- During the pandemic, researchers and academic journals have gone into hyperdrive in order to produce research at an accelerated pace.

- This means some sacrifices have been made when it comes to vetting and checking publications through peer review.

- The peer-review system was already flawed even in pre-pandemic times but the current environment has exposed ways in which bad science can slip through.

“It must be an emergency.”

That’s what most motorists assume when an ambulance zooms by on the highway — and why they’re not that surprised when it happens.

Just the same, it was predictable that research on COVID-19 would stream into the academic publishing sphere when the pandemic started in 2020. People’s lives were at stake.

On the road, speed limits set the parameters of how fast you should drive, but there is a certain speed above the limit that is slightly faster while still being relatively safe.

Excessive speed, however, remains reckless, even for ambulances.

Daredevil drivers are kept in check by traffic cops who help to avoid accidents. Likewise, the peer-review and regulatory review processes in the research world help vet studies that are presented to the community.

The risks of speeding up research without peer-review cops

COVID gave researchers a sense of urgency, says Mitchell Warren, executive director of the US-based advocacy organisation Avac.

“We all wanted a vaccine and so we want to go as fast as we can, but that speed must never come at the expense of the scientific process.”

You can put pedal to the metal on vaccine research and still ensure the safety of the jabs, Warren says.

But only if the peer-review traffic cops are on duty.

Warren explains: “There is a way to accelerate the process without sacrificing safety, ethics, community engagement and rigorous reviews, both peer review and regulatory reviews. As long as those things still happen, we should be able to go fast.”

So what happens if the traffic cops are speeding too?

Enter the Sputnik V vaccine.

The jab was approved and used in Russia’s roll-out before its clinical trials were completed. So there were, in fact, no traffic cops on patrol at all.

“They were short-circuiting a process in an incredibly risky way,” Warren says.

But then, The Lancet, one of the world’s most prestigious medical journals, published a state-funded paper on Sputnik’s phase three vaccine trial, granting the jab a certain degree of credibility.

In the warped and accelerated sphere forged by COVID-19, trust in scientists’ integrity (both as producers and reviewers of research) is paramount.

In this second part of our Sputnik V Series, we look at the risks of speeding up research without the safeguards of a peer-review cop on duty. It turns out, the traffic cops aren’t that great at stopping accidents, and the situation has worsened during COVID.

What is peer review?

Not all journals carry the same weight, that’s why some publications are seen as more credible than others. In the science world, some of the biggest and most influential journals are the New England Journal of Medicine, Science, Nature, and The Lancet.

One thing these publications have in common is that they subject paper submissions to a process called peer review. That means that the research is sent to a group of experts in a particular field (their peers) to assess (i.e. review) the quality and validity of the work being submitted.

Roganie Govender, a speech and language therapist at University College London Hospital, writes for Elsevier that the scrutiny of peers also helps share the ethical responsibility of research which could impact people’s lives. Moreover, she argues, engaging with science as a reviewer helps strengthen your own work and writing.

“It acts as a filter to ensure that only high quality research is published, especially in reputable journals, by determining the validity, significance and originality of the study,” explain a group of researchers in the Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine.

But peer review is far from perfect.

A 2019 study by Elsevier and Sense about Science surveyed over 3 000 researchers across various disciplines to understand how they felt about peer review. It found that 75% of scientists were satisfied with the peer review system, with 90% believing that the process helped improve the quality of the papers produced.

But although the researchers surveyed did not want to completely replace the existing system, they did believe that it had areas that could be improved upon.

One aspect that allows for failings, is that the whole process of peer review is entirely reliant on people, their expertise and their time.

As deputy editor of the South African Medical Journal (SAMJ), Bridget Farham explains: “Peer review is one of the bottlenecks in publishing because it takes time to get papers that have been submitted, peer-reviewed.”

Typically, Farham says, people get two weeks to go through the paper, but even with that time scientists often need several reminders to complete the review. She also points out that often “people just don’t respond to our requests for peer review”.

The range of experts available to a journal depends on the publication’s size and reputation. So a smaller journal will have a smaller pool of researchers to call on to assess potential papers for publication, whereas researchers are more eager to do reviews for more “famous” journals and for high impact publications (where the papers are likely to be shared and cited more often).

How does peer review work?

The formal peer-review process has its flaws, even when there’s no pandemic putting extra pressure on researchers, argues Richard Lessells, an infectious diseases specialist at the KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation & Sequencing Platform, Krisp.

When scientists submit their work to a journal, they will sometimes be asked to suggest a few of their peers to act as reviewers. Lessells explains: “Of course, [researchers] might pick people that they think might look favourably upon [their] science.”

But this is where journal editors come in. Their role would be to evaluate the list of suggested researchers and decide whether to approach others, Lessells says. Not all journals allow researchers to suggest reviewers, though.

Peer review takes place for every article published in medical journals around the world – and there are tens of thousands of these publications.

That means researchers’ inboxes are often bursting with requests to review research – for free.

“The reality is that journals sometimes have to send requests to ten researchers to get one person to accept,” Lessells explains.

Researchers that do accept the offer are doing it for “the good of science” and are signing up to a lengthy process that can take hours.

Once a scientist has agreed to review somebody’s research, there are two main things they would look at.

1. How well is the study designed?

For this, researchers look at the way the study was set up, ranging from the broader aspects of the paper such as its structure and arguments, all the way through to the finer details of the research methodology, how the participants were chosen and how well the intervention (say, a vaccine) is delivered.

Randomised control trials are considered the gold standard of clinical research. In these types of studies, participants are divided into a group of people who get the real intervention, and a group who gets a placebo, or dummy drug. This process is “randomised” so that characteristics such as age or sex are equally represented in each group.

When evaluating a randomised control trial, reviewers will assess how well the “blinding” of the study was conducted. That means they’re evaluating how well the researchers ensured that nobody in the study knew which participants received the real intervention and which ones got a placebo.

This is also called the “internal validity” of a study.

2. How generalisable are the results?

Researchers also look at the “external validity” of a study when they’re assessing its veracity. This helps them decide how confidently the research results can be applied to the general population.

Reviewers will look at the population that was studied in terms of their age, race, gender and health status.

A study conducted only in a group of army personnel, for example, will include quite a narrow population group, Lessells explains. They’ll likely all be of a specific age and health status that won’t represent the general population because there will be very few older people included in the study.

What are the limitations of peer review?

Peer review assumes that in the realm of science, people will check their personal bias at the door, which may not always be the case. This is particularly true in smaller research communities.

Papers go out blind to reviewers, which means they don’t know who the authors are or which institutions the research is coming from. This is to prevent someone from negatively reviewing a paper based on their feelings about the person behind the research.

But in reality, it’s a bit harder to control.

“Because of the tiny academic community in South Africa, people do actually have a pretty good idea of who they’re reviewing,” says Farham.

“The best thing to do is to try and find an independent commentator, which is obviously going to be more difficult in a small environment like South Africa.”

Ideally, journals would hope that reviewers would decline if they know there’s a conflict with the research or person submitting the paper. This could include, for example, if a reviewer had previously published a paper with one of the authors or worked closely with them.

According to Lessells: “There’s only so many people who have the skills and the expertise to review certain science. But if you all know each other, it can become difficult because the journal wants to find people who can be objective and don’t have a conflict of interest.”

Even in these cases though, Lessells believes it is possible to objectively review a paper in tight-knit scientific communities — but it requires reviewers to thoroughly interrogate papers and focus purely on the science.

Says Lessells: “It all comes down to the integrity of the science, the integrity of the authors and the integrity of the reviewers and the editors.”

Things “slip through the cracks” during COVID

In the fast-paced and dynamic space of COVID research, there is often a competitive element among journals themselves.

A health consumer advocate, Hilda Bastian says: “People believe that they should trust those journals, that peer review and editorial control are great and the better and more famous the journal, the higher the quality control.”

Bastian was a founding member of the Cochrane Collaboration, which specialises in systematic reviews of medical research. Systematic reviews are studies which evaluate all the evidence previous research has found when investigating the same topic.

Bastian explains that journals “also want to rush to print with really high profile research that is good for their name and gets them a lot of press attention” which means that they sometimes “cut corners”.

For instance, they may want to be the first to share a breakthrough study or high profile work, such as a vaccine’s trial results.

Locally, the SAMJ adopted a rapid publication model for COVID submissions, says Farham.

This rush, coupled with constrained resources, sometimes came at the sacrifice of peer review.

Farham explains: “A lot of the trust element came from the fact that the people who were submitting [papers] are extremely well-known clinicians and researchers and academics within the country. They’re the people I would normally be asking to peer review articles, so in some cases, I would waive peer review.”

Farham, however, says this mainly happened with correspondence pieces that contained “snapshots of clinical data” and not with research articles (although the SAMJ does not publish clinical trial data).

For the more “serious research”, she says, the peer review was sped up drastically with people given between 36 to 48 hours to look through the submission. Given the circumstances, Farham says, there may have been situations where “you find that little bits and pieces slipped through the cracks”. In those scenarios, people could then submit responding queries in correspondence that the journal would publish.

The issue of things “slipping through the cracks” isn’t limited to just smaller journals, though. Even higher-profile scientific publications have made mistakes in the last two years — with some having to print retractions.

One example of this is The Lancet, the second-ranked general and internal medicine journal in the world.

One of the biggest controversies in the world of COVID treatment last year was the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine.

On 22 May 2020, The Lancet published a study claiming that hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine could lead to heart damage and endanger hospitalised patients. This paper led to the World Health Organisation pressing pause on its use of the drug in its clinical trial assessing various potential COVID-19 treatments.

But two weeks later, the journal retracted the paper.

Bastian says: “When The Lancet publishes these papers [for instance, on Sputnik V and hydroxychloroquine] it appears to have the high-quality stamp on it like it’s gone through the ultimate process. It absolutely hasn’t.”

The Lancet tightened its peer-review process after the retraction was published. The journal now has stricter rules for authors and peer-reviewers. For example, study authors are expected to share a statement that outlines which data will be shared and when. The statement has to include an assurance that more than one author has verified datasets used in the research.

When a study is based on real-world datasets, peer-review protocols at The Lancet now also require that at least one reviewer sees the full dataset being studied. In addition, very large datasets will be reviewed by a data scientist and reviewers are explicitly asked whether they have doubts about the integrity of the research paper.

The Lancet is not the only prestigious journal that has had to withdraw a COVID study.

Research was also retracted by what is considered the world’s leading medical journal, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

On 1 May, the NEJM published a study that claimed the use of certain heart medication called ACE inhibitors — which lowers blood pressure — could reduce risk of death for COVID patients. The paper was withdrawn by the authors just over a month later on 4 June.

In both cases, the authors retracted their papers because the underlying data used in the studies was provided by what turned out to be an untrustworthy source and could not be verified.

Reckless driving: The consequences of speeding up COVID science

These two papers were not alone in their mistakes. As amazing as it is to hit warp speed on the production of scientific information, this unprecedented pace also places strain on an already struggling system.

A June paper in BMC Medical Research Methodology identified common reasons behind retractions as errors in the data analysis or methodology of the studies. But there is also an issue regarding the role of peer review in these times.

The authors point out that in their analysis of eight COVID papers, “one was peer-reviewed in less than three days and the second displayed editorial conflict of interest”.

One of the issues identified in the paper was: “While faster peer-reviewing does not necessarily equate with poorer review quality and faster peer-reviewed time is encouraged at a time of crisis, it remains unclear how thorough the peer-reviewing is and how potential conflicts of interest are handled.”

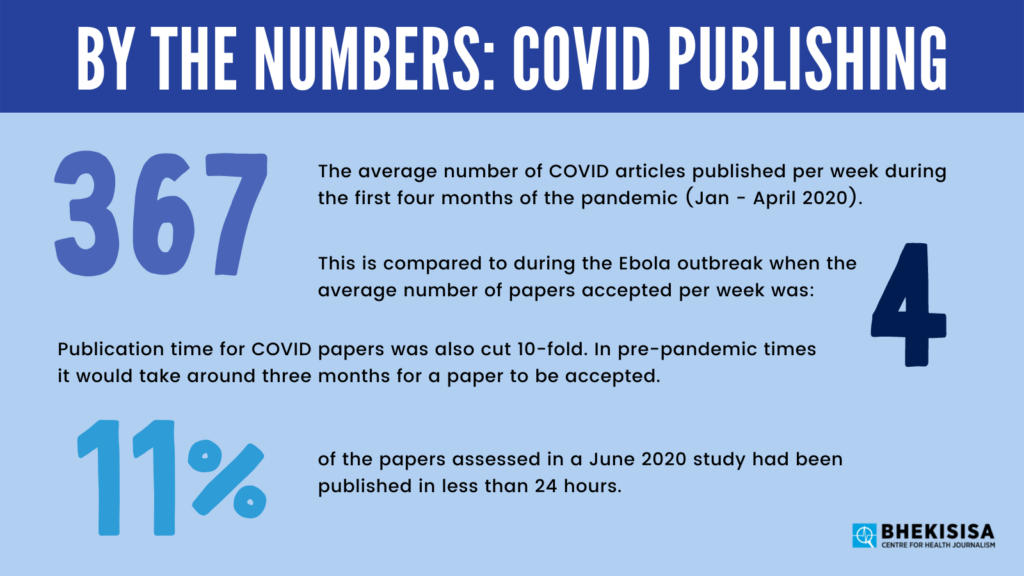

The study compares this to the rate of publication during the Ebola outbreak, where an average of four articles were published per week, taking just over two weeks to be accepted. The rate at which papers were reviewed and accepted during the COVID pandemic was also substantially faster. In pre-COVID times, the same journals took just over three months to accept papers.

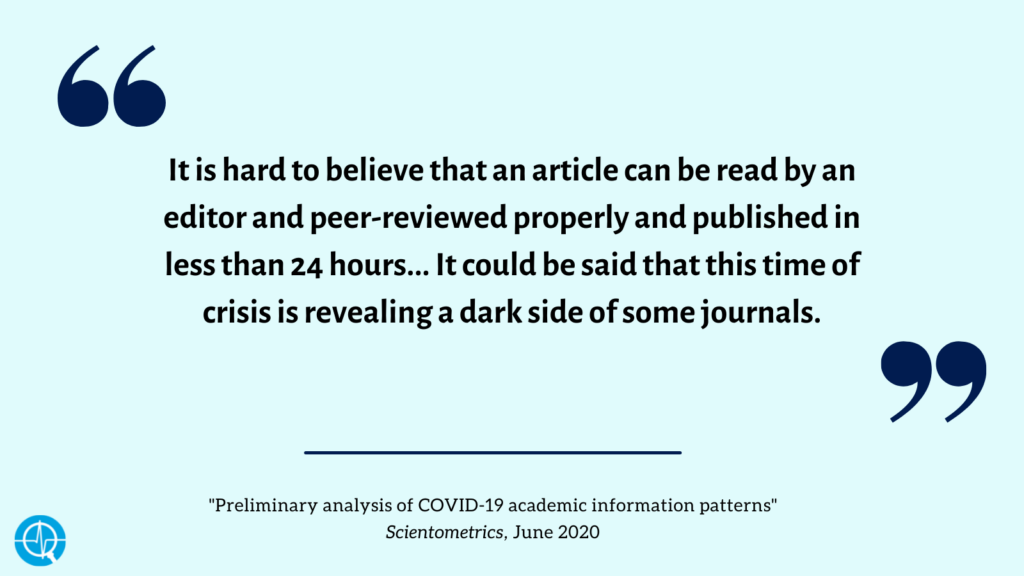

Moreover, a June 2020 paper published in Scientometrics found that COVID had slashed the publication time for papers 10-fold. Worryingly, 11% of the papers assessed had been published in less than 24 hours.

“It is hard to believe that an article can be read by an editor and peer-reviewed properly and published in less than 24 hours,” the paper argues. “It could be said that this time of crisis is revealing a dark side of some journals.”

In their oversight of COVID research, Retraction Watch, an accountability mechanism for journal publications which highlights flawed science and misconduct, identified 132 retracted papers as of 10 August.

Although 17 of the 132 papers were shared as preprints or in other formats (like presentations) that had not undergone peer review, 87% of the studies were published in journals that supposedly vetted the work.

Retraction Watch found 13 of the 132 retracted papers (or one out of every ten papers) were published in journals which are regarded among the top 10% of global academic journals by the research database Scopus. Among these journals, five of the retractions were from The Lancet. In 2019, the journal retracted two pieces — one of which was a book review.

Retractions of COVID-19 research in journals were more than three times as high as retractions of research about the H1N1 (swine flu) outbreak in 2009, found a June study published in Accountability in Research.

Where does Sputnik V come in?

The Sputnik V vaccine trials have been afforded credibility by having results published in The Lancet.

Barry Schoub, who heads up the ministerial advisory committee on COVID-19 vaccines argues there’s only so much journal editors can do with the data provided.

He explains: “I would more or less trust the high citation journals such as The Lancet, it’s one of the oldest medical journals. Their scientific integrity is pretty good.”

But even so, the trial is shrouded by a litany of concerns and red flags:

- The study design wasn’t public.

- There wasn’t proper reporting of adverse events or side-effects.

- There was a lack of diversity in the trial’s participants.

For more detail on these issues, see part 1 of our series

So even without a retraction entering the equation, there are serious questions about the underlying data used in the reported results of the Sputnik study, some of which may have passed through peer review.

The fact that most research papers are not retracted doesn’t mean they’re without error, a 2019 study published in the journal Trials found.

The researchers, led by Bad Science author Ben Goldacre, monitored all the trials reported in five prestigious journals over a six-week period. The journals included the New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association, British Medical Journal, and Annals of Internal Medicine.

All the publications endorse guidelines designed to combat bad reporting on randomised clinical trials, called Consort (an acronym for Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials).

Using the Consort guidelines, the researchers assessed the published journal reports against the study protocols and entries on trial registries.

They were looking for misreported trials, and that’s just what they found.

Not only did all five journals flout Consort’s rules, the journals mostly rejected correction letters sent by Goldacre and his colleagues which pointed out the errors.

Nearly 90% of trials assessed required a correction letter, but fewer than half of the letters sent were published by journals — and the corrections that were published only saw the light about 99 days later.

[WATCH] In the science kitchen: Making the perfect burger

An increasing reliance on preprints

At the forefront of all of this is the reminder that peer review isn’t perfect. As with the people upon whom the process relies, it has its flaws.

It’s the simple truth of the matter: People miss things. It doesn’t matter how much time you have or how carefully you pore over the study, sometimes mistakes still slip through.

That’s why more eyes always help.

The more people who are able to look at a paper, assess it and give their input, the better.

A May paper in Science Progress notes that the scrutiny of other scientists provides a fail-safe for the review process. The authors write: “The retracted Lancet and the NEJM papers failed at the peer review level; however, scientific community attention captured the errors in record time.” This is what led to the short time it took for the papers to be retracted.

Under COVID, the publication of preprints has — counterintuitively — allowed for more scrutiny.

Preprints are when scientists choose to share their research, in the form of a draft paper, with the public without it needing to undergo peer review. Often with COVID papers, research is first shared in this way and then submitted to a journal in order to avoid delays in getting the information out.

Through social media platforms such as Twitter, preprints about COVID treatments and vaccines are put in front of far more expert eyeballs than they otherwise would have been, which can help researchers improve the paper they eventually submit for peer review.

Krisp’s Lessells explains: “It’s clear to me that preprints are a good thing.”

Of course, bad science may be published this way, but Lessells cautions that bad science slips through the formal peer-review process too.

“The more people see your work the higher the chances are that bad science will be flagged as such.”