- The health department plans to train professional nurses to prescribe pills for mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, according to the government’s new five-year (2023-2028) action plan for HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Mental health disorders make it easier for people to get infected with HIV and TB and harder to keep taking their medicine regularly.

- Currently, professional nurses cannot legally prescribe psychiatric medicines in South Africa, so Health Minister Joe Phaahla will have to change the country’s nursing laws before this plan can become a reality.

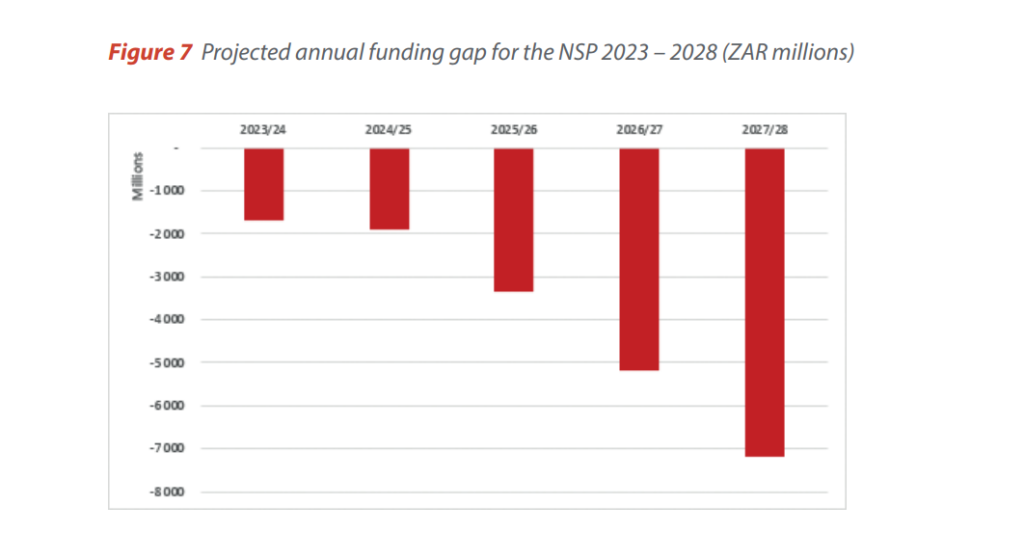

- But the HIV plan is short of more than R7.2-billion to achieve its goals by 2028. Meanwhile, international donors such as the US government’s Aids fund, Pepfar, have already indicated that they’d be decreasing their contributions in the near future.

Professional nurses may soon be trained to prescribe pills for mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety (under the supervision of a doctor), according to South Africa’s new five-year (2023-2028) action plan for HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

The South African National Aids Council (Sanac) launched the final plan in Rustenburg on World TB Day on Friday.

Health Minister Joe Phaahla will have to change the Nursing Act regulations to allow nurses to prescribe antidepressants, according to Andy Gray, a senior pharmacology lecturer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Currently, only general practitioners and psychiatrists can prescribe psychiatric medication in South Africa. Nurses can get trained to prescribe some medicines, for instance, antibiotics, but not mental health medication such as antidepressants because these medications are classified as schedules 5 and 6 medicines, which can only be prescribed by doctors, explains Gray.

About one in three people in South Africa will have depression, anxiety, or a substance use disorder at least once in their lives, according to the 2009 South African Stress and Health Survey. But three-quarters of people will never be treated, a 2009 South African Medical Journal study found.

Depression, anxiety, and substance abuse are much more common among people with HIV and TB than those not living with these illnesses, the plan says. Mental health conditions make it harder for people to keep taking their medication, and discrimination from health workers can result in people with mental health challenges not asking for the help they need.

Anxiety and depression also increase someone’s risk to contract HIV or TB (because anxious or depressed people often use coping mechanisms, for instance, substance abuse, that, in turn, make them more vulnerable to contracting HIV or TB).

That’s why it needs to be easier for people to get prescriptions for psychiatric medicine, the action plan says.

Professional nurses study for four years and receive a degree.

South Africa’s community health workers will also be trained to identify the signs of mental distress and substance abuse early on in the onset of such conditions.

But the new plan called the National Strategic Plan (NSP) for HIV, TB and STIs — which also aims to get more children vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV) which causes cervical cancer — has a funding gap.

For the first year of implementation, there is R1.7-million too little available to reach the plan’s goals — and such shortfalls increase for each year; by 2028, the last year of the plan, the cumulative deficit, as things stand now, is R7.2-billion.

What does the budget look like?

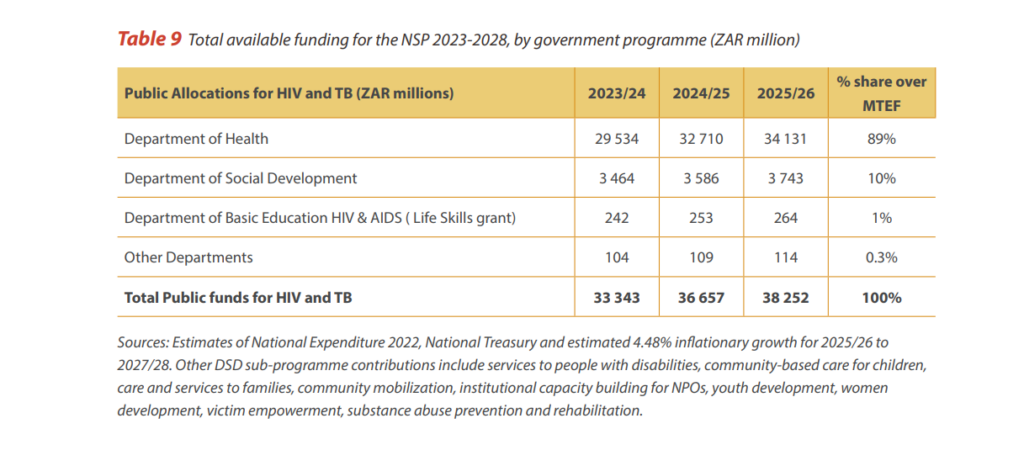

The government will fund the bulk (77%) of the NSP roll-out itself.

Another 20.5% of the money will come from international donors such as The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (6%), the US Agency for International Development and the US government’s Aids fund, the President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, PEPFAR, (14.5%).

South Africa’s private sector will contribute just 2.5% of the total costs of the NSP until 2028.

International donors have increased their contributions in the past couple of years to help South Africa reach its 95-95-95 targets, but as the country inches closer to controlling its HIV, TB, and STI epidemics, they will start to cut their funding, the plan says.

This is worrying, according to the NSP, because international partners invest a considerable amount into improving the country’s health system operations (for example, data collection). Donors also fund many community health worker programmes and projects that work with groups of people with high HIV, TB and STI infection rates, such as sex workers and transgender people.

What else is new in South Africa’s fifth NSP?

- The plan aims to get more people with HIV and TB tested and treated for diabetes, hypertension and cancer. This is to improve HIV-positive people’s life quality, especially once they’ve achieved viral suppression (this is when there is so little virus in their bodies that most lab tests can’t pick up the virus; this normally happens within six months after starting to take antiretroviral drugs, if the pills are taken correctly).

- The plan aims to start rolling out the HPV vaccine, which can prevent cervical cancer, to non-government schools. Currently, only girls in government schools qualify to get the jab for free. Research shows that cervical cancer increases someone’s chances to get infected with HIV.

- For the first time, the government will track HPV vaccinations in the same way it tracks HIV & TB treatment in the NSP. It aims to vaccinate 95% of girls aged 9 and older with the first anti-HPV vaccine by 2028. Eighty-five percent of nine-year old girls should have received their second dose by 2028 as well.

- The health department will push to decriminalise possession and use of drugs (in personal use cases). This means when the police find people in possession of drugs for personal use, they won’t be arrested. Studies show people who inject drugs have much higher HIV infection rates than those who don’t (often because they share needles). The report says that HIV and TB cases will decrease because when these drugs aren’t illegal there will be less stigma around drug use, which will make it easier for people to access health services. People are also at a higher risk of contracting TB if they’re imprisoned, or they might not have regular access to their HIV medicine.

- Sex work will be decriminalised. Studies show that when sex work is legal, sex workers are more likely to test for HIV and take up treatment if they test positive, which in turn, leads to lower HIV infection rates. The government will beef up screening, testing and treatment for viral hepatitis, an infection that causes liver inflammation and damage. Viral hepatitis progresses faster and causes more liver-related health problems among people with HIV than among those who do not have HIV.

- The health department plans to start 260 000 close contacts of TB patients on preventive treatment by 2028.

- The government aims to vaccinate 90% of newborns against hepatitis B by 2028.

Take a look back

Our journalists have reported on the draft version of the document, which was released late last year. Read their stories here:

- Find out why decriminalising sex work can protect sex workers (and everybody else) from gender-based violence.

- Or watch an episode of our television show, Health Beat, and meet some of the sex workers who didn’t survive to see their jobs become safer.

- Then, read about the problems with the way South Africa tracks sexually transmitted infections.

- Lastly, read about the medicine that can help people kick a drug dependence, and how the draft NSP planned to make it easier to access in South Africa.

Did you miss the health department’s launch event? Follow our live tweets below or read Deputy President Paul Mashatile’s speech.

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.