- Treasury allocated R15-million until 2023 to roll out South Africa’s first gender-based violence and femicide action plan. Trouble is, gender-based violence and femicide costs the country between R20-billion and R40-billion each year.

- More than a year after the action plan was released, the council that will oversee its implementation has not yet been appointed.

- This is the story of two mothers mourning their children, who are now among those lost to the country’s femicide epidemic.

Inside Roots Butchery in the town of Acornhoek in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, a butcher in red overalls guides a slab of beef through a meat saw. The blade screeches as it cuts through bone.

Around him, other workers are preparing packages for Saturday morning shoppers queuing in the cool, fluorescent-lit shop, a welcome break from the October lowveld heat. To the left, a curtain of raw sausage hangs from stainless steel rails.

There’s a normality to the scene that belies the trauma of recent events.

One Monday in September, Roots employees say two of their colleagues didn’t report for work.

One was Gloria Sekome – a cashier who’d recently transferred to a branch in nearby Hazyview. The other was her former partner Danboy Nkuna, who worked 10km away, at the Roots outlet near Mahushu.

After six strained years together, Sekome had recently ended her relationship with Nkuna.

Three days before Sekome’s co-workers noticed her absence, Clacy Sekome had received a panicked call from her daughter as she returned home from the butchery. She sounded terrified, Clacy recalls.

“They’re blocking my way,” Sekome had whispered, but the call cut out before she could finish her sentence. When Clacy phoned back, Sekome’s cell phone was switched off.

The next day, Clacy tried to report the situation to the local police station, but was sent from pillar to post. Having had no success at two precincts, she finally arrived at the Bushbuckridge police station, where Sekome had opened a protection order against Nkuna in 2018. There, she waited for four hours before she was helped.

At 11am the next day, Clacy received a call from the police, asking her to join them at the state mortuary. “I found my child lying there with her throat cut,” she says, her voice breaking.

’None of us are okay’

Seven months on, Danboy Nkuna admitted to Gloria’s murder and is waiting for his day in court.

But Sekome’s was not the only death in Bushbuckridge that week in September; she was one of three women murdered by their intimate partners, according to local media reports.

In a fourth, similar event, Rachel Mashego’s ex-partner tried to strangle her. When she escaped, he poured petrol on the floor of the room in which their children were sleeping, and lit a match. The man had, in Mashego’s telling, been threatening violence for years. He’d say: “I want to see a corpse come from this yard,” she says.

Mashego’s eyes are cloudy as she describes sprinting away with Tokelo, 5, in her arms – and still on fire. “I ran with him. He [the boy’s father] was chasing us with a stick.”

Tokelo died in hospital shortly after.

Mashego’s former partner was arrested, but released on R500 bail the next day.

“We have not been okay [since that night],” she says from inside the scorched room. “None of us are okay.”

In this part of the world, stories of violence are everywhere

Akimo Mabuso shuffles in a plastic chair in a tiny church hall near the municipal building where he works. He’s a social worker at the government-funded Vuwiselo victim empowerment programme in Acornhoek.

On this side of the world, stories like those of Mashego and Sekome are everywhere, Mabuso says; his workdays are filled with harrowing tales. “Acornhoek is full of gender-based violence [GBV].”

He believes that tide is rising – a result of fallout from the COVID pandemic, the ensuing lockdowns and declining employment (unemployment in Bushbuckridge is at 45%-50%, according to the municipality’s 2019 development plan – far higher than both the provincial and national rate).

Police statistics would seem to confirm the trend.

Between 2015 and 2019, the number of reported murders in Bushbuckridge rose steadily from 21 to 32, according to police data collated by the data journalism centre Media Hack and Bhekisisa – an increase of about 30%. (In 2020, the number returned to 2015 levels.)

Over the same period, reported rapes increased by approximately 4% from 91 to 95.

While it’s not possible to compare Bushbuckridge’s statistics with those of other police stations – the police service doesn’t provide enough data to do so – the National Shelter Movement has noted a steady increase in gender-based violence in Mpumalanga more broadly, says provincial representative Fisani Mahlangu.

“We need support,” she urges.

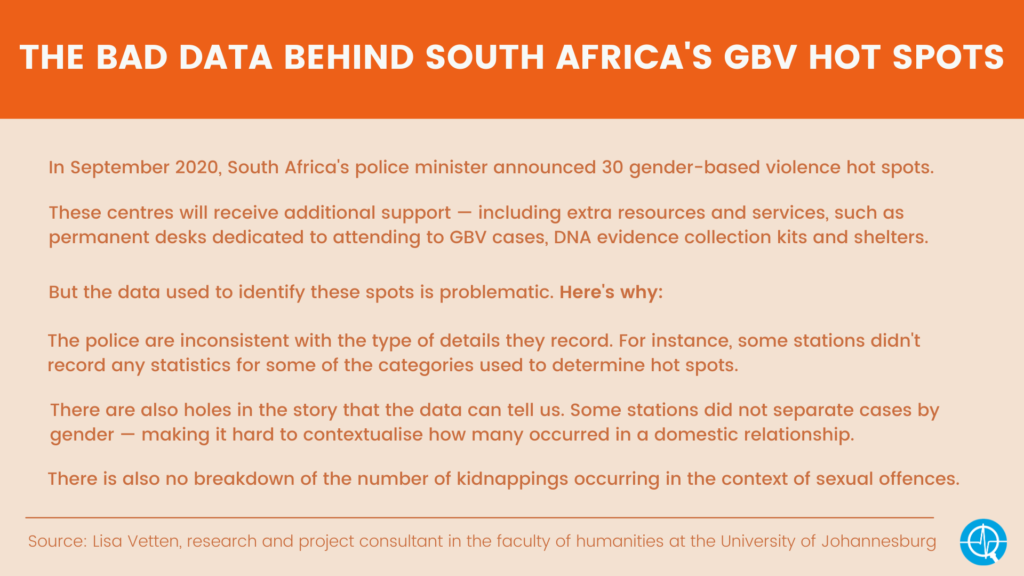

But additional help may be a way off. When Police Minister Bheki Cele announced the country’s 30 gender-based violence hot spots in September 2020, not one town in Bushbuckridge was on the list. Neither was a single district in Mpumalanga.

Limpopo and the Northern Cape were also not included. Instead, the list was comprised mostly of urban towns and settlements such as Diepsloot and Alexandra in Johannesburg, Khayelitsha, Gugulethu and Mitchell’s Plain in Cape Town, Mthatha (Eastern Cape) and Umlazi (KwaZulu-Natal).

Having been flagged, the 30 centres will each receive additional support — “extra resources and services, such as permanent desks dedicated to attending to GBV cases, DNA evidence collection kits and shelters”, GBV expert Lisa Vetten wrote for Bhekisisa in November. They’ll also benefit from “awareness campaigns and strategies … to raise awareness of gendered forms of violence and abuse”.

Mabuso and his Bushbuckridge colleagues, however, won’t have access to any of this largesse.

Why the government’s GBV hot spots could be based on bad data

Vetten considers the data that is used to identify GBV hot spots problematic. For a start, she says, the police are inconsistent with the type of details they record. The crime stats used to calculate the hot spots are for rape; kidnapping with the purpose of committing a sexual offence; trafficking, especially for purposes of sexual exploitation; murder and attempted murder within the context of domestic violence; and assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm.

But in 2019/2020, for instance, the police provided no statistics on trafficking. “They also didn’t disaggregate the statistics of their top 30 stations lists — for murder, attempted murder and assault with the intent to cause grievous bodily harm — by gender,” explains Vetten.

“So it’s not possible to speculate on how many of these crimes occurred within the context of a domestic relationship. There is also no breakdown of the number of kidnappings occurring in the context of sexual offences.”

It’s not only messy data that raises questions about how the hot spots were identified; the police have also failed to control for population size. Because police stations are ranked according to the total number of cases reported, those serving more densely populated areas feature more prominently, Vetten says.

“Not having adjusted station figures for population size may help explain why 24 of the 30 hot spots are found in the three most populous provinces, and none [are] in the least populated province.”

Identifying where women are at particular risk of GBV and taking action can make a tremendous contribution, Vetten explains. “But you need to be sure you’ve pinpointed the right spots.”

The police service, however, stands by its figures, which were verified by Stats SA, says department spokesperson Lirandzu Themba.

And the hot-spot list is not based on crime statistics alone, she says. In identifying the locales, the police also took into consideration information and research from government departments such as social development, and justice and constitutional development.

Back in Acornhoek, however, no social worker contacted the Sekome family after Gloria’s murder.

Gender-based violence still haunts the family. Gloria’s two children, who now live with Clacy, were set to receive counselling from a psychologist at a nearby public hospital.

But by the time their first session came around, the violent epidemic had struck again.

“The psychologist was killed by her husband.”

What counts as femicide?

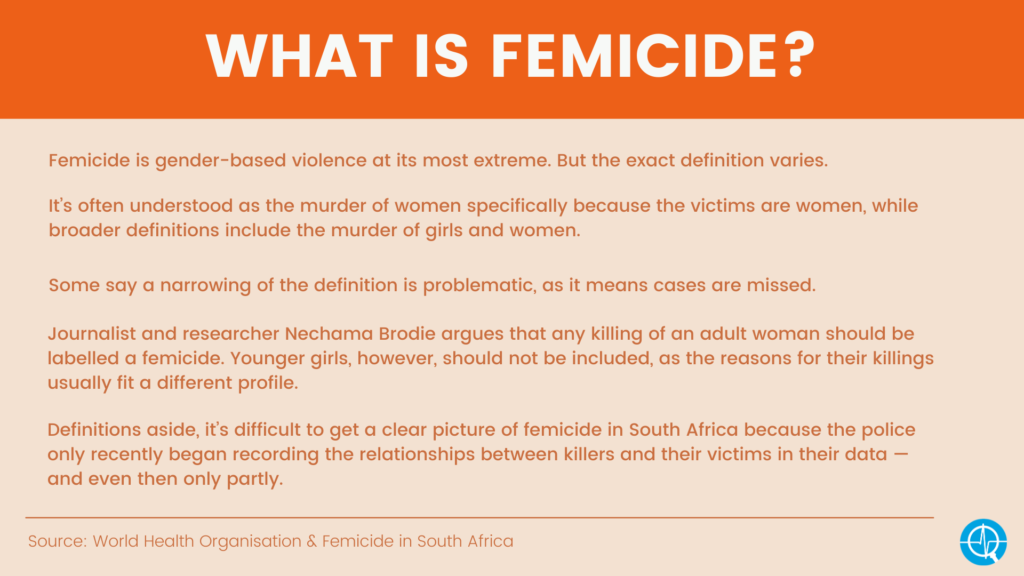

But Gloria Sekome’s story is one of femicide – GBV at its most extreme. More narrowly, her murder would count as “intimate femicide”, in World Health Organisation (WHO) terms, as it was perpetrated by a former partner.

Definitions of femicide, however, vary. It’s often understood as the murder of women specifically because the victims are women, while broader definitions include the murder of girls and women, the WHO notes.

Some say a narrowing of the definition is problematic, as it means cases are missed.

In her 2020 book Femicide in South Africa, for example, journalist and researcher Nechama Brodie argues that one cannot separate the patriarchal societal norms that lead to the killing of women from the motives behind their murder. For this reason, she reasons, any killing of an adult woman should be labelled a femicide. Younger girls should not be included, as the reasons for their killings usually fit a different profile, Brodie writes.

Definitions aside, it’s difficult to get a clear picture of femicide in South Africa because the police only recently began recording the relationships between killers and their victims in their data – and then only partly.

In 2019, the police could identify the relationship between the perpetrator and their victim in just one-fifth of all murders in SA; 16% of those were attributed to a boyfriend or husband. Between April and June 2020, 55% of murders related to GBV were perpetrated by husbands or boyfriends, according to the police.

Poverty is a key contributor to intimate partner violence, studies have shown, though the link between the two is complex. For men, not being able to provide economically is linked to perpetration of intimate partner violence, according to 2018 research published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One. The study authors analysed data from more than 1 000 men and women living in informal settlements in SA.

For women, on the other hand, the link between poverty and food insecurity makes them more susceptible to this kind of violence. There’s a higher chance for violence between partners when there’s conflict about a lack of food and money. It’s also harder for women to leave an abusive relationship when they rely on their partner’s income to survive.

Childhood trauma, substance abuse and poor mental health have also been linked to intimate partner violence.

Back in Acornhoek, Mabuso’s voice echoes in the empty church. The number of femicides in Bushbuckridge is “not normal”, he says. “We need an intervention.”

Research shows violence drops when men believe women are “human beings, like us”

In an attempt to prevent the kind of violence that led to Sekome’s death, Mabuso’s organisation spreads awareness about the dangers of harmful gender stereotypes at taxi ranks in Bushbuckridge. It’s part of the department of social development’s “Men Championing Change” programme, launched in 2018, which works with men to help change the social practices that drive intimate partner violence and HIV infection.

The organisation also helps victims get back on their feet. But it’s not enough, Mabuso says; there needs to be support for perpetrators too.

Back in 2012, the nonprofit, Sonke Gender Justice, ran the “One Man Can” project in the area as part of a three-year study. As part of the programme, trained community mobilisers ran five two-day workshops over a two-year period. These aimed to get people to think differently about gender, violence, alcohol use and sexual behaviour.

But researchers who evaluated the impact of the project found mixed results, according to a study published in Culture, Health and Sexuality in 2020.

They showed that the best way to prevent violence was to get men to recognise women and children as “human beings, like us”. While men, however, began to show more equitable attitudes about gender as the programme progressed, women didn’t.

Ultimately, the researchers found no statistically significant decrease in intimate partner violence. And where there was a decrease in violent behaviour, participants struggled to sustain it.

“Workshops and community activities can be important contributors to reducing violence,” the authors wrote, “but [they] may not be enough to sustain the change for people with a history of violence.”

Is it possible to prevent violence against women and girls?

For mourning mothers such as Mashego and Sekome small changes in violent men’s attitudes do little to erase the images of their children’s damaged bodies.

Since Sekome’s death, Clacy has become more vigilant about the whereabouts of her three remaining daughters. “I have this fear for them,” she says. “If men are these monsters … [what] boyfriend will they find?”

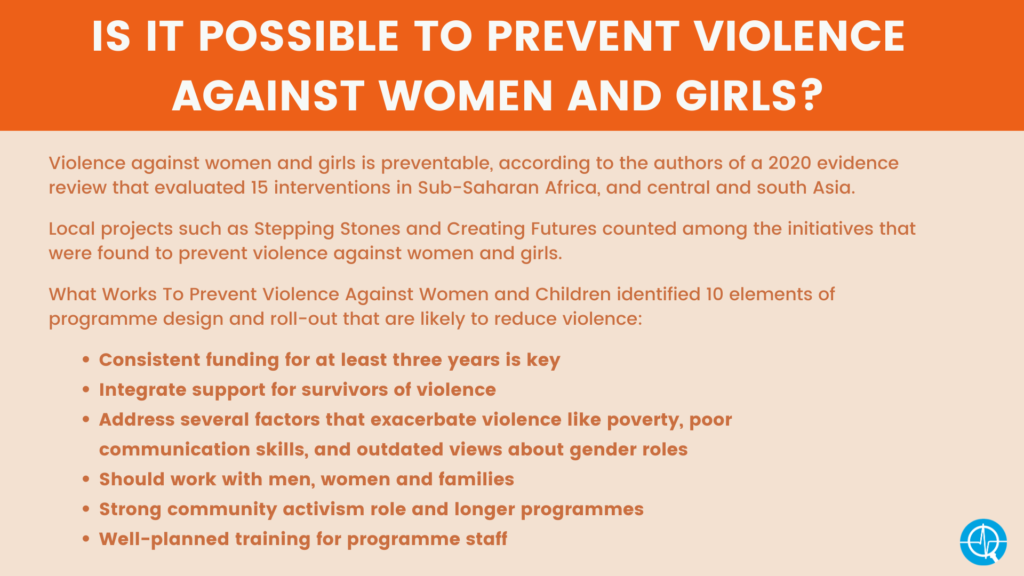

But violence against women and girls is preventable, according to the authors of a 2020 evidence review for What Works To Prevent Violence Against Women and Children, a global research nonprofit.

The project evaluated 15 interventions to curb intimate-partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa, and central and south Asia. Local projects such as Stepping Stones and Creating Futures counted among the initiatives that were found to prevent violence against women and girls.

After reviewing the trials and triumphs of projects in developing countries, What Works identified 10 elements of programme design and roll-out that are likely to reduce violence. For example, consistent funding for at least three years is key, as is well-planned training for programme staff.

It’s this kind of evidence that informed SA’s first national strategic plan (NSP) on gender-based violence and femicide, published in March 2020, says SA Medical Research Council researcher Nwabisa Shai.

The 132-page document is supposed to build the co-ordinated response South Africa needs to stop violence against women and children. It outlines six pillars of intervention: accountability, prevention, safety and protection, support, economic upliftment and information systems.

The NSP has bold five-year goals, including amending 12 pieces of legislation and creating a national database of GBV and femicide that will rely, in part, on disaggregating murder statistics from the police to find out specifics about the relationship between victims and perpetrators.

It’s likely that implementation will be left to nonprofits and civil society, Shai says, making the NSP a “tool to make sure everybody involved is singing from the same hymnbook”.

This will not only make peer-reviewed and research interventions more accessible to implementing organisations and departments, but will also begin documenting the work of community projects that may have been making an impact for years, Shai says.

“The challenge we must overcome is the belief that prevention is optional.”

Red tape stalls South Africa’s first gender-based violence action plan

It seems, however, that the roll-out of the NSP has been hamstrung by the government’s own bureaucratic processes.

The interim steering committee that drafted the document delivered the NSP on time in October 2019, but it was only approved in March 2020, missing the deadline to get funding from National Treasury, says committee secretary Sibongile Mthembu.

And, as the committee’s mandate lapsed in March last year, responsibility had to be handed to the department of women, youth and persons with disabilities. That’s apparently left many in civil society unsure of who is in charge of what.

Part of the confusion is that the council meant to oversee the NSP roll-out has not been established, due to disagreements about how the body should be set up, as well as delays caused by the COVID lockdown, explains Mthembu.

In the absence of a council, the department apparently asked stakeholders to assist in setting achievable goals for the first 100 days of the NSP which started in March 2020. (The department did not respond to Bhekisisa’s requests for comment.)

But even then, implementation was slow.

With the plan not yet funded, many activists and organisations volunteered to keep the process ticking along, Mthembu says. But when organisations asked the government for help, by paying for data, for example, department officials argued that such organisations are already subsidised by the state.

An online repository that tracked weekly progress for the 100 days reveals mixed results from the six teams (one for each pillar of the NSP).

“No one really knows what the NSP implementation actually looks like and the loose process can at times lead to dead ends and frustration,” one team said.

In Mthembu’s team, efforts to start creating a national database on GBV went nowhere because of the voluntary nature of the work.

“That’s where we’re failing again,” she says, “expecting women to volunteer their time.”

Additional resources may ameliorate the problem. According to the 2021 Budget Review, the department of women is set to receive R15m over the next three years to establish the council and roll out the NSP. It seems a small price to pay, given that consulting firm KPMG in 2017 estimated that gender-based violence cost South Africa between R20-billion and R40billion a year, or 1% of GDP.

Everyday reminders in the soap and in the soil

Back in Acornhoek, the morepho growing in Clacy’s yard are ready for harvest, but she can’t bear the thought of crossing the yard to dig up the vegetables. She knows memories of her daughter will overwhelm her as soon as she lifts the first handful of soil – mashed morepho with salt was Sekome’s favourite meal.

If not in the morepho, Clacy says she’ll find her daughter in the soapy water when she washes the family’s clothes.

“I can’t sleep,” she says, fumbling with a disintegrating tissue. “This will haunt me until I die.”

This story was supported by the Sylvester Stein fellowship awarded to Bhekisisa by the Canon Collins Educational and Legal Assistance Trust.

Joan van Dyk was a health journalist, senior health journalist and news editor at Bhekisisa between 2017 and 2023.