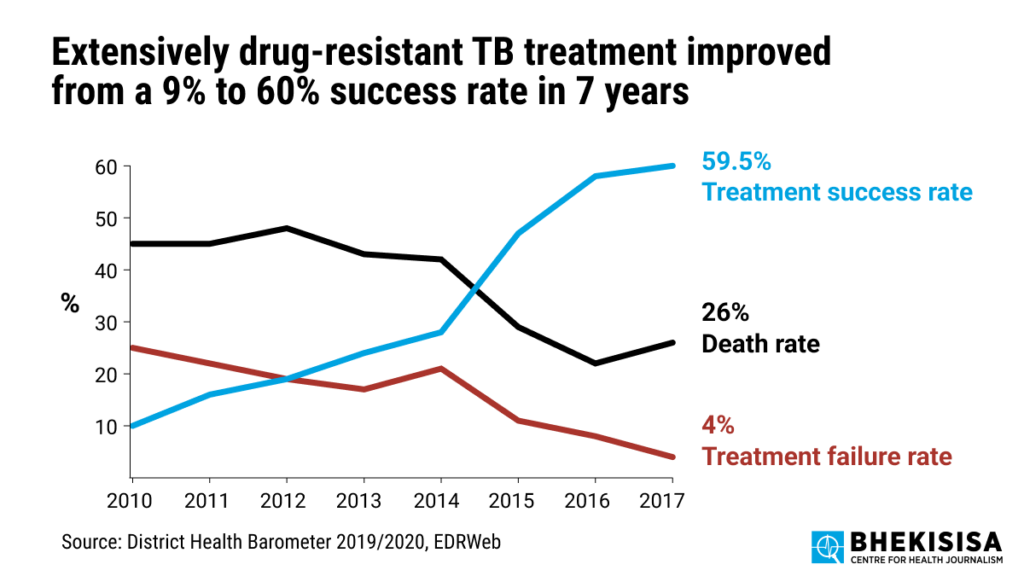

- Six out of ten people who were diagnosed with drug-resistant TB in South Africa, got treatment and beat the TB bug in 2017. This is six times more than in 2010, according to the District Health Barometer for 2019/2020.

- This is the most updated provincial data that’s publicly available, although fresh statistics could be coming soon since South Africa’s new TB action plan says it will collect data for every target in the document (many of which include boosting prevention and treatment for people with all kinds of TB).

- In partnership with Media Hack, we’ve compiled an interactive map to show how each province fared in 2017.

Six out of ten people who were diagnosed with drug-resistant TB in South Africa, got treatment and beat the TB bug in 2017. This is six times more than in 2010, according to the District Health Barometer for 2019/2020. The report is published by the Health Systems Trust each year.

But drug resistant TB, also known as XDR-TB, remains a huge problem — worldwide.

The World Health Organisation estimates that one in 14 TB patients won’t be able to be treated with the antibiotics that usually work.

XDR-TB is caused by TB bacteria that aren’t killed by either of the antibiotics normally used to treat TB (namely isoniazid and rifampin), nor any of the next-best type of drugs called fluoroquinolones, or another class of antibiotics, such as bedaquiline or linezolid. This means that people have little chance of beating TB and that many will die of a disease that is curable.

And because it’s difficult to identify these cases and track them, we don’t quite know how big our problem is.

Moreover, the health department’s statistics on how the country is doing at achieving its goals to curb TB, is far from complete, Yogan Pillay, who heads the Clinton Health Access Initiative’s South African team told Bhekisisa in February.

Current estimates from scientists’ survey say that about one in 20 of the country’s TB cases that can’t be treated with the first two choices of antibiotics (isoniazid and rifampin) is of the extreme kind. But the figure is based on an independent survey, rather than government-collected numbers.

We’ve put together this map to give a quick view of how South Africa is doing in dealing with XDR-TB.

Better statistics could be coming soon, though, since South Africa’s new TB action plan says it will collect data for every target in the document (many of which include boosting prevention and treatment for people with all kinds of TB). The new plan runs from 2023 to 2028.

In 2017, just six of South Africa’s 52 health districts managed to cure everyone who was diagnosed with XDR-TB. These districts were in the Free State, the Western Cape and Limpopo. But in eight districts, in Mpumalanga and the Eastern Cape, nobody finished a course of treatment successfully — which is one of the main ways how XDR-TB develops.

Why is XDR-TB hard to treat — and track?

If someone has XDR-TB, a treatment plan has to be set up especially for them, depending on which medicines they’ve used in the past, according to South Africa’s treatment guidelines.

That means health workers have to put together a detailed history of what medicines they used in the past, what worked and what didn’t.

They also have to send a series of samples to the National Health Laboratory Service, of which results can take a while to get back to clinics.

Apart from getting the data taking long and requiring a lot of sleuthing, patients also end up taking seven anti-TB drugs while they wait for the results about which of the remaining medicines could work, for nine to eleven months.

If the lab results show that these medicines won’t work for the patient, they will be switched to a longer course (11–20 months) with at least four medicines to which the germ is still responding as a last resort.

The best way to prevent XDR-TB is to stop people from falling ill with TB in the first place. Under South Africa’s new prevention guidelines (published in February) far more people who don’t have TB at the moment but may be at risk of getting infected, for example because they have a weak immune system or live with someone who has TB, will be able to get preventive treatment for free in South Africa’s public sector under a new “test and treat” policy.