- About 500 scientists in 30 African countries have been tracking the evolution of over 100 diseases on the continent.

- These efforts were ramped up during the COVID-19 pandemic to help governments make public health decisions.

- There are still problems such as the time it takes to get samples to far-away sequencing centres or a shortage of reagents required for transport or analysis, that need to be addressed to help Africa prepare for future pandemics.

In October 2020, South African scientist Tulio de Oliveira and his team, sequencing coronavirus samples at their lab in the eastern coastal city of Durban, were the first to detect the Beta variant — also called B.1.351 — of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

“We immediately informed our ministry of health and our President Cyril Ramaphosa when we discovered the Beta variant in South Africa very early in our second wave (of SARS-COV-2 infections),” said de Oliveira, a bioinformatician who has become a familiar face on South African television during the pandemic.

Within a day, new legislation was drafted, putting the country into a stricter level of lockdown. “It took less than 48 hours of knowing about the new variant to do that,” he said.

De Oliveira is the director of KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform (Krisp) and the Centre for Epidemic Response and Innovation (Ceri), part of a network of scientific institutions in South Africa established in June 2020 to ensure the public health system had access to the best possible scientific data about the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

In the last week, De Oliveira’s name has again been splashed across international media, this time because of the discovery of the Omicron variant. As part of the Network for Genomic Surveillance in South Africa, a collaboration of laboratories, scientists and academic institutions, De Oliveira reported that a new variant with a “constellation of mutations” had been identified in samples sequenced in South Africa’s Gauteng province, which is experiencing an uptick of COVID-19 cases.

Omicron has already spread across the world. Scientists are urgently working to determine how transmissible and deadly it is, and whether it may be able to evade the protections of current vaccines.

The work of De Oliveira and his colleagues has highlighted the critical importance of genomic sequencing, a process that identifies the genetic structure of the virus and enables scientists to identify mutations – allowing governments to make quick and informed public health decisions.

In Africa, there are over 500 scientists working in 30 countries on genomic sequencing, according to the South Africa-based Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) initiative, which aims to create and support a pan-continental network of laboratories conducting research in genomic sciences.

But the continent lags far behind the rest of the world when it comes to sequencing, said Matshidiso Moeti, World Health Organisation (WHO) regional director for Africa. “Only 1% of over 3-million COVID-19 sequences conducted worldwide occur in Africa,” she said in September.

“Countries must step up surveillance because without genomic information, variants can spread undetected. You can’t fix what you don’t measure.”

An evolving virus: How to spot when a variant is a problem

Like all viruses, SARS-CoV-2, mutates or changes as it spreads. Some mutations do not change the virus very much, but some may make it more contagious, or affect the performance of vaccines or how serious the disease is that the virus results in.

When scientists note that a mutation has genetic changes that could predict faster transmissibility or increased virulence, the WHO designates it a variant of interest.

There are several variants of interest circulating around the globe. The WHO has identified Lamda (first detected in Peru) and Mu (first detected in Colombia); while the Africa Centres for Disease Control (Africa CDC) is monitoring Eta, also known as B.1.525 (first sampled in the UK), and A.23.1 (first detected in Uganda in October 2020).

A variant of interest becomes a variant of concern when the mutations make the germ (in this case, SARS-CoV-2) more transmissible, change the clinical disease presentation (e.g. causes more severe disease) or decrease the effectiveness of public health measures to control the virus – for instance, if the variant reduces the efficacy of vaccines.

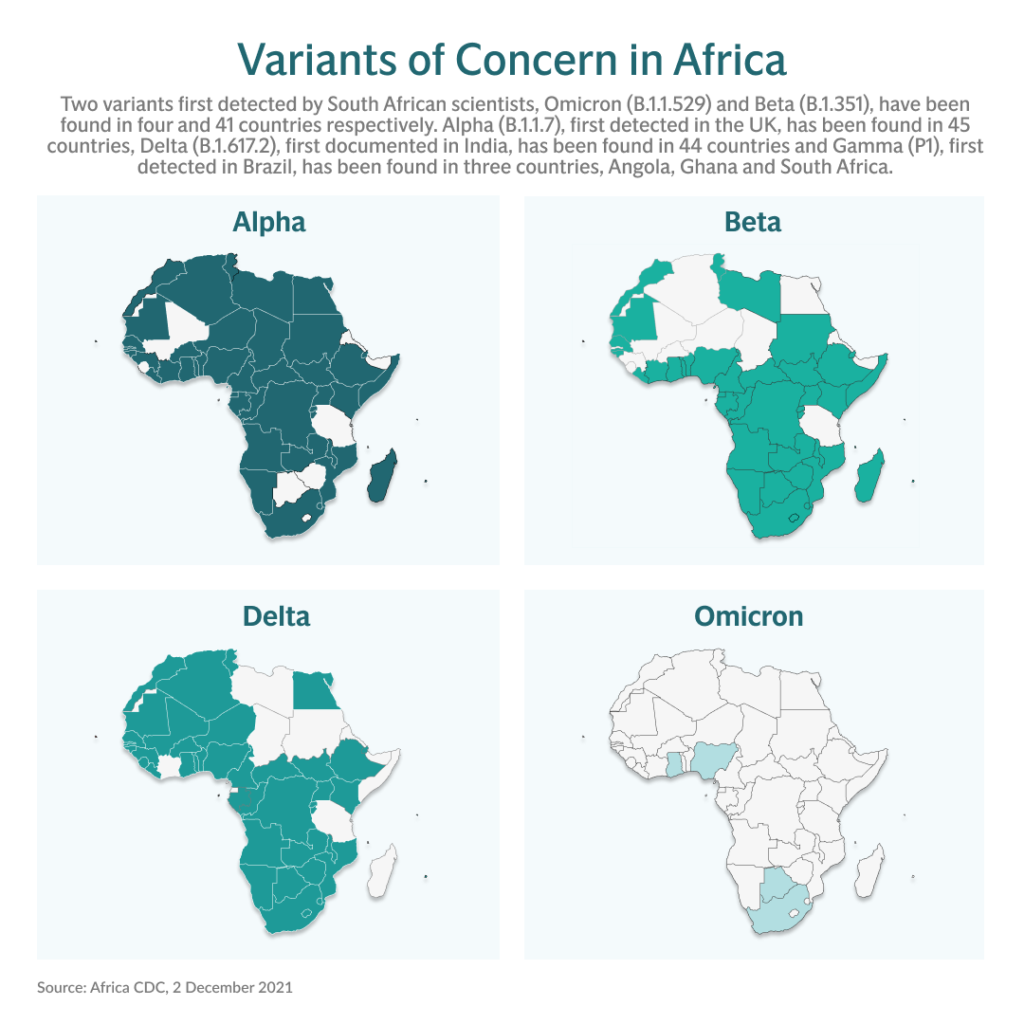

There are four designated variants of concern: Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta. All four have been found in Africa, with Delta, or B.1.617.2 being the main form of the virus circulating on the continent at present.

According to Nicksy Gumede-Moeletsi, virologist with the WHO Regional Office for Africa, there is “serious concern” related to the Delta variant because, although responsive to vaccines, once it rears its head it seems to dominate over other variants.

The virus trackers: How Africa is ramping up its genomic surveillance

Genomic sequencing is not new to Africa and is already well established for other viruses. “The African continent is dealing with in excess of 100 diseases per year,” said Alan Christoffels, the director of the South African National Bioinformatics Institute, one of four specialised genomics and bioinformatic centres in Africa.

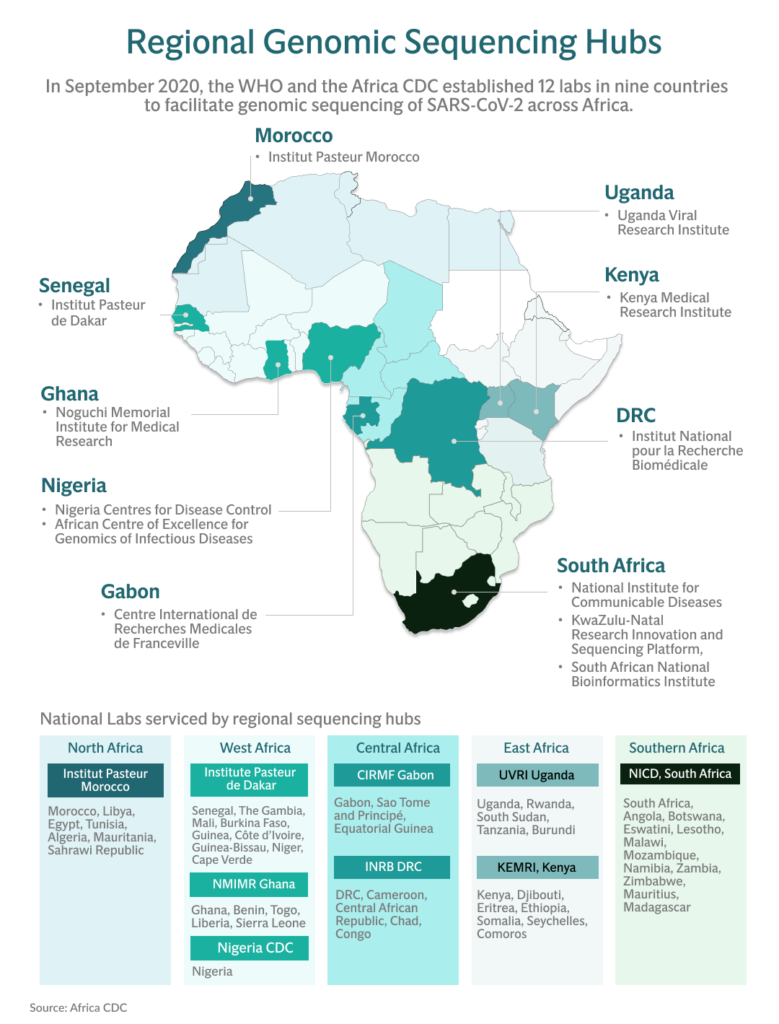

The other three centres are the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases in Nigeria, Krisp in South Africa, and the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya, plus nine regional sequencing hubs from Morocco to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to Uganda.

Each region is affected by different viruses. For instance, in South Africa, the focus has been on sequencing the tuberculosis bacterium and HIV. The DRC has been sequencing haemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola and monkeypox, the poliovirus and the plague. Uganda has been sequencing viruses such as rift valley fever.

The coronavirus pandemic has turned a spotlight on genomic surveillance and its crucial value in identifying variants quickly, tracking their transmission around the globe and helping governments to make quick public health decisions.

In September 2020, the 12 existing sequencing laboratories were launched by the WHO and the Africa CDC as a network to ramp up sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on the continent.

“The aim of this network is to go beyond COVID-19,” said Gumede-Moeletsi. “Meaning that we are more than ready for any other pandemic that might hit our continent because we’ve got well-established sequencing laboratory networks that are focusing on any emerging pathogen.”

The networks are based on three tiers, said de Oliveira of South-Africa’s Krisp and Ceri: specialised genomic centres (such as Ceri and Krisp), regional genomics facilities and national laboratories.

“African countries should make efforts to be as active as possible at all three levels. This not only boosts genomic sequencing data but really facilitates the transfer of knowledge and training – which is important for sustainability,” he said.

Mind the gap: How sequencers are trying keep pace with COVID on the continent

Countries are already building capacity, some with help from established sequencing centres such as South Africa. In all, 32 countries in Africa now have genomic sequencing projects, according to the World Report, a database of funded biomedical research across the globe started in 2012 by the US government’s National Institutes of Health.

But there are gaps in capacity across the continent. For instance, a sample could be taken in Muyinga, a city in northern Burundi, and then has to be sent 97km to the country’s capital, Gitega, before it can be delivered to the closest genomic sequencing centre, the Uganda Viral Research Institute, for testing.

“We still have areas that when shipping the samples to wherever it is supposed to be tested is still taking a serious number of days before it reaches the laboratory itself. And, as such, we are not getting the report as soon as we were expecting,” said Gumede-Moeletsi.

The lag is not only affected by the time samples spend in transit to the lab, but also by the lack of reagents because of supply chain disruption, scarcity of skills, and “hesitancy of some health officials to release data”, according to a research paper in the journal Science.

The technology is expensive. And specialists in bioinformatics and genomic epidemiology are relatively rare in the public health sector, research published in Nature Medicine found.

With the end of year holidays nearing, it is a critical time for the march of the virus in Africa, where only 6.5% of people had been fully vaccinated by November 20.

“It’s not the disease that moves, it is people that are moving.

“We are starting to see that the well known variants are even moving ahead in having further mutation(s) in certain areas that might cause a danger to our society,” said Gumede-Moeletsi.

But there is hope.

“Genomic surveillance is advancing quite fast in Africa and has grown considerably this year,” said de Oliviera in early October. “At the beginning of the year, we had not even reached 10 000 genomes.”

Now that figure stands at more than 50 000.

This story is part of the Vaccine for the World series from the Evening Standard in London.

[This article was updated on 2 December to reflect the discovery of the Omicron variant.]