- Agreeing to sex is complex — but it’s not complicated.

- Things like how you grew up, your age, gender, sexual identity and orientation influence how you understand what sexual consent means.

- Experts say saying yes to sex is about desire, communication and interpretation — and both partners have to agree.

- We asked ordinary people in South Africa about their views on sexual consent.

This weekend, people are taking a sho’t left to Gallagher Estate in Midrand, some with coy curiosity, some with boundless excitement, and some in stunned silence.

It’s Sexpo time.

The exhibition is something that gets South Africans talking, whether in hushed astonishment about toys and techniques or with frank openness about orgasms and the basics of what healthy sex means.

A healthy sex life, says the World Health Organisation, is part of our wellbeing, and important for safe relationships too. But for people to have healthy sex, it means we have to tell a partner that we want to do it — or not.

This is called sexual consent, which experts at a webinar hosted by the World Association for Sexual Health (WAS) in September, explained as “essentially giving permission for sexual activity — from kissing all the way to intercourse”.

For the message to get across, relationship researchers say three things need to be in play — and both partners have to be part of the conversation.

- First, find out if you both want to get it on.

- If the desire is there, then you have to tell the other person so, whether through your words or how you behave.

- And then, each partner has the responsibility to pick up on those cues and interpret what the message means: is it a go or a no?

But it’s here where things get murky, because the rules of the society we live in, our religious beliefs, cultural background and things like our age, gender identity and sexual orientation all influence what we think — and how we talk — about having sex.

Researchers call this “sexual scripting”. Much like actors learn lines and actions for their performance, who we are and the environment we live in shape our decisions about what we accept as normal in society and what certain behaviours mean.

And this got us thinking: what does saying yes — or no — to sex mean to South Africans from different backgrounds, and what influences our decisions?

So we asked. Here’s what people said.

1. Sex is taboo — and talking about it too

In school, sex ed lessons often focus on the risks of sex, like an unplanned pregnancy or getting an infection, and so, often, abstinence is taught as the safest way to deal with sex. Despite South Africa’s public school curriculum promoting comprehensive sexuality education, teachers’ personal beliefs can shape what kids learn about sex and how to talk about it.

This, says Jaco Oelofsen, 27, from Cape Town, is how it was for him.

“I went to quite a religious school and the emphasis there was very much on abstinence. Sex was something that wasn’t really spoken about and wasn’t supposed to happen. So by extension consent was not something that was spoken about [either].”

Later, at university and being in an all-male residence, consent was almost just a hurdle to get past, he says — and to his mind, a harmful idea about consent.

2. Someone takes and someone has to give

Saying yes or no to sex is often not an equal power balance. In focus group discussions with 77 teenagers and young adults in England, from different races and spanning different sexual orientations and identities, researchers found that the seemingly more powerful partner could ask for sex easier, while the other generally had to exert their control through refusing sex.

But in many societies this choice is not free and it’s often linked to gender roles, with men being seen as more dominant and women having to be submissive. Results from demographic and health surveys across 27 African countries have shown the more decision-making power women have in their homes, the better they can negotiate how and when they have sex, which means they have more control over their sexual wellbeing.

“I think most men — and even some women — see sexual consent and relationships as one thing, whereas it’s two completely different things,” says Zaakier Yassiem, 26, a gay Muslim man from Cape Town.

3. Consent is complex — but it shouldn’t be confusing

“We speak about consent like it’s a really confusing thing, as if in some instances, someone has rights over another person’s body. That’s never the case,” says Candice Ludick, 41, from Knysna, who works with people who’ve been raped.

Consent has to be communicated, said Terry Humphreys, head of the psychology graduate programme at Trent University, during the WAS webinar. But that doesn’t mean you only have to say yes or no — often body language signals that you want to go ahead or stop. The more intimate a couple’s relationship, the easier they pick up on each other’s cues and the better they know what the other wants or will accept, his research has found.

Gorata Chengeta, 30, a postgrad student from Wits says that she thinks being in a long-term relationship can also blur the issue of consent, though, because “if you’re married or in a relationship with someone, then [there’s this idea] they don’t always have to ask you for consent”.

To her, the situation in which someone agrees to having sex must be clear. “If someone’s being coerced, then it doesn’t count.”

4. Doing it with desire

One of the main ideas of sexual consent is that it has to come from both partners, research shows. And, adds Planned Parenthood, a sexual health advocacy organisation from the United States, saying yes to sex must fill you with enthusiasm. Pleasure is a part of sexual health, and as a previous piece by Bhekisisa says, pleasure can increase sexual agency.

Understanding that agreeing to sex because it’s enjoyable is something Tendai Matsika, 34, from Johannesburg learned only during his university years, he says. “I didn’t learn it in my upbringing — and it was pretty much the same for my peers too.” To him, teaching kids healthy boundaries must be part of how we learn what consent means, he says.

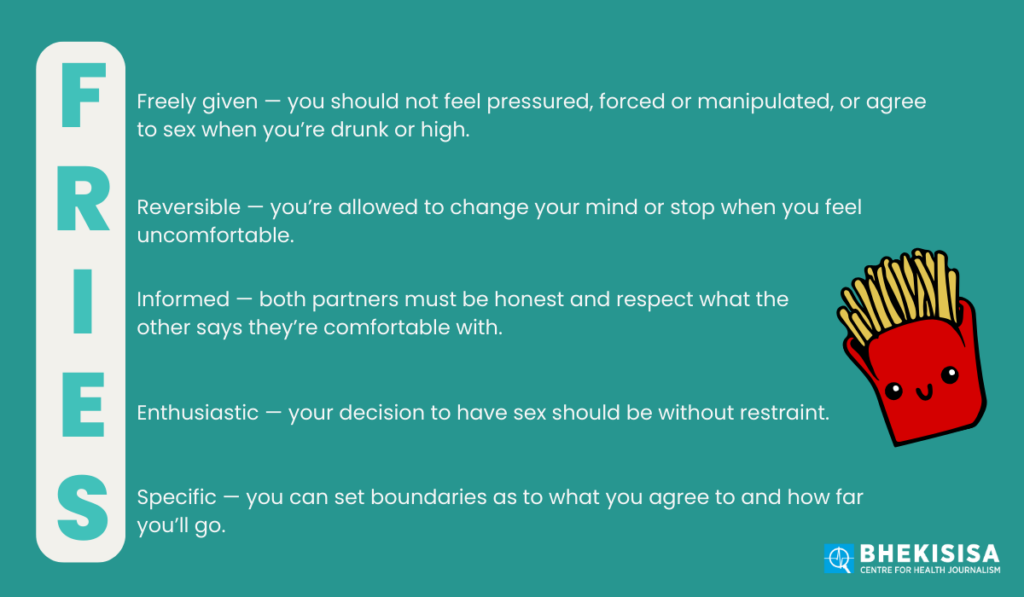

Counsellors use the acronym “Fries” to help people understand what sexual consent means. It says consent has to be:

Lisa Welsh, a sex educator at My Sexual Health, breaks it down.