- In 1969, Esther Mwaikambo became Tanzania’s first female doctor. Today, she is arguably also the country’s most famous.

- In her career of almost 50 years as a paediatrician, she’s seen infant deaths in the country drop by more than five times.

- At a conference held just north of Tshwane in September, where healthcare elders from across Africa shared lessons from their careers for a better future on the continent, her contribution has been generous.

- Mwaikambo tells Sean Christie how public healthcare in Africa has changed — and what she wishes for the future.

Professor Esther Mwaikambo looks out at the Highveld rain dripping from the monkey thorn trees outside the foyer of the Intundla Game Lodge, just north of Tshwane. She has just participated in a breakaway session on maternal and child healthcare at the Public Good, Planning and Internationalism in African Health conference at Roodeplaat. As a paediatrician of almost 50 years’ experience, her contribution has been generous.

But so is her history. She became Tanzania’s first female doctor in 1969. Today, she is arguably also the country’s most famous.

There’s no shortage of legendary clinicians at the meeting, which has brought together healthcare elders from across the continent in September to talk about the beginnings of public healthcare in African countries after independence, how it’s changed and where it’s going.

But Mwaikambo is both the gathering’s star and its darling.

I’ve been tracking her for days, as have many academics, and as I approach now she shoots a quick glance at the heavens, sighs good naturedly, and says, “Ok, I’m trapped by this downpour, I suppose you can ask your questions.”

Out of Africa

Mwaikambo was born on the slopes of Kilimanjaro in the village of Mwika Moshi during the second world war.

“My family had a farm in Africa,” she says, “but it was nothing like the one in the famous book [Out of Africa by Karen Blixen]. Ours was 1.5 acres, a standard plot.”

She, her sisters and her mother worked the land, as their tribe, the Chagga, expected them to.

“I hated cleaning out the animal house and then taking the dung to the banana farm as fertiliser,” she recalls.

Mwaikambo’s mother, Eliaiho Ngoiya Lyimo, and father, Daniel Lengaki, had nine children, of whom Mwaikambo was the fifth.

“Eleven under one roof, and we had nothing at all. But we were happy.”

It was common practice at the time for parents of multiple children to send some of their brood to work in the homes of friends and relatives, and at the age of five this became Mwaikambo’s lot. She was sent to live in her godfather’s house, where she took care of the home, tended the animals — and felt very homesick. Eventually, when her elder sister, Dora, was sent to school, Mwaikambo demanded that she be allowed to attend too, and her father agreed.

“He was a traditional man but fully supported his daughters’ education. I will forever be thankful for that.”

Mwaikambo is petite, her face extraordinarily youthful for her years. Her lapelless blazer and mauve polo neck suggesting time spent in educational environs. The rain is falling with such force now that atomised particles cling to her micro-braids, which she has tied into a ponytail.

“After passing regional examinations I was selected to go to Ashira girls school, a boarding school near to my home. On weekends, I could now return to my own family, which I loved,” says Mwaikambo.

But her happiness was short-lived.

“My mother’s left eye started causing problems. It looked bad, filled with pus and discharge. She’d dress it and try to carry on, but it worsened, and when I was 10 years old she died. It shattered our lives, and with so many young children to care for, my father could see no way ahead,” Mwaikambo recalls, adding that fellow villagers believed that her mother had been bewitched, “which made everything worse”.

In her grief, Mwaikambo decided it would be her life’s mission to find out exactly what had killed her mother.

“I wanted to bring the invisible into the open and give it a name. I knew that there had to be an explanation.”

At the age of 14, Mwaikambo was selected to go to the “highly reputable” Tabora girls secondary school, 800 kilometres away in north-western Tanzania.

A life story

“Hang on,” she says, fishing in her bag and producing a slender book, with a picture of her face on the cover, and above it a title, The Tanzanian Woman of Many Firsts.

“It’s the story of my life, my last copy,” she says, thumbing her way towards the sought-for page, and then circling a paragraph with a fingertip.

At night, I read aloud, we’d hide kerosene lamps under our blankets and read our textbooks until the small hours of the morning. If the matron had popped her head into the dormitories, she’d have seen rows of little lanterns blurred under duvet covers and heard the sounds of scribbling pens and pencils and the turning of pages.

“Nice.”

Mwaikambo smiles broadly.

“Well, we knew that we were there to pass our examinations, not to find boyfriends, and that this required a huge amount of discipline and dedication.”

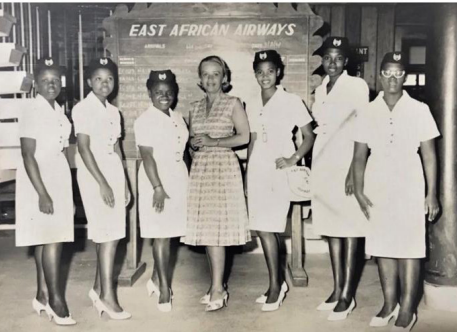

After Tabora, Mwaikambo enrolled at Dar es Salaam Technical College for a one-year secretarial course, and after qualifying was posted to Mbeya Provincial office, where she worked as the personal secretary of the provincial medical officer. Under-stimulated, Mwaikambo resigned after a year and took a job as an air hostess, becoming one of the continent’s first African flight attendants, only to resign from this job after a few months.

“I’ve always wondered what was pushing me. I just know that there was always something — some sense — telling me ‘this is not where you settle’.”

Mwaikambo grew up in Tanganyika, under British rule, but by 1953 when she was 10, Julius Nyerere, as president of the Tanganyika African Association, had begun campaigning for independence, calling for Uhuru na Umoja (“Freedom and Unity”), a dream he achieved in 1961 when a republic was declared, with Nyerere as its leader. Tanganyika was renamed Tanzania.

“It was a shift in identity, and suddenly there were all these opportunities to go and study abroad,” Mwaikambo recalls. The idea appealed to her, and since science and engineering courses were not offered to women, she opted for journalism, and was accepted onto a course in Moscow.

“Effectively, I was desperate to get out of Tanzania and see the world.”

Brown bread and black tea

Mwaikambo was shocked by the living conditions in Moscow, where she and her fellow expatriate students “lived on brown bread and black tea”.

“Many of us Tanzanians went there but just eight ended up qualifying — all the others went home. Our teachers were excellent, but it was impossible to carve out an individual personality in Russia, where people had to toe the party line. The Russians were generally hesitant to make friends with us, and there was a limit as to the contact we could have with them.”

Mwaikambo was struck, however, by the fact that most of the doctors she encountered were women.

“I was told it was due to the war, to the shortage of male applicants. I had no idea beforehand that this was possible, and once I found out I knew immediately that I wanted to do a medical degree. “

To become eligible, Mwaikambo had to go back to school, and she did, this time in Russia, where she studied physics, chemistry, biology and mathematics.

“Nothing could have put me off,” she says.

In 1965, Mwaikambo was admitted for a medical degree. When she returned to Tanzania at the end of 1969, she could rightly claim to be the first woman in the history of Tanzania to become a medical doctor. She would be celebrated for this achievement, but for Mwaikambo a more poignant thing took place mid degree: she finally found out what had killed her mother.

“It was an eye cancer called retinoblastoma, a tumour which starts in the retina [at the back of the eye] and grows into the eye and nearby structure. An early diagnosis might have saved her life, but by the end there was nothing anyone could have done for her,” she says.

Mwaikambo’s entry into Tanzania’s public health system was illuminating.

“Thanks to the legacy of colonial thinking, which was little concerned with the health of locals, there was still virtually no structured healthcare service and a lot of people were falling sick and dying from preventable diseases. I witnessed a great deal of misery in Russia but not a lot of death, and so my return to Tanzania was a trial by fire — I was particularly struck and affected by the number of children dying in front of me,” she says.

As a registrar at the former Dar es Salaam Medical School (today the Muhimbili University college of health and allied sciences), Mwaikambo’s first posting was in the obstetrics and gynaecology department, and her next posting, which was in the paediatrics department, set the course of her professional life.

“I immediately knew that this was where I wanted to be, for the simple reason that children were dying, up to six a day.”

In Russia, with love

Mwaikambo embarked on the process of specialising in 1974, and in 1977 she became the first female Tanzanian paediatrician.

“Some of the credit for this has to go to my husband, Gibbons James, who I met while at high school but only came to know in Russia, where he was enrolled in an economics degree. We became friends and were married in 1967 in a small ceremony,” Mwaikambo says, adding that she was somewhat shocked to learn that James was the son of a chief from a village near Mbeya in the Southern Highlands, where he was “treated like a demi-god”.

“Fortunately, he was not traditional in his attitudes towards the villagers, nor me.”

The couple would adopt five children — Elizabeth, Ndeonika, James, Gwamaka and Nick. In her memoir, Mwaikambo writes:

It is far more common in Africa to take on non-biological children: quite often other families will simply bring them to you, especially if they know you don’t have a child of your own. In the end I had five brought to me, often at the age of around two years old, but sometimes a little older. There’s nothing so rewarding as watching the children you raised take on the world independently. And it brings a new dimension to a marriage, too, I think: suddenly the pair of you are responsible for things outside yourselves and your relationship. I love being a mother, and I love too that I’ve been able to balance my commitments as a parent with my work and professional life. Again, I have Gibbons to thank, partly, for that. He never insisted on my staying home, and he never put pressure on me to conform.

Mwaikambo says that her husband supported her when, in 1987, she founded and became the first president of the Medical Women Association of Tanzania, which continues to contribute to strengthening skills in Tanzania’s health sector, with particular focus on female professionals.

“In fact, he supported every step I took in building my career. In 1994, he backed my decision to take a one-year sabbatical at the Harvard Medical School in Boston, sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation. On the fourth of September in that year, at night, the Toyota Land Cruiser he was driving in Dar es Salaam was involved in an accident, and he was flung out and killed instantly. One moment he’d been fine, going about his life, and the next he was gone forever. It was 27 years ago, but still it hurts,” she says.

Mwaikambo found “the admin that follows death” to be crushing.

“One of the worst aspects of losing Gibbons was the treatment I subsequently received from the community, being told that I’d caused his death because I worked too much, and that sort of thing. His family was against me administering his estate, and I had to fight them in the courts.”

Work and life

To cope with her grief, Mwaikambo threw herself into work, “into what had always sustained me”. She applied for promotions and ultimately became a professor. In 1998, she retired from the University of Dar es Salaam, which had been her employer for 30 years, and took a post as a paediatrician in the then Mission Mikocheni Hospital (it later became the teaching hospital for Hubert Kairuki University). A year later, she applied for and was appointed to the role of university vice chancellor, a position she held until 2006.

Mwaikambo continued to practise medicine until 2022, working through the COVID-19 pandemic in Kairuki hospital, a frontline made particularly dangerous and tragic by the denialism of Tanzania’s most powerful leaders.

“The coronavirus response in Tanzania was absolutely mismanaged. No meaningful lockdowns, no mask wearing and plenty of fiddling over vaccines, while we saw people dying in their masses, including friends and relatives,” Mwaikambo says.

In the wake of the pandemic, and her own retirement in 2022, Mwaikambo has been reflecting on the changes in healthcare she has seen in her lifetime.

“There has been undeniable progress, but not nearly enough,” she says.

“When I began work in 1970, infant mortality was 190 per 1 000 live births; today it’s around 35 per 1 000. We’ve seen a lowering of deaths from certain diseases as a result of routine vaccination, but suspicion of vaccinations remains deep-seated here in Tanzania. The pandemic exposed this, with many Tanzanians resorting to the use of local concoctions rather than opting for the vaccine, when it became available.

Around nine tenths of the population are still said to believe in witchcraft, and in every part of the country you find self-proclaimed witches charging fees to remove diseases such as diabetes. Many people still believe that bloodshot eyes signify possession, and so the very common medical problem of cataracts, often caused by smoke from cooking, also often goes untreated. The need for healthcare education is as pressing today as it was when I started practising,” she says.

Care for all

Mwaikambo is perturbed by the cost-sharing policy that has been in place since 1993.

“I was trained in a socialist country in which healthcare was free, and have never been able to reconcile myself with user charges that literally keeps many people from accessing care that would prevent death. I will be a proponent of universal health care until my last breath,” she says.

There are many more women in professions in Tanzania today, but Mwaikambo says she remains preoccupied with barriers to girls’ education.

“If the pandemic showed us anything, it is that we need hundreds of thousands of people trained in medical matters, and yet, as a female doctor, I’ve had to fight so hard to make my voice heard. In this country many people are still so wedded to the idea of the status quo that they’d rather die than be treated by a woman,” she says, adding that less than a third of girls finish their high school education, “and among the poorest communities this falls to just 6%”.

“When I was growing up there was a total gender gap when it came to all things STEM [science, technology, engineering and maths] and that gap remains huge. What is needed is early encouragement, role models visiting primary schools, women to advise and nurture the next generation.”

Tanzania’s first female doctor has spent much of her life being this example, sharing her story with young women — and she doesn’t intend to stop now.

“Thank your critics, I tell them, do it with a smile even, knowing that you will not be deterred. And when you reach the top, you will inspire others to do the same.”

The storm is not abating, and a flustered event organiser is handing out umbrellas, so that delegates can return to their rooms.

“I think your vehicle will do, for us older ones,” she says, and holds his gaze until the organiser stammers, “Well of course, of course, let me do that right away,” before running out into the drenching rain.

Sean Christie is a freelance journalist and author.