Terminally ill patients in the province have little access to pain relief, or basic care. Here’s one man’s story.

Roxanne Premchund would sometimes hear her father scream.

His cries were muffled by the loud gospel music coming from his room. But not enough to mask his desperate pleas.

Underneath the rhythmic melodies of praise, Premchund could hear her pastor-father imploring his maker.

“Why, God, why?” he would weep. “What have I done to deserve this?”

Pastor Lawrence Naidoo had moved into the spare room of his daughter’s Roodepoort home in Johannesburg shortly before being treated for cancer at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital.

She explains: “My dad was a devoted Christian. He would never take God’s name in vain. But he cursed God then and he cursed himself.

That’s when I knew how much pain he was in.”

Naidoo was diagnosed with stage two rectal cancer at Durban’s King Edward Hospital late in 2014 – there are four stages.

His chances of survival for the first five years after his diagnosis were about 90%, according to a 2016 study published in A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. But with the care Naidoo received, or its lack, he was soon to become collateral damage in KwaZulu-Natal’s failing health system – like many before him.

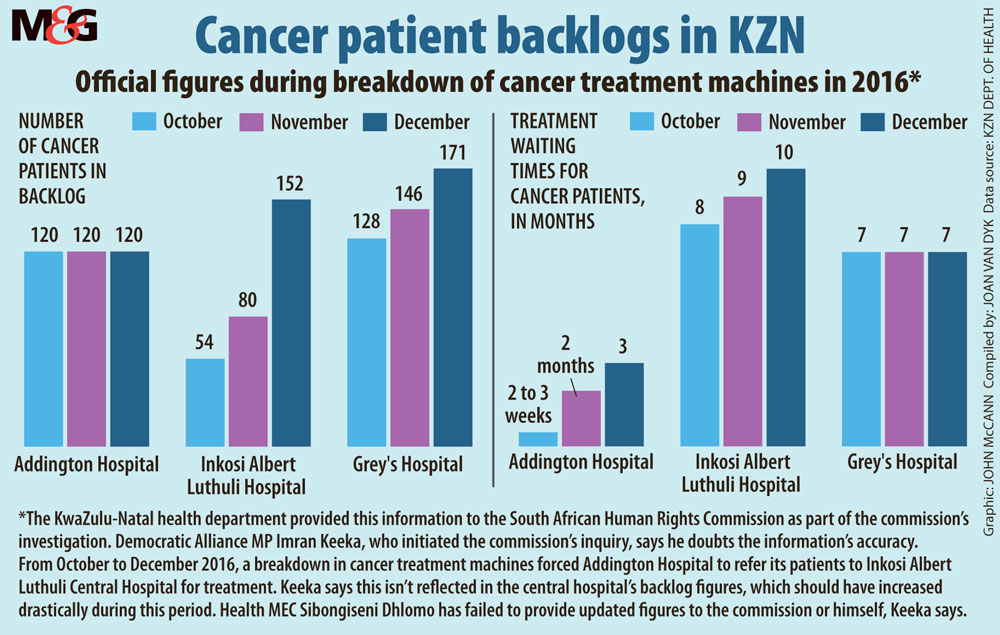

By the time the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) started investigating the state of cancer services in KwaZulu-Natal in 2016, the province had only eight cancer specialists working in the public sector.

That situation has since worsened.

By the beginning of February, KwaZulu-Natal had only two oncologists working in public hospitals and three cancer machines to treat a population of more than 10-million people, according to a statement by the province’s health department.

National Cancer Registry data show that in South Africa about one in eight people will suffer from some form of cancer during their lifetime.

In KwaZulu-Natal’s case, that translates to about 1.3-million.

Public sector patients in the province wait an average of five months to see a cancer specialist and a further eight months for treatment, a 2016 SAHRC report found.

After 13 months of waiting, it’s often too late to be saved. Some patients die. Others, like Naidoo, would have to learn that their cancer had become much more advanced and far more complicated to treat.

By the time doctors at Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital decided on a treatment plan for him, Naidoo’s cancer had progressed to stage three.

This had reduced his chances of survival to between 58% and 65%, the study published in A Cancer Journal for Clinicians study revealed.

When his family heard he would have to wait another seven months to start chemotherapy, they set out for Gauteng in search of better odds.

Premchund returns from the bathroom clutching a bunch of crumpled tissues.

“My brother phoned me immediately after it happened. Everything just fell apart,” she says, drying her eyes.

After completing 20 sessions of radiotherapy, oncologists at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital sent Naidoo back to Durban to rest for a month before his treatment could continue.

But before long, he was back in King Edward Hospital with no treatment options or hope of boarding a flight back to the City of Gold.

Realising these were his final days, Naidoo’s family wanted to take him home. But doctors warned he would not be admitted again if they discharged him against the hospital staff’s recommendations. “There was no medication, no radiation,” Premchund explains.

“Nothing to help him with that pain. He just ended up lying there … dying.”

Cancer can be extremely painful: as malignant tumours grow, they can tear through nerves, organs and even bone.

Almost half of people who died as a result of injury, disease or illnesses in 2015 were in pain, a 2017 report by The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief shows.

The first-of-its-kind study found few countries invest in dignified deaths for citizens. Almost 48 tonnes of pain medication such as morphine never made it into the hands of suffering patients in 2015.

Morphine is used to relieve severe pain and is especially important for treating patients with cancer pain. It is one of the most widely used pain medicines.

“Morphine is cheap and safe to use. It is the ideal pain relief medicine for the underserved developing world.

A month’s supply for a patient can cost less than a loaf of bread,” study co-author Liz Gwyther says. Gwyther is the chief executive of the Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa and chair of the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance.

Most of the patients in the study were living with cancer or HIV. More than 80% of those who had no access to painkillers were from low-income countries.

South Africa is the only African country that prescribes more than the global average of morphine each year, according to 2015 data from the Pain Policy Studies Group at the University of Wisconsin. Yet many patients die in agony because they still go without it.

“Morphine is relatively cheap in South Africa, but the country’s health workers aren’t properly trained to manage pain,” Gwyther explains.

South Africa’s “pain gap” can be bridged by expanding nurses’ role in prescribing and monitoring highlevel pain medication like morphine,

Gwyther argues. “Especially in rural areas where doctors are scarce.”

But under the Nursing Act nurses in South Africa cannot legally prescribe strong pain medications such as morphine.

The South African Nursing Council is looking at amending the Act. But even then, it might not translate into actual help for people like Naidoo, given the severe staff shortages in the public sector.

“My dad died without food, without water. Filthy,” Premchund explains. “Where were the nurses, where were the doctors that were supposed to be checking up on him?”

[WATCH] Why cancer services in KwaZulu-Natal have all but ground to a halt

Palliative care improves the quality of life of people with threatening illnesses such as cancer. A major component of this type of care is managing pain but it also includes psychological and even spiritual counselling for patients and their families – to help them die in a humane way.

Gwyther explains: “Palliative care goes one step further than treatment. We make sure a patient’s mind, body and spirit are looked after.”

However, palliative care is not only for patients nearing the end of their lives. Ideally, care should begin as soon as a patient is diagnosed, says Julia Ambler, director of the nonprofit Palliative Treatment for Children (Patch).

She says palliative care should be seen as supportive care rather than only end-of-life care: “Some doctors will say their patient is not ready for palliative care because they’re not dying yet. But many patients will be cured and still need help managing their symptoms.”

A new policy on palliative care could turn the tide against chronic pain in the country. The policy was approved by the National Health Council in 2017. Under the new policy, community based palliative care teams will treat bed-bound patients in their homes.

The strategy includes plans to train nurses to prescribe morphine in a bid to cater for the country’s rural hospitals.

KwaZulu-Natal began piloting the new plan last year when the provincial health department started to pay hospices about R60000 monthly to expand services and to train public health workers.

But without oncologists and equipment to provide a diagnosis, patients in KwaZulu-Natal stand little chance of a comfortable death. The lack of specialists and treatment machines in KwaZulu-Natal is fuelling the need for palliative care, says Gwyther. She argues patients who could be saved are being diagnosed too late. “Palliative care should never be used instead of treatment – the two should go hand in hand.”

The KwaZulu-Natal health department has increased its efforts to detect cancers early in a bid to take some of the pressure off short-staffed hospitals. But the dearth of specialists in the province may become a chronic condition in itself.

With no qualified oncologists left in KwaZulu-Natal, the province can no longer train new cancer specialists, says Health Professions Council of South Africa spokesperson Priscilla Sekhonyana.

The province’s three oncologists-in-training will be completing their studies in the Western Cape health department, according to a KwaZulu-Natal health department statement.

KwaZulu-Natal’s health department has been forced to ask for help outside the province. In February, the department awarded the Wits Health Consortium a tender to provide oncology services at Addington Hospital and Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital for five days a week, says University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) communications officer Deborah Minors.

But the contract is only valid until the end of July. Even patients who have a prescription for morphine may have problems as the drug is often out of stock at pharmacies.

Gwyther argues that previous shortages may be behind the stock-outs. “The government estimates how much medication the country needs by looking at the use from previous years. This can cause a vicious cycle of shortages.”

Although the new policy will not be an immediate fix for suffering patients in the province, palliative care training will soon be mandatory and standardised for all medical students, says Charmaine Blanchard, senior lecturer at Wits’ Palliative Care Centre.

Increasing palliative skills and services isn’t just humane, it’s also a way to save money.

Patients with access to palliative care are less likely to need expensive emergency care, the 2017 Lancet study showed. And, emergency spending on healthcare pushes more than 100-million people into poverty each year, another study, published in Health Systems and Policy Research in 2015, found.

Early access to palliative care can also significantly improve a patient’s quality of life. A 2015 New England Journal of Medicine study of patients with advanced lung cancer found that those who received palliative care as soon as they were diagnosed lived about two months longer than those who did not and were less likely to suffer from depression.

But, Gwyther points out, ultimately, everyone, no matter their prognosis, has the right to die with dignity. “Doctors and nurses are more focused on curing diseases than caring for the people experiencing it. These patients often feel they’re just a number and they are not being taken care of.”

Back in Roodepoort, Premchund scrolls to a photograph of an emaciated Naidoo on her tablet. His head rests on a faded floral pillow that her mother brought him from home. The muted colours are a stark contrast to the clinical greys and blues around him. “My mom sent me this photo after his death,” she says softly.

When the Naidoos had their father and husband admitted to Charlotte Maxeke, he was hopeful. “He was getting treatment and pain medication. And he was a new person. He wanted to live,” Premchund says.

But everything changed during his second stay in King Edward Hospital. “I’ve had to watch my dad suffer,” she says, glancing at a picture of the reverend above her dining room table. “There were no services, no pain medication, nothing to give him any dignity.

“I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.