- Anne von Gottberg and Cheryl Cohen are two of South Africa’s foremost scientists. We’ve got them and their colleagues to thank for the country’s world class surveillance of SARS-CoV-2.

- They’re also experts on how to bridge divides: Von Gottberg, who is German, and Cohen who is Jewish, got married in 2007.

- We visited them at their Parktown home and talked science, family and culture.

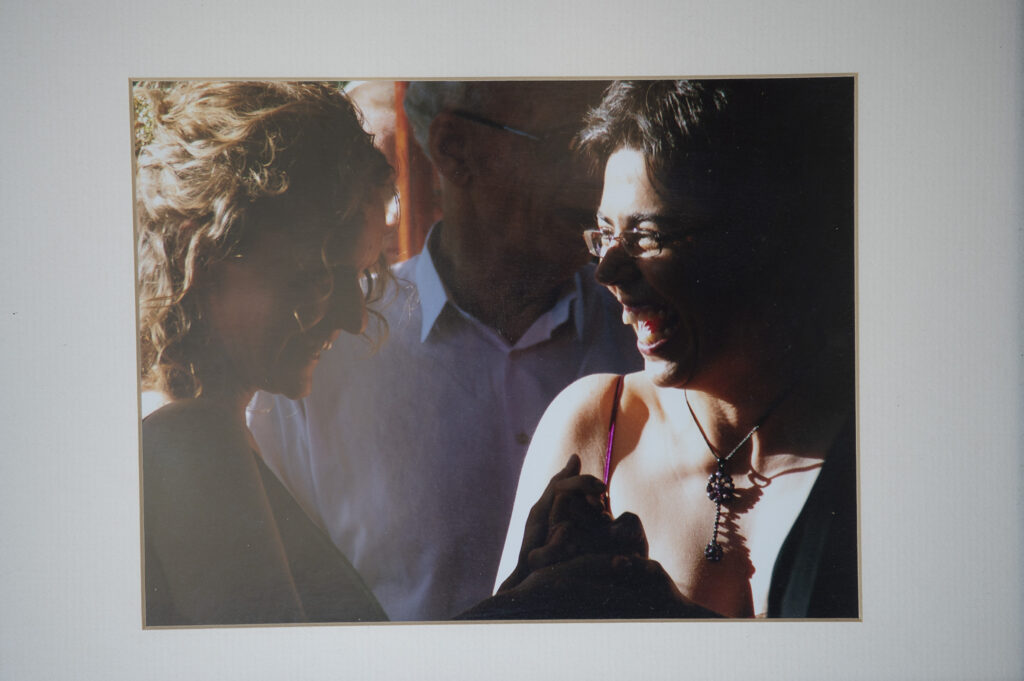

It was not by design that I met up with Anne von Gottberg and Cheryl Cohen on Heritage Day, but it certainly provided some laughs, given the polyglot nature of their family. Cohen is Jewish, von Gottberg’s heritage is German. With their three children, Sarah, Joshua and Daniel, they were preparing to celebrate Rosh Hashana (The Jewish New Year) in the coming week, while looking forward to Christmas. There was no Heritage Day braai smoking in the garden but von Gottberg made cups of rooibos, with milk.

“A very South African thing to do, putting milk in rooibos,” she observed.

I had spoken to both von Gottberg and Cohen earlier in the week, separately, over Zoom. We all agreed this was sensible — judicious, even — given the unusual degree to which their private and professional lives are integrated. They are married, they are both moms, as well as being medical doctors and scientists, and not only do they work together in the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), they work in the same unit of the NICD — the Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis.

Cheryl, who learnt how to say no

“We’re the pathogen specific experts,” says Cohen, who heads the Centre. Von Gottberg is in charge of the national reference laboratory for COVID-19 and other diseases, within the Centre.

South Africa has the two scientists and their teams to thank for the country’s world class surveillance of SARS-COV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), which was predicated on the surveillance and research infrastructure that both spent years helping to develop for influenza. Together with partners, their Centre corroborated that in South Africa, noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes place individuals at higher risk from COVID-19, and that people living with HIV, particularly those who are not on treatment, are also more likely to fall very ill with COVID-19 or die of the disease.

Finding time for conversations with these public health powerhouses was no easy thing. Von Gottberg was in Paris to attend a World Health Organisation meningitis meeting at Institut Pasteur. Shortly after her return, Cohen would be travelling to Belfast, to attend a conference on influenza and COVID-19.

“It’s getting busy again,” says Cohen, who explains that although the COVID-19 pandemic was “immense and emotional”, it had in many ways been very good for their family, and for her.

She says: “I haven’t had to travel out of the country for two-and-half years. In all of that time, I’ve put my children to sleep every night.”

The idyll may have ended, but Cohen says the pandemic period had left her better equipped to maintain balance in life.

“I read a very good article in the journal, Nature, about the power of saying no. Four researchers set themselves a target of one hundred no’s, and among their many findings is that saying no to certain things gives you space to do more of what you’re doing well. Don’t work with people who don’t accept your no!” she laughs.

Cohen’s ready smile and dark, pixie cut hair makes hers a friendly face, although a decisive nature is immediately apparent. I wondered if her boundary-setting techniques also worked on colleagues who happened to be spouses. Cohen laughs again.

“Anne and I do work closely together but with a different focus. I’ve always worked more on epidemiology — the data — and Anne is on the laboratory side,” says Cohen. She admits that working with a partner has its disadvantages, “but it also has advantages, and a big one is the fact that we trust and can backstop each other. When we travel, there’s no need to make long lists of ‘to do’s’. There’s reciprocity. It’s what enables us to have busy professional lives as well as a rich family life.”

In 2021, in her inaugural lecture at the University of the Witwatersrand where she is an epidemiology professor at the school of public health, Cohen compared the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, pointing out that the interventions were almost identical. She presented century-old pictures of courts being held outdoors and people wearing masks in public transport.

“The study of virology was still in its infancy and yet they had the concept of social distancing. What nobody explored was the impact of those interventions on the economy, which were perhaps masked by the first world war.”

She concludes: “We need a proper accounting now of COVID-19, so that, come the next pandemic, even if the virus is new, we will know more about the interventions.”

Anne, who likes being questioned

Upon her return from Paris, von Gottberg spoke to Bhekisisa via Zoom in an interval between two-hour-long power cuts.

After many “hi’s” and “can you hear me now’s”, von Gottberg describes the concerning impact South Africa’s loadshedding is having at the NICD: “We run tests on machines that require electricity, and which break down if they switch on and off too often. It has been a nightmare.”

Weighing more heavily on her mind than loadshedding, however, is the impact of COVID-19 on childhood vaccination services.

“Routine vaccine services bore the brunt of what happened in the last two-and-half years, and as a consequence we are seeing a rise in cases of vaccine-preventable diseases like pertussis [whooping cough] and to an extent measles. Polio is another vaccine-preventable disease that has appeared in southern Africa and will possibly soon appear in South Africa,” said von Gottberg, who is the chair of the national advisory group on immunisation, which advises the minister of health on vaccines.

The NICD has been calling for people to return to vaccination centres, and although routine immunisations were well accepted before the pandemic, especially infant vaccinations, von Gottberg is somewhat concerned that the hesitancy seen around SARS-COV-2 vaccinations will now “crossover to routine vaccination services”.

She says: “I am not frightened of the community questioning us and arguing with us — I think an engaged community is a good thing — but I think we need to anticipate this and be better at hearing concerns and responding to them.”

Tea, a drink with konfitüre and challah

So I knew a bit about von Gottberg and Cohen before meeting them at their home in Johannesburg’s northern suburbs on Heritage Day. Von Gottberg — petite, her fair hair cut off the collar — came to the gate and announced, “it’s just me and the kids at the moment. Cheryl, who puts everything on a very finely tuned timeline, is still at the shops buying goodies.”

A mezuzah at the front door would, soon enough, be joined by a decorative Christmas wreath.

“There’s a juxtaposition of cultural symbols in our house,” says Anne, passing a table on which several candles stand.

“I like to light candles for meals, even during the day, but have learnt not to light extra candles for Shabbat and definitely not to blow out the Shabbat candles after the Friday night meal!”

On the history shading behind their relationship and sewn into their identities — a non-Jewish German and a Jew, and both white South Africans who lived through apartheid — Anne says: “It’s heavy, but good for us and our children. We have a duty of great carefulness and responsibility for actions now and in the future.”

She introduces the twin boys — 9-year-olds Daniel and Joshua, a head’s height difference between them — and Sarah, 12, already taller than Anne.

“She wore my clothes for a while but they’re now too small,” says von Gottberg, to which her daughter responds with endearing umbrage: “They are not too small, they’re too short.”

Cohen arrives home and summons the kids to unpack the groceries.

“The fruit of our labours,” she jokes.

Cohen, incidentally, carried all three children, and “loved being pregnant”.

“I could eat for two and not get fat, and I was really filled with energy and wellbeing,” she laughs. Von Gottberg adds: “Among our many considerations was the fact that Cheryl was the younger woman with all the health benefits that come with that.”

Puzzles, scrabble and a humdinger of a wedding

“I mostly do puzzles with Joshua and Daniel,” Cohen explains. “Sarah used to. Anne doesn’t, or says she doesn’t, but actually, when it’s a really hard puzzle, she comes out of the closet and is excellent.”

Cohen — a scrabble fundi — says she and Anne had to give up playing scrabble together because their philosophies are too far apart.

“Anne thinks it’s better to make a nice word — something that’s clever and lovely — than a horrible but high scoring word. I can’t do that.”

It is at this point that the Rooibos tea is poured; we sit on the stoep, the kids coming and going. Anne says, “Cheryl often tells the story of how, when she was younger, she didn’t even believe that it was possible for her to marry and have children. But thanks to so many people who fought for our rights we had a humdinger of a wedding. For a moment Cheryl considered a second career as a wedding planner.”

They met as students, but there’s some debate about precise dates.

“Sometime in the late 90s at the University of Witwatersrand, where we both studied medicine,” Cohen explains.

Cohen’s mother was her inspiration for going into medicine. She grew up in Corlett Gardens in Johannesburg and recalls that her mother, a generalist with an interest in infectious diseases, attended interesting ward rounds at Sizwe Tropical Diseases Hospital, then called Rietfontein. Von Gottberg, by contrast, grew up in mining towns like Carletonville and Welkom — places her father had worked as a geologist — and came to Johannesburg for the first time as a medical student.

Both went on to specialise in microbiology, and for similar reasons.

“It was the height of the HIV epidemic, and due to a lack of access to antiretrovirals there was very little that clinicians could actually do for their patients. The public health system had its difficulties, too, and this made clinical medicine really gruelling and emotionally difficult, and so I chose to enter the laboratory,” says von Gottberg, who stayed very close to her specialisation.

Cohen also loved microbiology, and credits it with leading her into the deeply human enterprise of public health.

“Despite being lab-based, microbiology taught me the importance of the broader social context in determining, for example, how a disease spreads — contact patterns — and also how it can be successfully prevented,” says Cohen, who earned a master’s degree and a PhD in epidemiology, before moving into public health.

“The thing about being a clinician is that you are the product, and are therefore constrained by how many patients you can see in a day, whereas in public health, you get to take a broad view and design and implement strategies that have a hopefully beneficial impact for a large number of people, although on the flip side public health strategies can have unforeseen negative consequences, too,” she says, and cites the 2021 National Income Dynamics Study — Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), which found that the closure of schools during the COVID-19 led to more than half a million learners dropping out of school.

What went wrong on the caravan holiday?

Von Gottberg nods in agreement, son Daniel burrowing under her arm.

“Kids were disproportionately affected. Daniel and Josh learned to read during the pandemic period. If you happened to be six and lost two years of schooling … well, it’s not irretrievable but it requires a lot of energy and effort to make it up.”

Daniel pipes up that friends of his were on holiday when the first lockdown was implemented, “and they stayed by the sea!”

“A holiday that doesn’t end isn’t necessarily fun,” Cohen says.

“Oh boy, remember our caravan holiday?” asks Joshua, portentously. “Jungs wollt ihr euer Puzzle drinnen fertigmachen [You guys want to finish your puzzle indoors]?”, says von Gottberg, who speaks German to the children, but the boys aren’t interested.

What went wrong on the caravan holiday?” I goad.

“It started with Hogsback,” says Daniel, and between them the boys gave a breathless account of a road trip the family had recently done, which traversed multiple provinces and entangled the von Gottberg-Cohens and their hired caravan in many interesting situations, including a violent service delivery protest in the Eastern Cape, and a vehicular snafu on a perilous bridge in the Drakensberg.

The mothers exchange a look that held many meanings best known to parents, and others known only to themselves.

“We are an unstoppable force once we’re moving, the five of us,” Cohen says, and that is how I shall remember them.

Sean Christie is a freelance journalist and author.