State cancer patients have nowhere to turn, even if their cancer is treatable.

Alice Sibiya emerges from her bedroom, her jaw clenched. She carries three transparent plastic bags in her hands.

Sibiya moves purposely across her small living room in Inanda outside Durban. She lowers herself on to a couch and places one bag on her lap and the other two next to her.

Where Sibiya is seated, wearing a dress with blue and purple floral details, she is framed by gold curtains with clasps covered in artificial jewels. The subtropical sun is softened by a net curtain with faded embroidery.

Sibiya is in pain, but she’s trying to hide it.

For a moment, she freezes, then begins to unpack the loaded bags.

There are pills everywhere.

First, a small pill bottle labelled “Paracetamol” hits the table. Then a big box of tramadol, a mid-level painkiller, and three boxes marked “Pain Block”. A tub of Panados.

The first bag of pills is still more than half-full. The other two bags of medication haven’t even been opened.

On paper, 41-year-old Sibiya is a cervical cancer survivor. But almost two years after doctors at Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital deemed her cancer-free, she is still unable to work. “They [the doctors] told me I’m in remission. But I think maybe I’m not,” she says, putting pressure on her lower stomach with her palm.

“I’ve never been this sick before and I’m not getting any better. I thought God gave me another chance with the treatment, but I still can’t be happy.”

Sibiya’s bags don’t contain any cancer medication. All she has is painkillers – the type that are not nearly potent enough for her level of discomfort.

Outside, roosters crow loudly and the sun lights up a streak of the red linoleum floor near the doorway.

Sibiya looks away from the pile of pills opposite her. Her voice swells and fills the small living space.

“It’s always the same thing. No treatment,” she declares. She gasps tearfully. “I don’t even drink it anymore.”

Sibiya was one of about 2000 women diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2014, according to the latest South African Health Review data.

Cervical cancer, which is mostly caused by the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus, is the leading cause of cancer deaths for women in South Africa, 2012 estimates by the International Agency for Research on Cancer show.

Sibiya’s cancer was detected at a relatively early stage with a Pap smear, a test that collects cells from the cervix to detect cancerous growth.

She’s also HIV positive – this made her eight times more likely to get cervical cancer, a 2005 study in the National Cancer Institute journal has found.

But three years after her diagnosis, Sibiya is one of a growing number of patients affected by KwaZulu-Natal’s spiralling oncology crisis.

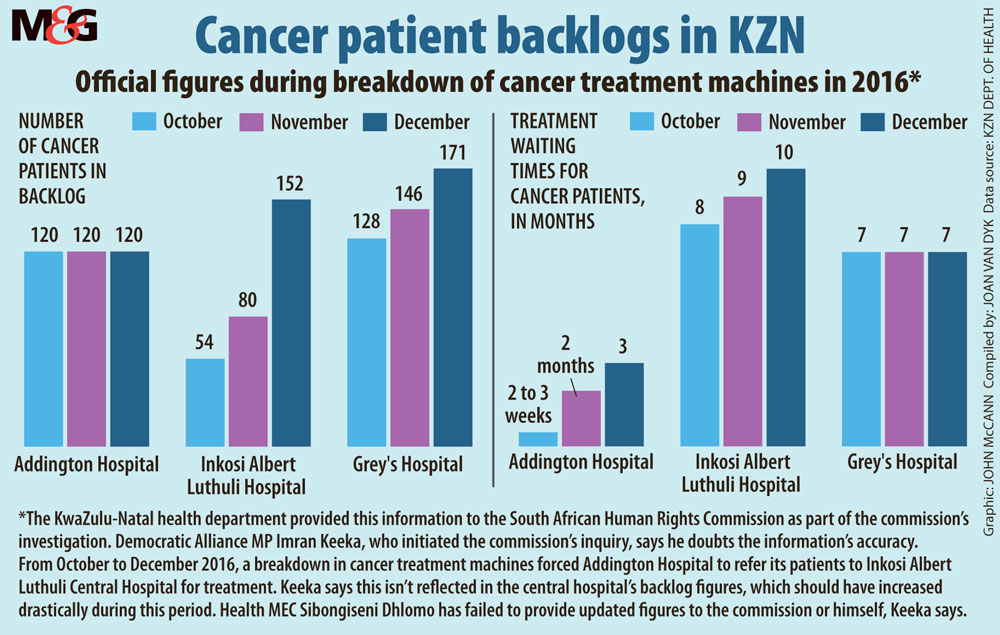

By 2015, a year after Sibiya found out she had cancer, a shortage of staff and broken treatment machines forced patients in KwaZulu-Natal to wait for five months to see a specialist, and a further eight months to start treatment, according to a report released by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) earlier this year.

In March 2015, Sibiya took a taxi to Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, referral letter in hand, to start chemo- and radiation therapy. But this was short-lived.

She speaks warmly of the oncologist who treated her then. But the physician left a few months later.

He’s not the only one to have done so.

In June, the last public-sector oncologist left Durban, leaving only two in the province – both working at Grey’s Hospital in Pietermaritzburg.

Almost immediately after Sibiya completed chemoand radiotherapy, she started noticing blood clots in her stool. “I was finally treated for that in 2016, but I’m still not sure what it was or what was happening. They just told me to come and get some painkillers.”

Sibiya says her 2015 appointment for this condition was rescheduled to October 2016 because machines at the hospital were broken.

Cancer treatment machines have been out of order periodically because of contractual disputes between the provincial department of health and its service providers. Findings in the SAHRC report indicate that, as a result, machines at Addington Hospital were broken between August 2014 and March 2016. During this time, all patients were transferred to Albert Luthuli Central Hospital for treatment on one of its three functioning machines.

“From my side, I only missed one appointment,” she explains. “That day … I was very sick. Everything was just dripping down my legs. I was just too sick to make it to hospital.” Sibiya continues, in a softer voice. “But when I got home it didn’t stop. The treatment I got in 2016 didn’t work. About a month ago I started going to the loo, you know … in the front … I was … getting faeces out of my vagina.”

When Sibiya reported this to the local clinic, the sister only gave her HIV medication and instructed her to return in three weeks if there was no change.

Three weeks later, in mid-August, her condition had worsened. Sibiya was sent from one facility to the next in search of specialist help. From the clinic, she was sent straight to Addington, and from Addington back to the regional Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Hospital.

“The doctors at Gandhi didn’t help me, so I had to come back the next day. But on Tuesday they didn’t examine me either. For three days, I was sent up and down to different hospitals with no help.” Each trip cost Sibiya about R50, close to 15% of her monthly income of R380.

“On that Thursday evening, I was admitted to Addington Hospital at 10pm. I was cold, and my cervix was painful. Luckily my sister brought me a blanket and warm pyjamas.”

She remembers the fitful seven hours that followed as she lay in a general ward and waited for doctors to examine her: “I would wake up every time the doctors did their rounds. When they finally came to me all they wanted to know was whether I was clean. Then they gave me pain pills.”

Sibiya slides an appointment card across the table with her pills, her eyes downcast. The date of her oncology appointment is scheduled for January 2018.

In August, the national department of health launched a two-week plan to save KwaZulu-Natal’s health systems after taking over some of the province’s procurement and human resources functions, says national department spokesperson Joe Maila. The department will now buy medical equipment for the province.

In March, KwaZulu-Natal reported a R1-billion overrun for 2017-2018.

But Russel Rensburg from the University of the Witwatersrand’s Rural Health Advocacy Project says these measures will only plug issues in the short term.

The province’s ailing health sector is a symptom of a national problem, he says: “The way we fund health needs to change. At the moment, provinces direct their own budgets to where they think the priorities are. In this case, cancer wasn’t a priority – and now people are dying.”

Rensburg says the cancer crisis could have been avoided if funds for health were controlled nationally. He explains: “This is why we need the National Health Insurance [NHI]. We need one pool of health resources so that we can cross-subsidise and prevent this from happening again.”

Under the scheme, the government will become the largest buyer of health services for all South Africans. The department of health released the final NHI white paper in June this year.

Rensburg also fears shambolic ANC politics in KwaZulu-Natal could draw key decision-makers’ attention away from the crisis in cancer care. The political leadership has been called into question after the Pietermartizburg high court last week ruled that the party’s 2015 provincial elective conference was illegal.

The Democratic Alliance’s Imran Keeka, MP in the provincial legislature for health and the main complainant in the SAHRC report, believes politics has already begun claiming lives. “MEC Sibongiseni Dhlomo has presided over the decay of this department for eight years. It’s his leadership that has brought the department to its knees,” he says. “The first step in curing the gangrene in KZN health is to amputate the problem. For as long as he remains at the helm people will continue to die.”

[WATCH] Cancer care crisis in KwaZulu-Natal

Back in Inanda, the inquisitive face of Sibiya’s 13 year-old son, Sihle, peers into the room from the window behind her. It’s a Monday morning, but Sihle has not been attending school. “When he went to school last Friday, he was wearing takkies because he doesn’t have school shoes. His teachers shouted at him for not having the proper uniform. I don’t think he will go back until he has the full uniform. I don’t know when I will be able to afford new shoes.”

When her treatment at Albert Luthuli ended in 2015, Sibiya was no longer eligible for a disability grant, which is reviewed every three months. In recent hospital visits, social workers have failed to help her reapply for the grant. Although she still receives a R380 child grant for Sihle, this is barely enough to cover the costs of a week’s food.

She continues: “I feel so guilty. He doesn’t understand that I just don’t have the money.” His school is encouraging the parents to pay for the children to go on a boat cruise for their grade 7 farewell.

“They’re saying we should pay because every child deserves to be happy, but the trip costs R430.”

Although Sihle has a room next to his mother’s, Sibiya is still often embarrassed by her condition. “When I’m not feeling well, Sihle will cuddle with me in my bed,” she says, her voice shaky with emotion.

When Sibiya gets up and moves towards the kitchen on the opposite side of the room, a half-healed scar is visible on her shin. “I don’t want him to see me when I have to change pads in the middle of the night. Sometimes, when I have diarrhoea, I can’t get outside fast enough because of the pain — I can’t even feel my private parts anymore.”The gash on her leg was caused when she was trying to get to the toilets outside in the dark.

Sibiya removes three navy containers labelled “mielie meal” from a white cupboard under the sink. Two of the containers are empty, the third contains about two cups of rice.

Behind her, the compartments of a wooden television shelving unit are filled with plastic containers and framed school photos of Sihle and his older brother Siyabonga. Two of the compartments feature her favourite decorative items – two white and pink dog figurines. “I love dogs so much. The best would be if I could get a job working with dogs,” she says.

A bright smile flashes across her face.

“Bobby, Bobby!” she calls in a singsong voice, summoning a big-eared, friendly dog from outside. “I love him – he keeps me company.”

Sibiya bends down and fondly scratches Bobby’s head.

“This morning I didn’t eat. But as you can see the maize meal buckets are empty. I cooked the last bit for Bobby. I wanted to make sure he had a meal.”

[Update: 21 September]: Bhekisisa has been informed that Sibiya received an appointment for the end of September after the nonprofit Cancer Alliance network intervened.

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.