- More than a million public healthcare users in South Africa had started to use the HIV prevention pill by the end of May.

- Over half of people who have taken up the pill have done so in the past two years.

- We’ve broken down the latest health department data to make it easy to track where South Africa is with the roll-out of the pill — and we look at what we need to do to make the pill, a vaginal ring and two-monthly HIV prevention injection easier to access.

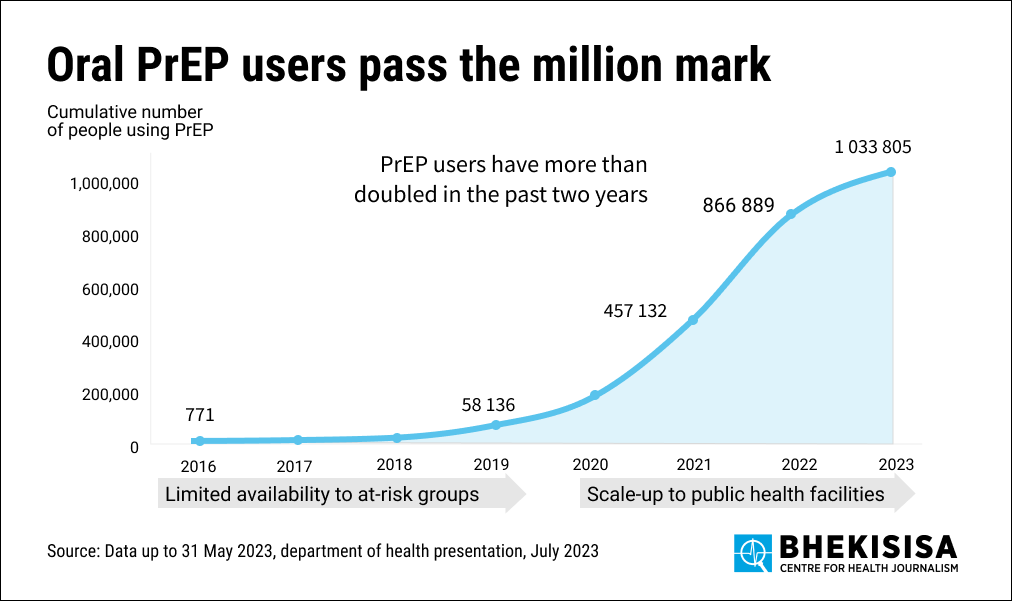

More than a million public healthcare users in South Africa — 1 033 805 — had started to use the HIV prevention pill by the end of May, with over half doing so in the past two years, health department data shows.

If taken daily, the pill, which consists of two antiretrovirals — emtricitabine and tenofovir — can lower someone’s chances of getting HIV through sex to almost zero. Antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) are the medicines that people with HIV take to prevent the virus from making copies of itself in their bodies, but in the case of HIV prevention (as opposed to HIV treatment), two ARVs instead of the standard three are used (our country’s entry-level treatment is a three-in-one tablet with tenofovir, lamivudine and dolutegravir).

Drugs taken to stop HIV from infecting someone are called PrEP, short for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Pills used for HIV prevention are known as oral PrEP because they’re taken through the mouth.

The health department introduced the pill in June 2016 to groups of people, such as sex workers and men who have sex with men, who have a higher chance than the general population to contract HIV. In 2020 it became available to anyone who wanted it, as long as the clinic they visited stocked it.

Three thousand seven hundred government clinics now stock oral PrEP, most of them in KwaZulu-Natal.

But the daily HIV prevention pill is no longer the only medication — or most efficacious — that someone can use to stop the virus from infecting them. A two-monthly antiretroviral injection known as CAB-LA (CAB-LA is short for long-acting cabotegravir; cabotegravir is an antiretroviral drug), was registered in South Africa in 2022, and studies have shown that it works even better than the pill and virtually wipes out a user’s chances of getting HIV.

CAB-LA, however, is considerably more expensive to make than the pill, and therefore also costs way more. It’s currently being sold in the United States for R54 000 a pop; a monthly supply of the HIV prevention pill in South Africa costs about R60.

For the past 18 months, donors such as the US government’s President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, Pepfar, and the Global Fund for Aids, TB and Malaria, have been negotiating with CAB-LA’s manufacturer, ViiV Healthcare, for a non-profit price. Although an official price hasn’t yet been announced, a cost of $240 (about R4 500) for a year’s supply (six injections) has been mentioned by various organisations, a price which Mitchell Warren of the New York-based advocacy organisation, Avac, says is likely accurate. He says as demand increases the price could very well drop to below $100, but that is still much more than the cost of the pill. Avac hosts a coalition that looks at how to make long-acting PrEP available as fast as possible.

Cheaper, generic versions of CAB-LA are likely to become available in about three to seven years, says Warren.

CAB-LA will be rolled out in implementation trials in South Africa from late this year or early 2024. Rather than testing how well a drug works, implementation studies look into potential roll-out problems and ways to get people to use them.

And that, says Linda-Gail Bekker, who is running an implementation trial at the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation at the University of Cape Town, is the most important thing to focus on right now: how to make PrEP appealing and easy to get. “Like the provision of fast food, where you have different ways, such as drive throughs, home deliveries, or pickup points, to choose from to order food, we need to offer people choices for how to get PrEP.”

And South Africa is well on its way to giving people those choices: in August, pharmacists, for instance, got permission to prescribe the HIV prevention pill, adding one more way (in addition to clinics) to access the pill.

In March 2002, another type of PrEP, in the form of a vaginal ring that is inserted monthly, was registered in South Africa. The ring, which releases an ARV, dapivirine, reduces a user’s chances of contracting HIV by about 30%. The ring is currently being rolled out in implementation trials in South Africa.

Warren says: “We need to offer people PrEP choices, and we need to do it in a way that is not stigmatising and doesn’t make it seem that health workers are focused on someone’s ‘risk’ of getting HIV and therefore stigmatising the pill, injection or ring. Rather, they should focus on talking to people about what they’d like to get out of their sexual lives, and how PrEP can help them to achieve that.”

We looked at health department data to see where the country is at with mass roll-out of the HIV prevention pill.

What has happened in the past two years?

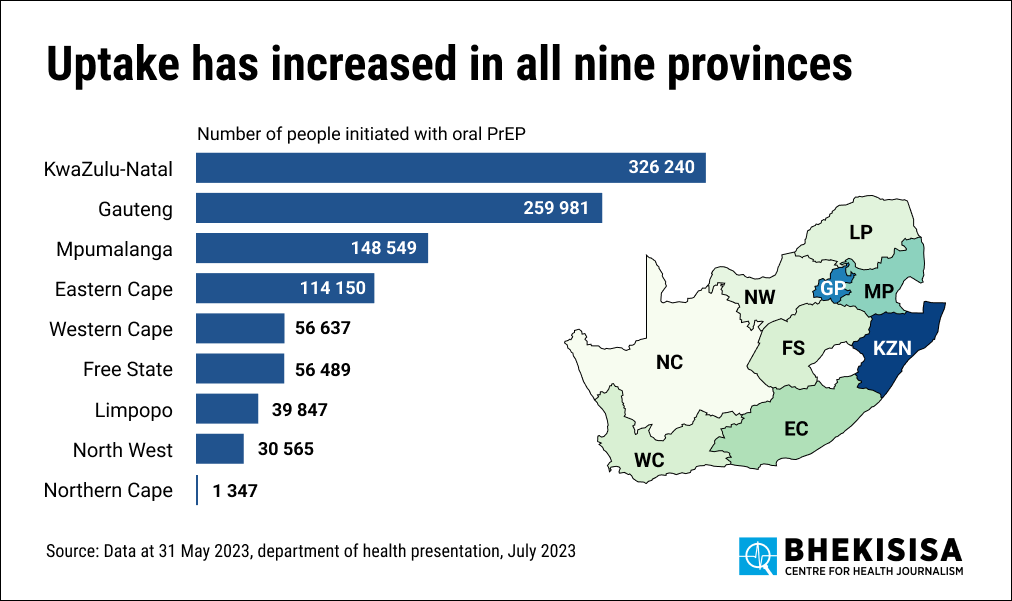

Over the past two years, many more people started to use the HIV prevention pill.

At the end of May, more than a million people (1 033 805) had begun using the daily pill — more than half (576 000) of them started using the medication in the past two years.

The HIV prevention pill was introduced in South Africa in June 2016 and it was initially only offered to groups of people (called key populations) who have a higher chance than the general population to contract HIV. Such groups include sex workers, men who have sex with men, teens and young African women, people who inject drugs and transgender people.

Four years later, in 2020, anyone who needed it could ask for the pill for free, if it was stocked by the government clinic they visited. The goal is to make the tablets available at all public primary healthcare clinics. When someone uses the government health system, a primary healthcare clinic is their first point of entry into the system (in the same way that people using private healthcare go to their GP when sick, public health users go to their primary healthcare clinic).

In 2020, however, COVID-19 hit South Africa, which slowed down the HIV prevention pill’s wider roll-out. But after the pandemic uptake improved.

Where are we now?

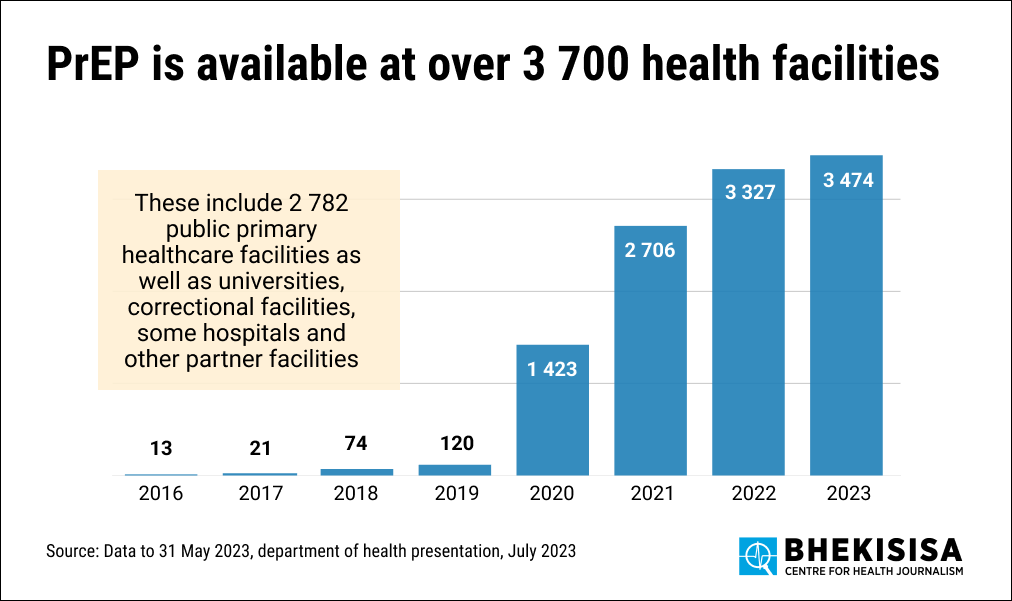

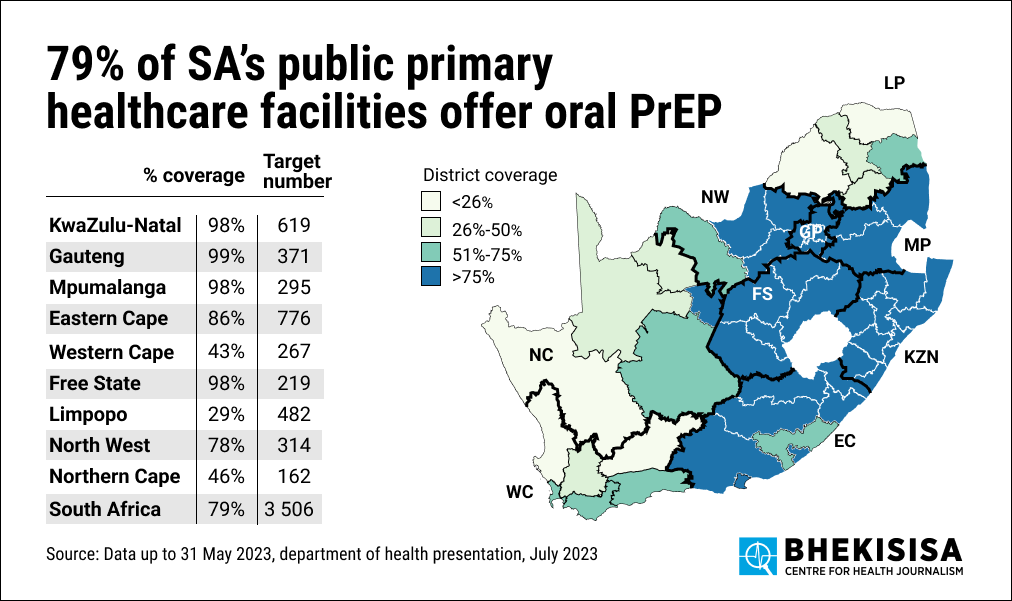

By the end of May 2023, the HIV prevention pill was available at 79% (2 782 out of 3 506) of primary healthcare clinics in South Africa. But it was also available for free at 960 other facilities not traditionally defined as primary healthcare facilities, such as clinics at universities, correctional facilities, hospitals and other partner facilities. The pill was therefore available for free at 3 747 facilities.

The health department’s goal for the 2023/24 financial year (1 March 2023 – 29 February 2024) is for the pill to be available at all of the country’s 3 506 government primary healthcare clinics.

By May 2023, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga and the Free State were close to this goal — at least 98% of primary healthcare clinics stocked the pill. But the Western Cape (43%), Limpopo (29%) and Northern Cape (46%) were still far behind.

In the 2022/2023 financial year (1 March 2022 – 28 February 2023), the health department’s goal was to get 461 372 people to start using the HIV prevention pill. They managed to get 421 236 people to take up the pill, so they reached 91% of the target.

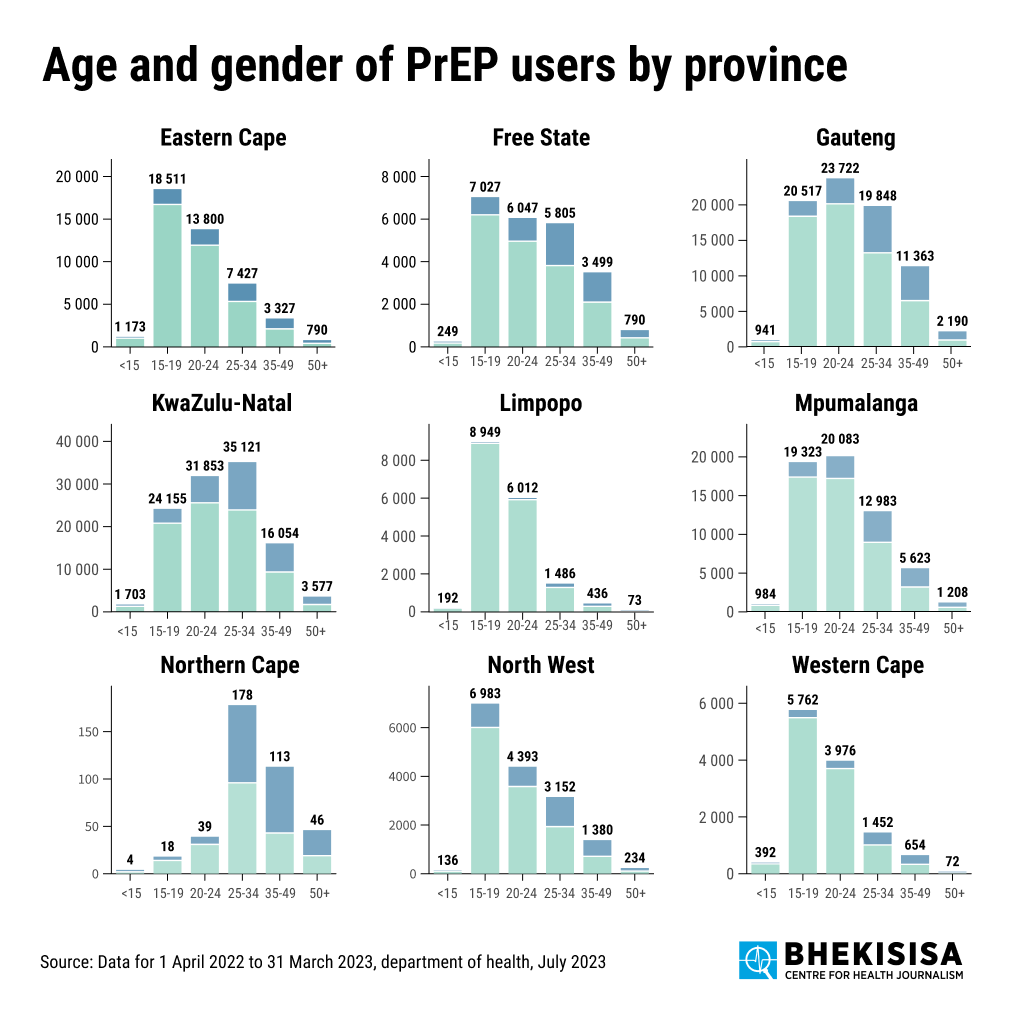

Most of the clinics which stock the pill are in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. KwaZulu-Natal is the province with the highest proportion of people with HIV in South Africa.

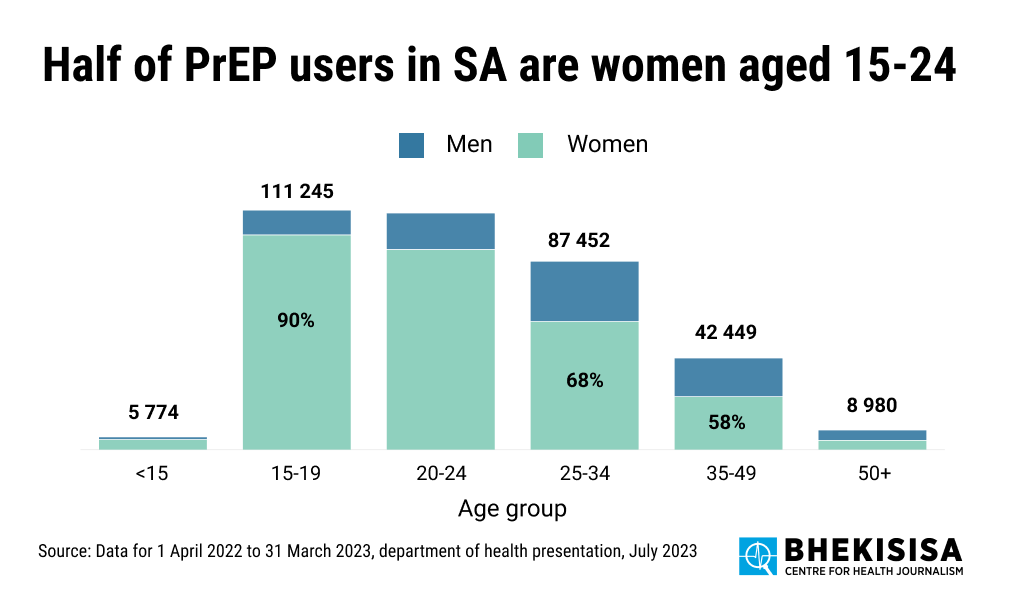

Women between the ages of 15 and 24 are the largest group of people in South Africa who have started to use the HIV prevention pill. They make up more than half (53%) of all the people who began using the pill in the 2022/23 financial year. This is also the group among whom new HIV infections are currently increasing the fastest in South Africa, indicating the need for them to be reached by PrEP.

In general, more women than men take up the pill.