SA’s listeria epidemic is over. Take a look at the detectives who traced the epidemic’s source in this feature from our archives.

From its corner of the factory, the villain can see everything.

For years, it has reigned over its chrome kingdom of machinery. By now, its eyes are everywhere.

Watching. Waiting.

Moving only when others move. The bottom of a boot, a trolley wheel, a scummy drain are all perfect hideouts.

The other bugs were no match.

This villain had heard the whispers that the humans were sending their best to find him. But they still shuddered at the mention of its name: Listeria monocytogenes.

Medical scientist Mimmy Ngomane nervously closed the door behind her and locked it.

There was an important job to be done.

It was 5am, Saturday, 24 February.

Ngomane was called in to the centre for enteric diseases at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), in Edenvale east of Johannesburg, where she had been working for the past few years.

The centre, which studies diseases affecting the gut, was deserted. Ngomane knew its corridors well, but this time of the morning it was creepy.

“You start hearing doors open and close and wonder: Is somebody watching you?” she says.

She stole down the long corridor of the centre to one of its laboratories.

Ngomane was part of the team that had been working to track down the source of South Africa’s listeria outbreak – the biggest one the world has seen.

Scientists had been searching for the culprit for six months. But that morning was different.

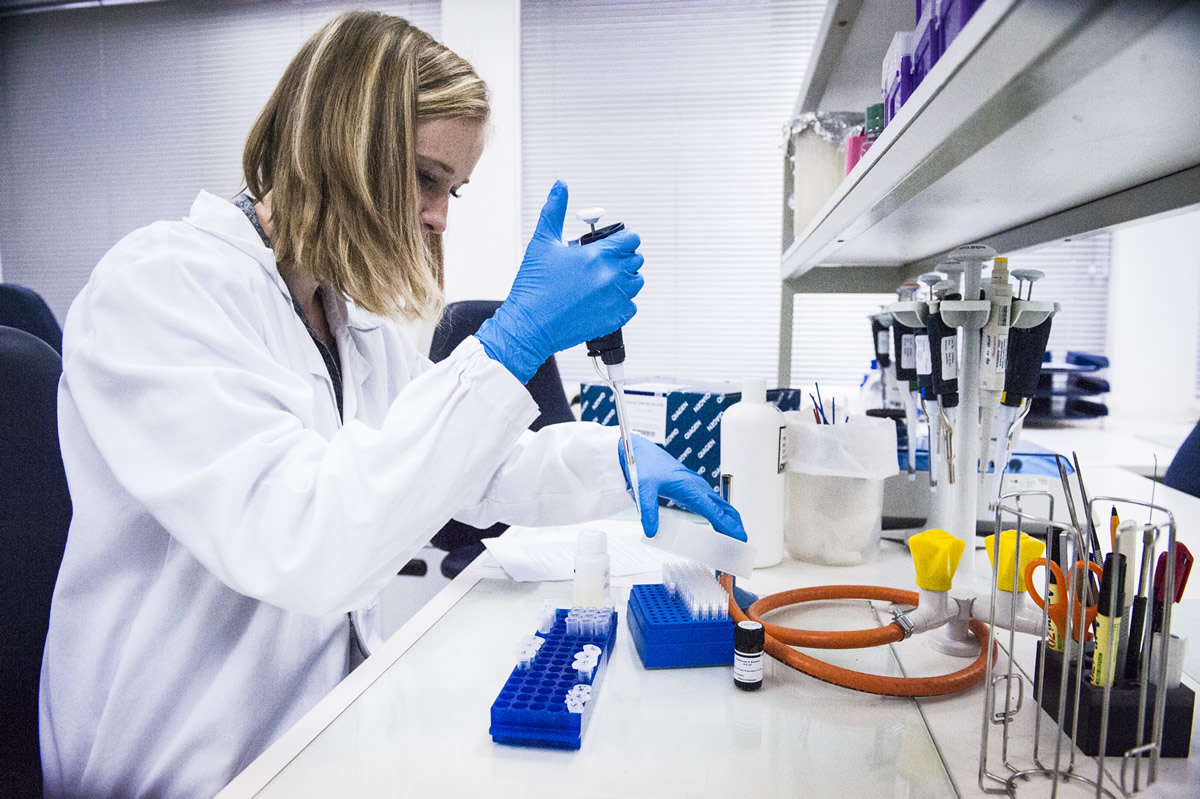

Ngomane had to prepare about 100 samples for DNA extraction. The samples were from Enterprise Foods’ cold meat factory in Polokwane.

Earlier that month, stool samples from nine children who were admitted to Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in January tested positive for listeria. The creche had served the children Enterprise polony.

The incident directed the scientists’ search to Polokwane.

Between January 2017 and March 2018, listeria had claimed almost 200 lives, according to NICD reports. Close to 1000 cases had been reported – about a quarter of those who were hospitalised had died.

Listeria can grow – and hide – almost anywhere. Dirty shoes, scummy drains, and cracked floors are “a huge blind spot in hygiene at the country’s food production plants”, says Lindiwe Mmatladi from the food safety organisation Partner for Hygiene and Technology. The bacterium also lives in machinery in food factories that had not been disinfected properly.

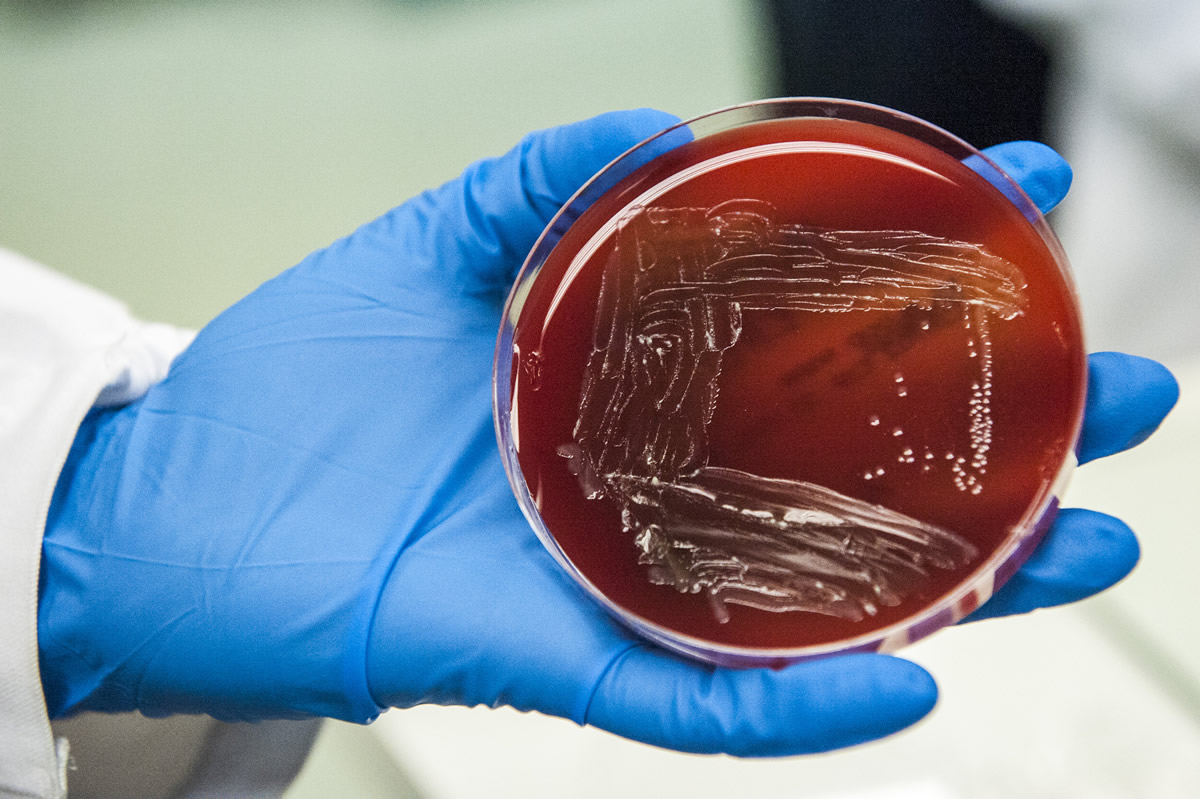

The extracted DNA in Ngomane’s lab would be used in a technique called gene sequencing. It would tell scientists whether the listeria germ in the samples matched that of the outbreak strain, known as ST6.

The batch of samples would take seven hours to to prepare.

Medical scientist Nomsa Tau points to a 1,5kg tub of Ricoffy in the centre’s kitchen. “There was no time to eat or drink,” she says. “I ran back here to gobble a muffin. But we were running on pure adrenaline.”

It was three o’clock in the morning on 3 February when researchers returned to the NICD with the samples from the Polokwane factory.

Among the team that had visited the plant, were representatives from the NICD, the department of agriculture, farming and fisheries, listeria and food safety experts from the World Health Organisation and environmental health practitioners.

The NICD’s Juno Thomas led the team.

When they arrived at the plant, two police vans were waiting in the parking lot – just in case.

Thomas explains: “We suspected we may run into trouble – so we arranged that the police meet us there. The environmental health practitioners had been refused entry twice before.”

The Enterprise staff there were anything but friendly. “Management was openly hostile towards me,” Thomas recalls. “I felt uncomfortable.”

Thomas’s views on the dangers of cold meat were well known. She had done many media interviews in which she warned South Africans that ready-to-eat meats, like polony, had been serial offenders in previous outbreaks of listeria.

At the factory, a staff member snarled at her: “People don’t know what they’re talking about. There’s absolutely no way it can be polony.”

The next day at the NICD, there was intense panic. Thomas had her hands in her hair.

She needed a certain solution to allow listeria in the samples collected from the Enterprise factory to grow, so that she could test whether they matched the ST6 strain.

But South Africa had run out of the nutrient-rich medium.

“For the first time ever, there was a national shortage of selective agar,” Thomas says. “Selective agar has vitamins, chemicals and antibiotics that kill off any other bacteria that could be in the sample — so only listeria will grow in the petri dish.”

Thomas and her team were forced to wait seven days for a new batch to be imported. And then it got stuck at customs. They were at risk of losing all the samples.

“If you don’t culture the sample quickly, other bacteria could overgrow the listeria – and we would have to start again,” she explains.

“We didn’t think we could get access to the factory again.”

A week later, the 104 glass vials with the extracted DNA from the factory samples rattled against one another as exhausted Tau walked up to the gene sequencing unit on the hill at the NICD.

In a room at the back of the unit, the NICD’s secret weapon had been doggedly decoding the genetic code of food and environmental samples.

The secret weapon was a gene sequencing machine named after the 007 secret agent, James Bond.

Tau was cautious, but hopeful. “You can’t really know if you’ve got anything until the sequencing is done,” she says.

Like its silver-screen namesake, this secret agent has state-of-the-art technology at its service. But it takes time. Five more days would pass before Thomas and her team would know if they had stopped this villain in its tracks.

[WATCH] You’ve binned the polony, but your kitchen isn’t safe yet.

Thomas got the call at half past 11 on Saturday night, March 3. She had been waiting all day. Her husband, daughter and cat were all asleep.

The NICD’s bioinformatics scientist Mushal Allam had finally finished analysing the genetic information. “We were expecting the results sooner, but Mushal was visiting his family in Sudan, and the internet was too slow to process the information quickly.

“There was nothing I could do. I was just watching the phone,” Thomas says.

More than 30% of the samples taken at Enterprise tested positive for Listeria monocytogenes. And a quarter of those samples contained the outbreak strain.

The case was closed.

The health minister was the first person Thomas called with the news. On Sunday just after midnight, Aaron Motsoaledi answered his phone, carefully listened to Thomas, and announced: “We have to inform the public. We’re holding a press conference later today.”

Listeria is the perfect villain, says US food safety legal expert Bill Marler. Marler arrived in South Africa last week to team up with legal firm Richard Spoor Inc in a class action suit against Tiger Brands, which owns Enterprise Foods.

“Listeria has been watching humans develop for years,” he quips. “It saw our fancy refrigeration systems and thought: ‘Ha! I’ve got you now.'”

Back at the NICD, the hum of the gene sequencing machine is getting louder.

Not far from the institute, people are lining up at grocery stories to return their polony. It’s about two weeks after the health minister’s Sunday press conference.

The customers don’t only have Enterprise cold meats in their plastic bags. Many have brought Rainbow Chicken polony too. The health department recalled Rainbow Chicken Limited’s cold meat products along with those of Enterprise Foods, as the NICD had found listeria in Rainbow’s food as well.

What the gene sequencing machine is doing, is testing whether the listeria in the Rainbow polonies is the killer strain, ST6.

And for those results, Juno Thomas is holding her breath. And the country too.

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.