Health professionals are finding the state’s planned guidelines for fees a bitter pill to swallow.

Doctors’ and dentists’ associations have accused the Health Professions Council and the health minister of having a “hidden agenda” by introducing low guideline tariffs. This, they say, is to “force down” fees to unrealistic levels so that the government’s planned National Health Insurance scheme is able to afford them.

The council, however, has vehemently denied this, saying the allegation has “no basis in fact or truth”. According to Usuf Chikte, the chairperson of the tariff committee of the medical and dental professions board, the council has a mandate derived from the Health Professions Act to set fees that can be used as a normative standard to determine whether doctors or dentists have overcharged patients.

Health practitioners’ fees in South Africa are currently not regulated.

Last year the council published guideline tariffs on its website but retracted the fees soon after when medical associations threatened the council with court action. Doctors and dentists argued that the council failed to consult them when determining the tariffs, that the council did not have a mandate to publish guideline tariffs and that the fees were “unreasonably low” and calculated “without a scientific basis”. On the whole, the tariffs were lower than what medical schemes are prepared to pay.

The council has since opened up the process of determining guideline tariffs for public participation — organisations and individuals have until February 21 to make submissions.

Here is a dummies guide to what the fight is about:

Why does the council want to regulate tariffs?

The Health Professions Council said the lack of tariff guidelines adds to spiralling healthcare costs. According to Chikte, the council regularly receives complaints from patients who claim they have been overcharged.

Some private doctors and dentists charge fees that are as much as five times higher than medical aid rates.

Chikte said the Health Professions Act allows the council to determine guideline tariffs or fees that should be used as the norm when establishing whether a medical professional has “ripped off” a patient. Because there are no guideline tariffs the council has no benchmark fee to use to establish whether a patient has been invoiced an excessive amount.

Do doctors and dentists like the idea of guideline tariffs?

Medical associations have different opinions on this issue.

The South African Dental Association, for instance, rejects the regulation of fees for the majority of dental procedures.

The South African Medical Association doesn’t have an issue with “ethical” or “ceiling” tariffs but does find “guideline” tariffs problematic.

The Private Practitioners Forum argues that the law only allows the council to create “maximum” or “ethical” tariffs that could be used to determine whether a health practitioner has overcharged a patient.

Guideline tariffs, said Chris Archer of the forum, amount to “commercial benchmark” or “medical aid reimbursement” tariffs that, in the organisation’s opinion, would be illegal for the council to create. According to Archer, “ethical” tariffs should be at least 20% higher than “guideline” tariffs.

Although it wouldn’t be illegal for doctors to charge more than the guideline tariffs, doctor organisations argue that medical schemes will gravitate towards these fees.

How did the council calculate its 2012 guideline tariffs?

The council used an inflation-adjusted version of the 2006 national reference price list. This was a guide that was used by the medical schemes industry to determine reimbursement rates. The 2012 tariffs are in effect the 2006 reference list plus 46.66%.

Why don’t health professionals agree with the tariffs?

Doctors and dentists say the council has used the wrong “basis” or “foundation” to work from. They believe that the reference price list was never determined scientifically but rather consists of rates that the medical aid industry arbitrarily decided it could afford based on actuarial analysis of claims patterns.

In the years prior to 2006 the South African medical and dental associations annually calculated what they call “professional tariffs”, which they say the council adopted and published. These rates were significantly higher than those on the price list and were based on the actual cost of medical procedures.

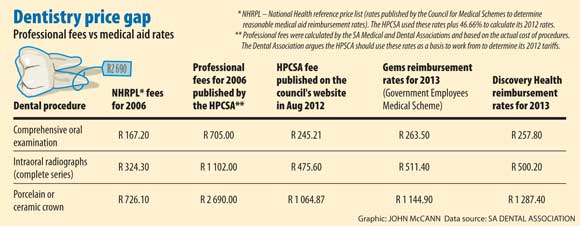

As a result, the dental association said, last year’s dentist fees were on average between 30% and 40% lower than the 2006 “professional fees” and on the whole much lower than what medical aids are prepared to pay (see “Dentistry price gap”).

The tariffs are also all standard fees, which they say fail to make provision for different levels of experience, the inconsistencies in the cost of operating for doctors in different geographical areas (for example, Sandton versus Alexandra or rural versus urban) or the cost of medical technology that better equipped doctors incur.

Medical professionals also claim that the council didn’t consult them when determining the tariffs and has therefore acted “unconstitutionally”.

Why don’t doctors and the government discuss the tariffs?

In short, the law prevents them from doing so. In 2004, the Competition Commission ruled that medical organisations are not allowed to discuss the cost and pricing of services among themselves. According to the commission, this would amount to “collective bargaining” that could lead to “price fixing”.

It’s one of the few issues on which Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi and private doctors agree regarding the pricing of services: that this ruling is standing in their way of coming up with a feasible solution.

Why isn’t there a bid to regulate other professions’ fees?

The private health industry is largely funded by medical schemes as opposed to, for instance, the building industry where clients pay providers directly.

According to Alex van den Heever, Old Mutual chair in social security systems, administration and management studies at the University of the Witwatersrand, this means that the relationship between the consumer and the price is direct, which is not the case in healthcare.

“Health consumers don’t really care about prices unless they are paying out of pocket or are forced to make medical aid co-payments. This creates the opportunity for health professionals to inflate prices because there is little consumer pressure,” he said. “The government, therefore, needs to regulate doctors’ fees by creating a process that ensures fair price determination.”

How do doctors and dentists know what to charge patients?

There are no official guidelines other than what medical schemes are prepared to pay. Medical aids, even different plan options within the same scheme, all have different rates.

Mia Malan is the founder and editor-in-chief of Bhekisisa. She has worked in newsrooms in Johannesburg, Nairobi and Washington, DC, winning more than 30 awards for her radio, print and television work.