending on pharmaceuticals in 2019 at $1.25-trillion (almost R18.7-trillion). It projects that the global pharmaceutical market will exceed $1.5-trillion (almost R22.4-trillion) by 2023.

Big money equals big crime, says Ho Tu Nam.

In September 2015, a UK court jailed two former United Nations (UN) consultants for rigging a contract for life-saving drugs between a Danish pharmaceutical firm and government officials in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Guido Bakker and Sijbrandus Scheffer took a bribe of £650 000 (about R13.2-million) to secure a £66-million (about R1.3-billion) tender.

“OCGs have always been interested in pharmaceuticals because of the high profit margins and low risks involved,” says Mark Micallef, North Africa and the Sahel Observatory director of the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime. “They move wherever the greatest profits are to be made at a specific time, therefore it is quite obvious they will get involved in whatever ways they can in the vaccine supply.”

Much of Schneider’s career has focused on organised crime. He participated in the famous “Gomorra” investigation in the 2000s that exposed the sale of counterfeit power tools in Europe, which resulted in the downfall of several figures in the Naples-based Camorra mafia.

“The Camorra had set up production of the tools in China,” Schneider recalls.

The UN estimates in a 2019 report that 75% of falsified and substandard medicines in the world originate from China, Africa’s biggest trade partner, and India, with which the continent also has close relations. The world’s largest vaccine producer, the Serum Institute of India, is already manufacturing COVID vaccines for the drug company AstraZeneca and China has at least three vaccine candidates, two of which are already in distribution.

The UNODC says Italian and Sicilian mafia have for decades trafficked in falsified, substandard and stolen pharmaceutical products, mostly sourced in Asia.

A senior police investigator in the UK, who asked not to be named because he’s not authorised to give information to the media, told Bhekisisa in early December: “The mafia are moving illicit vaccines in locations throughout Europe.”

He confirmed links had been established between these mafia groups and “criminal gangs in Nigeria, Morocco, Egypt and Ivory Coast”. The Camorra mafia, for example, have also been active in South Africa. In 2014, five Italian nationals linked to it were arrested near Port Elizabeth and charged with trying to sell counterfeit power tools worth millions of rands, IOL reports.

Well-established Tramadol routes are “waiting to be fuelled” with fake vaccines

Sources at international anti-crime agencies argue that Africa’s strong trade routes with China and India are going to allow criminals to introduce shipments of falsified vaccines into supply chains.

The 1-million AstraZeneca vaccines that arrived in South Africa on 1 February, came via India from the country’s Serum Institute.

On Sunday, the health department also announced that South Africa is in talks with a Chinese company, Sinopharm, with regards to their COVID jab.

Bhekisisa has spoken with a former trafficker of illegal pharmaceuticals in West Africa, who now assists authorities there with investigations.

He says OCGs are “simply waiting for chaos, desperation and no organisation” in vaccine roll-outs before distributing falsified vaccines, or stealing the genuine product.

“Their networks are activated. They will use the same networks, the same corrupt officials that they are using (for other illegal products). They have the printers and the packaging they need.”

Says Meyer: “There have been cases in which employees of pharmaceutical manufacturers sell genuine medicine packaging to criminal groups.”

The ex-trafficker speaks of a “well-established route for [illegal] tramadol [a pain reliever]” between Nigeria and India “that is waiting to be fueled with (fake) vaccine”.

He says links exist between “front companies in Nigeria and their partners in India so they will try to replace tramadol with COVID vaccines because the money to be made is much more. We talk here of one 1000% plus profit on a vaccine”.

(Pic credit: Nyani Quarmyne, Mosaic)

He scoffs: “I’m sure in some cases the police and soldiers are going to be protecting bad [falsified or stolen] vaccines.”

Micallef collects his information about trafficking of falsified medicines in North Africa from a network of 160 field monitors in Algeria, Chad, Libya, Morocco, Niger, Sudan and Tunisia.

“Fake vaccines; I think there’s a big danger of that,” says the analyst. “In the Maghreb itself, so unregulated territories in Libya, definitely. But also in Tunisia and maybe border areas of Egypt, less so in Algeria, perhaps, but especially in the northern Sahel.”

Micallef says OCGs dealing in falsified vaccines exploit gaps in health services and this will be especially true of COVID-19 shots, which is going to make the crime very difficult to control.

“This form of trafficking … is tapping an actual health sector need. And the fear is that in the case of the vaccines a similar scenario might unfold where there are shortages, especially in the (Sahel) border areas, that are preyed upon by criminal enterprise trying to fill that gap.”

In West Africa, vaccine roll-out is set to happen at a time when regional governments, especially Nigeria’s, have been cracking down on tramadol trafficking. Between 1 and 19 June last year, the Nigerian Drug Law Enforcement Agency and the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control seized illegally imported containers of the drug worth more than 300-million naira, reports Enact, an organisation that works to combat organised crime in Africa.

According to the former trafficker, this crackdown is providing an additional incentive to OCGs in the region to turn their attention to dealing in falsified COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior security official in Nigeria, who requested anonymity, says criminals in India have been “rebranding and renaming” tramadol to import into the country “as something harmless … The concern is they will do similar with COVID vaccines”.

Ogbonnaya says many parallels can be drawn between tramadol trafficking in West Africa and the “likely” illicit trade in falsified and stolen coronavirus vaccines.

“It boils down to weak regulation by state regulatory agencies; it boils down to corruption by those who are saddled with the responsibility of ensuring that the regulations are put in place. It also boils down to a complete absence of a continent-wide regulatory framework.”

Many African countries don’t have medicine regulators, making it easier for criminals to operate

The IFPMA supports “regulatory harmonisation” in Africa, in particular via the Africa Medicines Agency (Ama). According to a press release issued by the African Union in February last year, the Ama is “a proposed specialised agency of the African Union intended to facilitate the harmonisation of medical regulation throughout the African Union”.

“There are so many elements that will make Africa more vulnerable during this time of the vaccines being distributed,” says Genolet. “The weak regulatory system is also something that’s been identified by the WHO.”

Africa isn’t alone in this.

According to a WHO report, globally only three out of ten countries have medicine regulators that function “according to acceptable standards”. “Many African countries don’t have [functional medicine] regulatory systems [such as South Africa’s Sahpra] at all. That’s very important to make sure that medicine that enters a country is safe, and that you can also control what happens after the medicines enter a country.”

The WHO says there are 54 regulatory authorities for medical products (NMRAs) on the African continent, but there are “varying degrees of capacity among them”.

Only one NMRA in sub-Saharan Africa — Tanzania’s — has been formally assessed by the WHO. In 2018 it gave the East African country’s regulator a maturity level 3, the second highest on the WHO’s scale.

Andy Gray, senior lecturer in pharmacological discipline at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s school of health sciences, says previous WHO reports have not identified which African NMRAs “were acceptable and which were not, due to political sensitivity, and the assessment has not been updated. The more mature are certainly the South African, Zimbabwean, Kenyan, Tanzanian, Ghanaian, and Nigerian agencies”.

Gray, who’s also part of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Pharmaceutical Policy and Evidence Based Practice, adds: “There is some capacity in Uganda, Botswana, Namibia and Zambia. I’m less sure of the Francophone countries, but would expect some capacity in Senegal and Morocco, and perhaps Cameroon, but the ties with France are tighter, and so is reliance on their approved products.”

Gray says it “does not sound far from the mark” to say that only 10% of African medicine regulators have “moderately developed capacity”, with 90% having “little to no capacity”.

This void in medicine regulation, says the WHO, leaves most of the continent exposed to unsafe medical products and “facilitates the proliferation of substandard, spurious, falsely labelled, falsified and counterfeit medical products.”

Genolet says the frequent absence of regulation means medicine supply chains in Africa are “very porous. This means there’s limited control of the supply chain. When you have a lot of middlemen involved, and borders that don’t always have controls, it makes it easy to move counterfeit medicines into and out of countries.

“South Africa has one of the better [medicine] regulatory systems in Africa, but even it has thousands of kilometres of unregulated borders.”

But Sahpra’s Mlungisi Wondo emphasises: “Vaccines that are substandard or falsified will be blocked by our processes at the points of entry. Our controls are very strong.”

He says inoculations could come into the country through four points of entry, depending on their origins: Durban, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth (all by sea and air) and Johannesburg (air).

“Medicines can’t come into the country [legally] without going through one of those points. At those points we have customs and port health officials that have been trained to assess medicines coming in,” Wondo explains.

This assessment is, however, merely of the particular consignment’s appearance, in terms of labeling, relevant registration numbers and attached documentation.

“If the registration certificate of the product is in order, it is released to the pharmaceutical company for eventual release onto the market. Those that do not fulfill registration requirements, the officials refer to Sahpra for further investigation,” says Wondo.

He acknowledges that fake and substandard pharmaceutical products do sometimes “slip through” the checks.

“It will be your smuggling, where people are false declaring, saying it’s clothes, then maybe in the middle of the container they’ll put those boxes of medicines. Those then may go through, because of the false declaration.

“But, with the help of the regulatory compliance inspectors and the South Africa Police Services, we do pick the fakes up inside the country, eventually.”

Vaccine theft, rather than falsified jabs, could be South Africa’s challenge

Gray says South Africa’s reputation is of having a secure medicine supply chain.

But he adds that because Sahpra doesn’t proactively sample the market, relying on good manufacturing practices by pharmaceutical companies and the “vigilance” of their forensic units, it could be missing “problems”.

“If our medicines go across into neighbouring countries, is somebody slipping falsified versions into those countries? We don’t know. Are some of the importers’ medicines that are arriving on our shelves not the ones that we expect to find? We haven’t detected any, but it’s not impossible that they are happening,” says Gray.

Many of South Africa’s vaccines are expected to be made at India’s Serum Institute (SI), which is contracted by the COVAX facility to manufacture vaccines for developing countries.

“The SI is approved by the WHO to manufacture the vaccines, so we know it will manufacture good quality products,” says Wondo.

The SI is acknowledged around the world as a safe and secure pharmaceutical production facility. But, as Ho Tu Nam points out: “Medicines emerging from every manufacturer in the world have been falsified; no one’s immune.”

Wondo responds: “Each batch of vaccines that comes into South Africa will be tested. Either by us, or by our trusted partner countries. [Falsified] vaccines will not get past our systems. We will keep our people safe.”

Although Gray believes South Africa’s “vulnerable in some ways” to falsified vaccines, and “bypassing of normal actors” in the supply chain represents a “very ripe opportunity to bring a totally falsified product into the market”, like Abdool Karim he’s convinced the country will have “much bigger problems” to deal with, such as the transportation and distribution of shots.

He does, however, think that vaccines are at risk of being stolen in South Africa.

“I think we are far more vulnerable than we even know,” says Gray. “We’ve certainly had theft from the provincial depots and we have a lot of theft happening from hospitals. In fact, we’ve had problems with theft on demand, where people just phone in to a member of staff and a box gets packed up for them.”

The potential problems with secure storage and distribution of jabs

In South Africa, like in many other countries on the continent, inoculations will happen at public and private hospitals and clinics, pharmacies, mobile centres and places of work. There might also be larger venues where a big number of people can be vaccinated in a relatively short space of time.

Gray believes these vaccine administration sites will be the most vulnerable points along the distribution chain, because they’ll be under much less scrutiny than vaccine shipments.

Meyer says this will be true continent-wide.

“I’ve got confidence in the African Union getting verified, real vaccines into Africa. After a few initial issues with fake PPE, it did a great job coordinating PPE supplies. Where we’re going to have the problem in Africa is with the distributors; in this case, the ministries of health, the little primary healthcare centres that get it from the ministry of health, and further down the line.

“That’s where we are going to have problems with secure storage; there are not these super-secure storage facilities in most of Africa. That’s where we might have people who steal vaccines, or who might break the content of the vaccine. The same way somebody would take pure kilos of cocaine and they’ll mix it with all sorts of things so they can make more profit.”

In East Africa, Interpol’s Broome says the pandemic’s led to an increase in criminal attacks on medical professionals “due to the perception that they have access to medications of which there’s a large demand of across the region. Doctors have been robbed at gunpoint in the belief that they have this access. Organised crime groups have sought to exploit corrupt medical professionals also.”

Abdool Karim is sure there will be “some” theft related to the vaccine roll-out in South Africa. But he adds: “I can’t see how people are going to really steal vaccines and sell them in the black market. If they do, it’ll be a very small, niche population of the very wealthy who will want to jump the queue. Because everybody’s going to get the vaccine; the government is giving it to everybody for free.”

To stop vaccine crime we’re going to have to boost supply

But free or not, says Meyer, if vaccines are in short supply and infections and deaths are continuing, demand will “skyrocket” and “the door will be open” to theft and the insertion of falsified and substandard vaccines into the supply chain.

“To stop narcotics crime, you cut the supply. It’s going to be the opposite way with vaccines: to stop vaccine crime we are going to have to boost supply. The more legitimate vaccines on the market, the less space that criminals are going to have, the less demand there will be for their fake or stolen products.”

Gray agrees, referring to the beginning of the pandemic when South Africans were encouraged to get flu vaccinations. The state had, however, bought most of the jabs to give to “high-risk” employees in the public sector.

“The private sector was battling to get hold of stock; many patients were phoning around pharmacies; there were allegations that some of the chains tended to get preferential access and independent pharmacies couldn’t get access; everyone was trying to buy something somewhere.”

It’s not hard to imagine this scenario being repeated at some stage during the vaccine roll-out, he says.

“That is a perfect breeding ground for a criminal to step in and say, ‘I’ve got some stock which I can get you, which fell off the back of a truck.’”

This is the second of a three part series investigating COVID-related organised crime, supported by a grant from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC). Read the first piece here.

Darren Taylor is a freelance journalist based in Johannesburg. He is a regular contributor to several African and international news organisations.