- South Africa now has 51 confirmed cholera cases — one in Limpopo, six in the Free State and 44 in Gauteng — and 23 people have died of the disease.

- In Hammanskraal (near Pretoria) alone, 48 cholera cases had been confirmed by 6pm on 27 May. The Gauteng health department has set up a field hospital, consisting of six tents, at Kanana in Hammanskraal for people with symptom of dehydration, vomiting and diarrhoea.

- Almost every single case of cholera in South Africa is someone who lives in an area with no or little running water — or contaminated running water — and far from adequate toilets. Why? Read our past reporting.

- Click here for information from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases about how the bug spreads or watch our video to find out how to protect yourself from infection.

- We’ve boiled down the health department’s three-hour cholera outbreak webinar on Tuesday into a simple Q&A. Watch the webinar here using the passcode: L@6n!=#k. Catch up on our live tweets below.

[WATCH] How does cholera spread? Find out

How South Africa’s cholera outbreak exposes unfit municipalities: Read Mia Malan and Joan van Dyk’s op-ed in our newsletter here.

The basics

When is someone “suspected” to have cholera?

Anyone who is ill, or has died because of watery diarrhoea should be seen as a “suspected” case of cholera. People with the condition may have the runs three or more times a day. Stools may be watery or slightly slimy, but should not have any blood. Watery diarrhoea usually lasts less than seven days.

Health workers are legally obligated to report all suspected cases of cholera to the national health department. Here’s the form to use.

When does someone definitely have cholera?

Cholera must be officially confirmed in a laboratory, but health workers shouldn’t wait for the results to get back before treating patients, warned Juno Thomas, who heads the team at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) that’s investigating the outbreak.

How should health workers collect a sample?

A stool sample is best, but if it’s impractical to do this (for example, in a baby, if the stool is too watery, or if there’s no stool at all), a rectal swab could work too. Here’s how to give lab technicians the best chance to detect cholera if it’s there.

Who will do the lab tests?

The test for cholera is available in all microbiology labs in the public and private sector, Thomas says.

Government clinics and hospitals that have a National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) facility on site should take specimens to the lab immediately, by hand, in a container clearly marked “suspected cholera”.

Thomas asked health workers to be patient, since cholera tests take a while to do. The first step of the process, in which laboratory staff see whether the sample will cause any bacteria to grow on a gel in a petri dish (a small transparent saucer-like dish), can take up to 18 hours. Cholera bacteria grow best when they get air, so the dish is sometimes also put in a machine that shakes it around.

Facilities that don’t have on-site NHLS labs should also try to get cholera samples analysed quickly.

All positive cases of cholera have to be sent to the NICD for confirmation, but the Institute doesn’t have enough staff or equipment to do all the initial tests as well, Thomas says.

Are there rapid tests available?

No, South Africa’s state facilities don’t have rapid tests. But, Thomas says, they’re not a good way to find cholera cases anyway because they’re not sensitive enough, which means some people who are ill will be sent home without treatment.

Tips for spotting cholera early

How will you know when somebody could have cholera?

Most people who are ill with cholera won’t look or feel very ill, explained Jeremy Nel. He’s an infectious diseases expert at the University of the Witwatersrand.

However, doctors who are used to treating adults should remember that watery diarrhoea is rare in adults, so this would be a strong sign to suspect cholera infection.

“Rice water stool” is another warning sign. This is when someone’s stool is the milky colour of water that runs off cooked rice. This is a sign of someone already being very ill, and needing help urgently.

The rehydration robot

Once you’ve established that a patient may have cholera, you need to treat them based on how dehydrated they are.

It’s useful to decide whether the status of dehydration is red, orange or green, like a robot.

Severe dehydration:

- The patient is sleepy or unconscious

- They have no or only a weak pulse

- They’re struggling to breathe

- At least two of these signs:

- When their skin is pinched, it takes long to fall back

- The patient can’t drink water or drinks poorly

- The patient’s eyes looked sunken

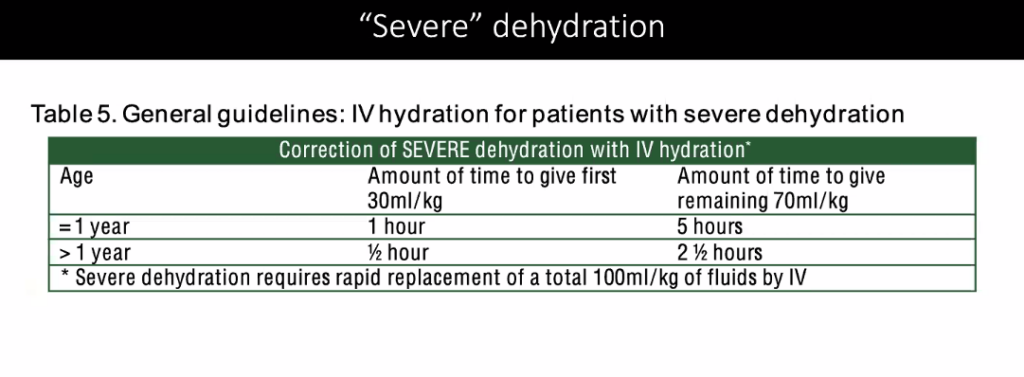

People who are severely hydrated must be put on a drip with a medicine called “Ringer’s lactate”, which is a stronger version of a common rehydrating solution.

The dosages for adults and children are here.

In the case of mild dehydration, a patient would show at least two of these signs:

- Being irritable or restless

- Pinched skin falls back slowly

- Extreme thirst and drinking water eagerly

- Fast pulse

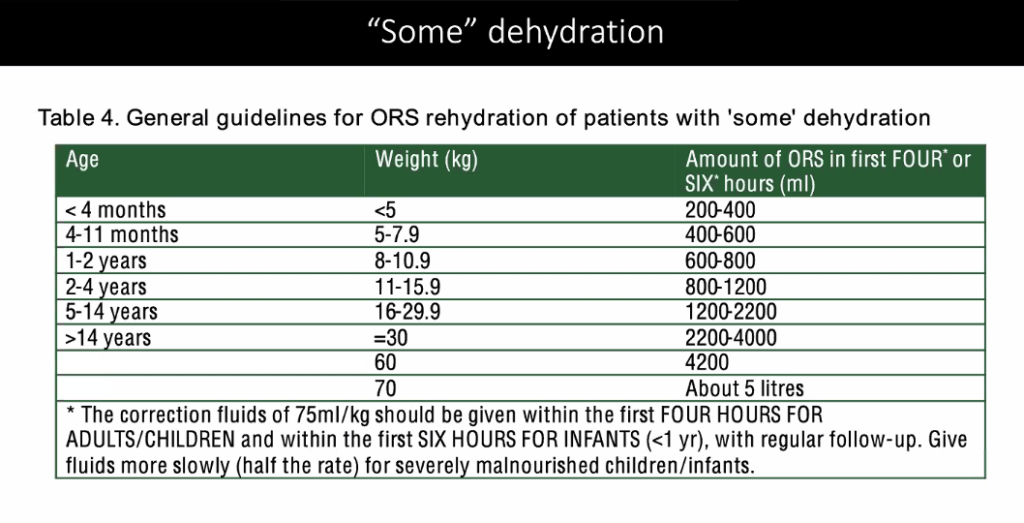

People who are mildly hydrated should be given rehydration medicine by mouth according to their weight and age. Details here.

After four hours, health workers should see if the treatment is helping. If it’s not, the patient should get antibiotics or a Ringer’s lactate drip. If they’re getting better, health workers can consider moving them into the “green” category, which means they could be considered for discharge.

No dehydration:

- The patient is awake and alert

- They have a normal pulse

- They aren’t abnormally thirsty

- Their eyes aren’t sunken

- They pass the skin pinch test (the skin goes back to its normal position quickly)

In such cases, a patient should be monitored for four hours.

They can be discharged from the hospital if they:

- can take their rehydration medicine without vomiting

- have not had a watery stool in this time

- can walk without help

- are passing urine (people who are seriously dehydrated don’t urinate often)

Do antibiotics work against cholera?

Yes. The strain of cholera that’s causing South Africa’s outbreak can be treated with an antibiotic called ciprofloxacin, showed the NICD’s analysis.

The Institute recommends antibiotics for patients sick enough to be hospitalised and for people who don’t respond to the oral rehydration treatment after they’ve been monitored for four hours. Pregnant women and those with HIV should also get antibiotics. Patients who pass one watery stool an hour during the first four hours of treatment should also get this medicine.

Children should get a dose of 20mg/kg body weight per mouth in one go.

Adults should get 1g per mouth in one go.

Rapid fire tips

- Feed patients as soon as they’re fully conscious and able to eat.

- Children under the age of five should be given a zinc supplement (it helps to stop diarrhoea).

- Don’t use medicines such as Imodium to stop diarrhoea. It won’t work and it could make a patient’s symptoms worse.

- People with cholera need far more fluids than you might expect.

How to protect other patients from contracting cholera

If it’s possible, hospitalised cholera patients should use a different toilet from other patients in the facility.