- In June 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 crisis, Ebrahim Variava, head of internal medicine at the Tshepong Hospital in Klerksdorp, was suspended for criticising how the facility dealt with the health emergency.

- Variava is not scared to speak out against the ills of a broken public health sector, and growing up on the same street as Zackie Achmat, putting the plight of people first is in his blood.

- Meet the doctor whose passion for his patients is as fiery as his bright red scrubs — and who will work “outside the box” to ensure people get the right care.

In Klerksdorp spires stick up, not just the steeples of churches but the turrets of malls and the golden arches of McDonald’s, too. As you move southeast towards Jouberton, the built environment flattens out — simple houses and shacks to left and right. The tallest structure here is the three-storey main building of the Tshepong Hospital Complex, built of variegated Highveld brick, with a zinc roof and wide windows with white curtain backs in them.

For about 20 years now, Tshepong has punched above its weight. Once the last hospital choice of medical interns in South Africa, Tshepong is a popular option today, with no small thanks to the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) Medical School adding Tshepong as a satellite hospital in 2003.

It was one of the first public facilities to launch an HIV programme, which became one of the country’s busiest and most innovative, and its drug-resistant TB unit has participated in a roll-call of important global TB studies. Many contributed to the rise of Tshepong, but one man’s ongoing tenure straddles this relatively golden era. He is Ebrahim Variava, head of internal medicine.

I wait for him to finish his rounds in a large but worn and unadorned office on the second floor. I was interested to meet Variava, one of very few doctors working in the public health system who consistently speaks out about important issues — like stockouts of essential medicines or the effects of violent strikes on patient care.

For most, this would be career foreshortening — and indeed in June 2020, Variava was suspended without warning after internally criticising his hospital’s COVID-19 strategy, triggering a very public stand-off between the provincial health department and a group of his research collaborators and colleagues, who organised a petition. Variava beat the odds, and returned to work.

Judging from his tone while speaking on the phone as he enters his office, Variava’s zeal for frank talk is undiminished. Perhaps deliberately, he has a beret on his head — “à la the EFF” — and is dressed in fire-engine red scrubs, with the words “Prof V” embroidered over the breast pocket.

“Call me Brimey,” he says. “I’m quite pissed off.”

Touch and gos

At issue is the case of a patient he’s just seen.

“We have someone here who had an abnormal X-ray last year but it wasn’t appropriately followed up. He kept coming back, but we have these chaotic issues in hospitals where files get misplaced and new files keep getting made. So that’s what I’ve been doing today: trying to get all the files together to figure out what’s going on with this patient,” says Variava, speaking softly but with feeling.

As his investigations progressed, Variava realised he knew the patient. It’s worth reproducing his account without the interruption of quotidian verbs, for a sense of his humane eloquence.

“It’s someone who came here when I started in Tshepong in 2001. He had a cardiac problem and needed a double valve replacement. This chap used to drive a tambai [a local term for a community taxi] and the kind of service they provide is amazing: they will bring in disabled people from their homes to the hospital, which is something other public transport options cannot do.

“Well, his operation was very successful, and he used to hoot and wave whenever he saw me. But I haven’t seen him for some years — he’s had other doctors. Now it appears that he has this lung malignancy, which has simply been missed, and it seems to have progressed.

“I had to explain this to him and apologise and I must say, he took it amazingly well. He said, ‘No, it’s not your fault, it’s a problem with the files, we understand things like that.’ I don’t know that I’d be as kind. His case illuminates a series of issues we have in hospitals, like awful filing systems, and the lack of ability to deliver continuity of care.”

Variava has a name for public service doctors: he calls them “touch and gos”.

“They touch the life of a patient — and they disappear. It’s a problem in our public system. We get a lot of good doctors, but they rotate through the different departments and there’s no continuity of care. This is exactly what I’ve seen today,” says Variava, speaking with the kind of openness common to those with strong struggle bona fides.

A laatlammetjie who speaks out

Variava certainly has these, as do most of the members of his well-known family.

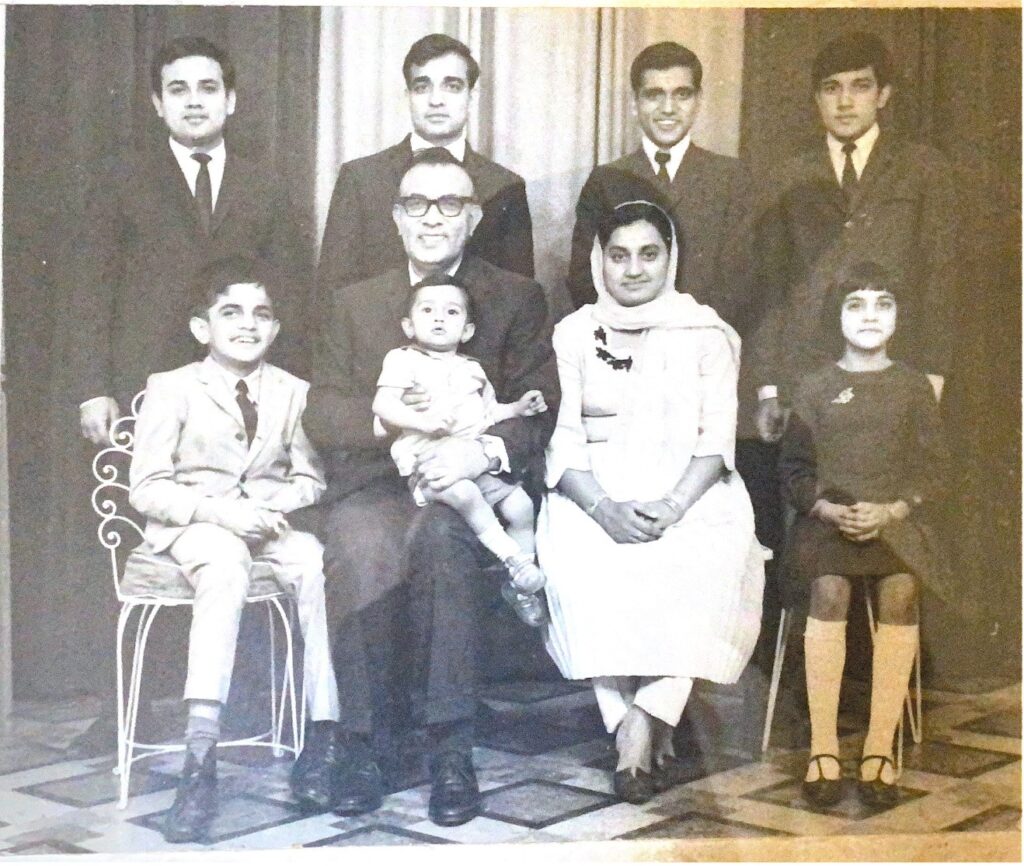

“I was born in Fietas in the centre of Johannesburg, the same place as Zackie Achmat, who grew up a few doors down,” says Variava, who was the “laatlammetjie among seven — six boys and one girl.

“My father was a clerk and my mother, who was quite a bit younger, was a self-taught cook and dressmaker. We were pretty hard up, everyone in the complex shared an outside toilet. We later moved to Lenasia, and although it was a forced removal it was, ironically, great for us to now have a house with a toilet and a bathroom,” Variava says.

He returns to the subject of his mother.

“She was an amazing woman. She stopped school in grade two, yet she was a linguist who could speak Afrikaans, Pedi, Urdu and all the Gujarati dialects. She used to sing, and she played a major role in the Muslim community. She saw most of us through school and university.”

Variava is 22 years younger than his oldest sibling, Yosuf “Joe” Veriava, who devoted his life to serving the public health system, and to defend medical ethics. In 1985, Yosuf Veriava famously led what became known as the “Steve Biko court case” against the South African Medical and Dental Council, which resulted in disciplinary action against the doctors who attended to the dying Biko and misrepresented the causes of his injuries.

“Your subeditor is going to ask you why his surname is spelled differently to mine,” says Variava, explaining that “it goes back to the day one of our uncles registered his birth. The authorities misspelled the name and my brother only realised his spelling was officially different towards matric, when he needed certain documents. He decided to keep it as is.”

Variava’s third oldest sibling, Haroun, went into exile in the United Kingdom in 1977, and was part of the Black Consciousness Movement there. His fourth brother, Sadecque, was involved in the founding of the South African Students Organisation and the Black People’s Convention, and was tried in the “Black Consciousness trial”.

“Our family life was often shattered by the appearance of the police, and I was reminded of these moments when I was suspended in 2020, because it similarly happened without warning. I was outside the ICU teaching young doctors about ventilation and the management of COVID-19, and people from human resources and labour relations came with this suspension letter and said I had to leave immediately — no finishing what I was doing, no going to the toilet without a chaperone,” Variava recalls.

An inability to tolerate bullying

If black consciousness was the ideological undertow in the Variava household, its intellectual subcurrents were many and varied.

“It was a house of readers and artists and debaters. My second oldest brother, Ishaack, used to play the guitar. My sister did her doctorate in philosophy at Cambridge University. I grew up with Sartre, Camus, Fanon, Foucault — all these guys — and listening to everything from Elvis to Hendrix. It never really stopped because I have three sons — Tariq, Aqil and Riyaz — and through them I’ve been exposed to newer stuff, like the protest lyrics of Public Enemy.

“And the movies! My brothers used to hire them, and four or five families would be in on the deal. We had this 16mm Bell & Howell projector, and we would watch something like The Godfather and then pass the reel on to the next house, and they’d pass it to the next, and so on.

“My brother Moosa, who we called Baboo, used to love movies, Westerns especially. He was mentally challenged but fairly functional and delightfully wicked — he loved watching people fall, and he liked to give them a little slap and then laugh, nothing aggressive. Growing up with him was amazing. He loved Springbok Radio and needed it on 24-7. When we moved to Lenz [Lenasia], we shared a room and I ended up listening to stories about squad cars and all the music from that little age, because he was there and I used to look after him and take him out quite a bit,” he says, clearing his throat. I can sense some transcendence taking place as the memory is provoked. We seem to be in another place, not in this hospital office with its smudged-window view of a desultory palm tree.

Variava matriculated from Nirvana Secondary school in 1983 and accepted a place in Wits medical school for the following year.

“I chose medicine because I wanted to become a psychiatrist — or rather an anti-psychiatrist,” Variava says.

“Thanks to the intellectual debate in the house and all of those books, I became aware of the South African psychiatrist David Cooper, who with guys like [the Scottish psychiatrist] RD Laing became prominent in the anti-psychiatry movement of the late 60s, basically arguing that a lot of mental illnesses were the result of dynamics in families and other social pressures. Instead of electro-shock treatment they started using hallucinogenic drugs as part of their therapies, and I was drawn to that, although once I got into medicine it changed,” says Variava, who was politically active from the outset.

In 1984, Variava’s brother Yosuf was working in Scotland. He switched on the television and saw scenes of protestors skirmishing with police in South Africa.

“The next thing, I see my brother on the screen, being beaten up by the security forces,” (Yosuf) Veriava recalls.

“South Africa was voting to elect coloured and Indian representatives to the Tricameral Parliament, and my brother was one of those going door to door telling people why they shouldn’t vote for something that aimed to entrench minority rule. On the day of the election there were protests and he was the sort of chap to go running to the frontline. This inability to tolerate any form of bullying is an attitude that has stuck with him, and even played a role in his professional commitments, because he stands up for his patients no matter the risk to himself,” Veriava says.

In 1987, Variava and other Black student activists made life difficult for the dean of the Wits medical school, Clive Rosendorff, by refusing to train in research hospitals designated whites-only, after being told they should ask female patients for their consent before examining them, while white doctors were not expected to do the same.

Variava later did his internship at Johannesburg’s Coronation Hospital (now Rahima Moosa) in 1992, where he met and began dating Dezlyn, who was studying ultrasonography.

“It was the time of the Third Force, and people who had political vendettas were throwing people off trains. The victims used to come into our hospital with the most horrendous injuries. We learned how to manage, so in spite of the horrors it made us better clinicians, a strange contradiction,” Variava says.

Working outside the box

In 1993, the couple decided to quit the city for the deeply rural Shongwe, near the borders of South Africa, Swaziland (eSwatini) and Mozambique. Variava had taken a job as a medical officer, overseeing 16 clinics.

“It was an amazing time. I would just jump in my car and drive through beautiful scenery with the Lebombo Mountains nearby, as far as Mbuzini, where Samora Machel’s plane came down and where they used to deliver babies by the light of kerosene lamps,” he recalls. Variava shared a house with a team from Médecins Sans Frontières here, who were attending to refugees from the civil war in Mozambique.

“It was from their guys that I learned about care groups. Their doctors had noticed that many kids were suffering from kwashiorkor [protein deficiency]. Even though they would address the issue, the patients would come back in again with the same problem. So they created a nutritional rehabilitation unit at the hospital, and they started teaching the children’s caregivers how to grow beans and other protein sources, and the kids started to do well. And they took these mothers to the local clinics to provide training for other mothers, who went back to their villages to teach the mothers there how to provide appropriate nutrition. There was a sudden drop in case numbers, and I became interested in how you can use people to improve things for the community.”

To be closer to Dezlyn’s family, the couple moved to KwaZulu-Natal in 1994, and were married the same year. Variava fondly recalls watching the sun rise from a bench on the South Beach promenade after 24-hour shifts at the Addington Hospital in Durban.

For his registrar training they returned to the Highveld, to work in central Johannesburg’s newly desegregated hospitals, and after specialising in internal medicine Variava joined Leratong Hospital in Krugersdorp. He was on call every weekend, and burnt out.

“It was at that point that I sold my soul,” Variava says, poker faced.

“A friend of mine who worked for Anglo American came to me — he knew my beliefs — and said, ‘Anglo is not a bad health service, and you can make a change.’

“I had bought a house, we had just had a kid and the salary was double what I’d been getting, so I took the job, which was in Welkom. I learned a fortune: about mining, about lung disease and silicosis, about TB. But there were a couple of things I didn’t like,” says Variava, who used to get letters from the mine managers asking him to either book his patients off permanently or clear them for work.

“I used to write back and say that I’m not a mechanic employed to fix tools to be taken back underground. I’m here to help my patients if I can and I’m not going to rush,” says Variava, who was also disturbed by the company’s approach to the issue of cryptococcal meningitis, a fungus of the brain that is, after tuberculosis, one of the top killers of people with advanced HIV.

“After diagnosing it we were expected to fill in a terminal leave form and the person would be cut from the workforce and sent home without treatment, because they felt that the drug for treating it — fluconazole — was unaffordable. The manufacturer, Pfizer, had donated a quantity of this drug to the state, and so instead of filling out the terminal leave form, I would send my patients to the public hospital for treatment, to a friend who was working there.”

When management figured this out they called me to a table and drew me a box and said, ‘We need you to work within this box.’ I said, ‘No, you guys may pay me, but I work for the patient. If the solution doesn’t lie within your box, I’m going to push it out.’ Well, they pushed me to resign and I did, because I was so emotionally stuffed from having to watch the awful natural life cycle of cryptococcal meningitis again and again, without being able to do anything about it.”

Patients are the priority

On the day he resigned, Variava received a call from a man who used to be their family physician, Hamid Wadee.

“He had moved from Lenasia to Klerksdorp and was the superintendent of Tshepong Hospital at the time. He asked me if I wanted a job as a senior specialist. In the end I was offered the position of principal specialist, and I took it.”

The North West province MEC for health was Molefo Sefularo, and he stuck his neck out allowing Variava to set up an HIV clinic at a time when “the national minister was up to crap, espousing garlic as a cure for Aids”.

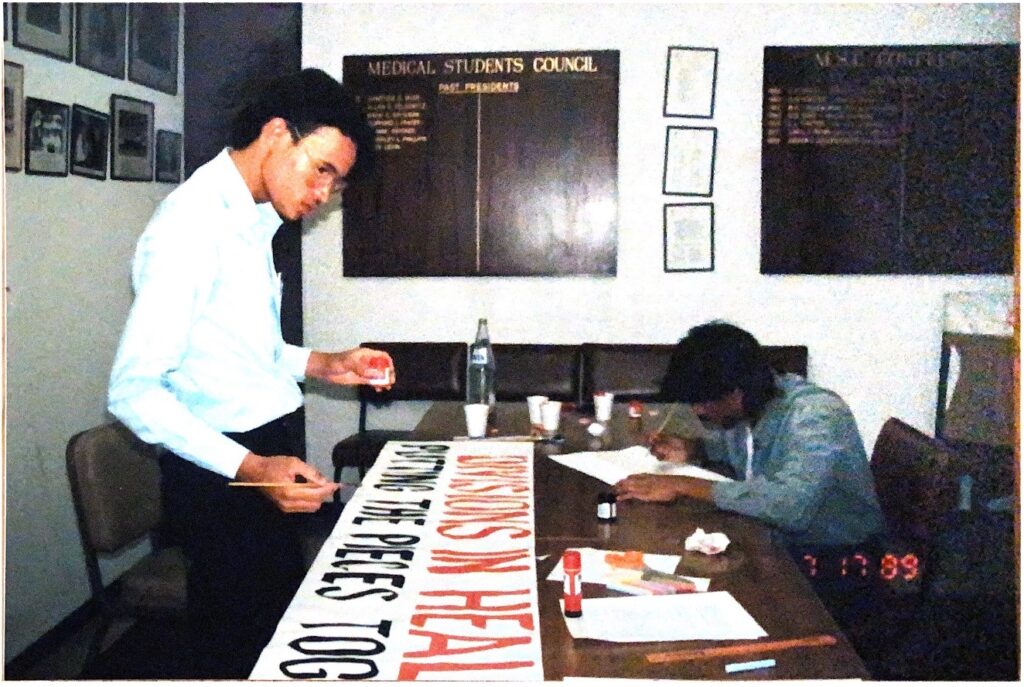

“He said, ‘Go ahead, just don’t make a noise’, and that’s how we started,” recalls Variava, who established one of the most innovative HIV programmes in the country, working with Francois Venter and the Reproductive Health & HIV Research Unit (at Wits) to train clinic nurses to start patients on antiretrovirals.

A longtime collaborator of Variava’s, Neil Martinson, says he was “impressed by Brimey’s can-do attitude” when he first met him in 2007.

“He was enthusiastically diagnosing and treating people with HIV, and had these innovative research ideas, based on clinical experience in wards treating critically ill patients. This prompted us [the Wits Perinatal HIV Research Unit] to do our first collaborative study at Tshepong,” says Martinson.

One of those ideas was a strategy for referring HIV patients to general practitioners (GPs) in private practice for their ongoing treatment and care, and paying them to do this.

“If you think about it, it was similar to some of what the government wants to do with the NHI [National Health Insurance]. We pitched the idea to the US-based BroadReach Group and they liked it and funded it. The programme ran for about eight years with 20 participating GPs and over 5 000 patients. We had plenty of critics, but then the results came in — and they were unheard of at the time: retention in care at about 97%, and 93% of patients in the cohort had undetectable viral loads,” says Variava.

The two Public Service Innovation Awards certificates hanging on the office walls now make sense.

The health department declined to take over the programme, after initially promising to do so, though.

“There was a change of leadership. Priorities shifted,” he says, and after a pause: “This place isn’t what it once was — the brass things no longer shine the way they used to. We have three CT [computerised tomography] scan machines, but often there’s no toilet paper or too few blankets. Everything is going down. In my view, the early cadres were a bit more committed, because they were fresh from the struggle. But lately it’s just vulgar self-interest in every direction,” he says, and it is difficult to tell whether Variava is jaded, or, like the archangel played by John Travolta in the movie Michael, he’s simply incapable of passing up a fight.

“I am tired,” he admits.

“I draw strength from the young doctors that come through — I don’t want them to pick up the same attitudes that we have, like the avoidance of real work, and trying to find real solutions to patients’ problems. The young doctors keep you alive, even if they do watch movies on their phones, which is just so anathema to a relic like me.”

Aqeela Moosa was one of those doctors. She first encountered Variava while doing her community service year in Mafeking (today Mahikeng) and later did some of her specialist training at Tshepong.

“He has a fiery temperament, but it’s righteous anger,” she says.

“From day one, you know that if the patient isn’t your absolute priority, you’re not going to survive. And it isn’t just lip service with Brimey; he actually shows you how to put the patient first. If there are medicine stockouts, he will make a hundred calls to sort the issue out, and if it’s impossible to get a particular drug he’s very good at coming up with alternatives. I remember when we had no medicine to treat hepatitis C patients, he managed to secure leftover trial drugs from one of the universities.”

Variava was anything but aloof in his dealings with younger doctors, though. “If you invited him to a party, he would come. We had a farewell thing once and because there isn’t much nightlife in Klerksdorp, we went to an arcade and Brimey got stuck into some motorbike racing game!” Moosa recalls.

Democratising healthcare

Before leaving Variava’s office, I notice a device on the table.

“It’s a portable ultrasound device I bought from the United States after seeing it on the telly. It has transformed the way I practise medicine,” he says, and demonstrates, by percussing my chest, the difference between the old way of checking for pneumonia, and what his sonography machine can do with far greater precision.

“They’re made by a company called Butterfly IQ, which claims to be on a mission to democratise healthcare. I believe in this. I mean, doctors have been stuck with the stethoscope since [around the time of] the French Revolution. This [thing] gives us eyes, it gives us vision,” he notes.

It occurs to me that the Brimey Variavas of the world do something similar: identifying symptoms of systemic sickness that others have missed — or prefer not to find — and revealing them to the rest of us for what they are.

Sean Christie is a freelance journalist and author.