- South Africa’s medicines regulator, Sahpra, approved the new HIV prevention jab, CAB-LA, on 2 December.

- The shot is taken every two months and virtually wipes out someone’s chances of contracting HIV through sex.

- The health department says, it could start rolling out the jab on a large scale within nine months — but that depends on the price the drugmaker will sell it at.

- We travelled to Crossroads near Cape Town to speak to young women in a CAB-LA trial who have been using the injection for the past six months.

About a five-minute drive off the Borcherds Quarry Road offramp to Crossroads near Cape Town on the N2 highway, behind an amagwinya (vetkoek) shop and a tin shack, a cream, two-storey building with a bright rainbow sign towers out.

It has heavy security — four security guards with orange reflective vests are guarding the outside of the premises. Past the entrance gate, CCTV cameras and more guards watch over the Emavundleni Prevention Research Centre, where Amanda Roberts, 23, is scrolling on her phone, waiting on a doctor in a consulting room.

It’s pouring outside and the streets are muddy, but this hasn’t deterred Roberts, a teaching assistant, from coming to get a two-monthly jab, called CAB-LA. The shot, which will be injected into her buttocks, is lifesaving because it virtually eliminates the possibility of her contracting HIV through sex.

In 2016, Roberts’s mom died of HIV. Her mother’s surviving twin sister has now contracted the virus too. “I’m afraid of getting infected and don’t want to go down the same road as them,” she says. “I’ve been left with my little brother and now have to take care of him alone.”

Roberts has long, dark-red braids draping down her back and a golden nose ring and is outspoken.

“I’m not ashamed of coming to the clinic,” she says. “Everyone knows I’m getting this shot.”

A few years ago, Roberts and her boyfriend broke up for four months.

She explains: “During that time he must have slept with someone else, because shortly after we got back together, I contracted a sexually transmitted infection and he was the only person I had sex with.”

She checks a WhatsApp message, pauses, and says: “I thought to myself, what if he had slept with someone who was HIV positive?”

“I was desperate to take this injection”

The Emavundleni Prevention Research Centre, which is run by the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre at the University of Cape Town, is a world-class clinical trial site. Part of the open-label phase of a study called HPTN 084, is unfolding here. In an open-label study both the researchers and trial participants know which drug volunteers get.

In this study, Roberts and more than 3 200 other women from sub-Saharan Africa get CAB-LA. Researchers are looking at how easy or difficult it is to roll out the medication because scientists have already established that it works extremely well to prevent HIV infection.

[WATCH] Find out what women who have used CAB-LA think of it

This information can help the government to know what resources they will need or what obstacles they can expect along the way, when (and if) it eventually rolls out the injection to hundreds of thousands of people.

The country’s medicines regulator, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (Sahpra) registered the jab on 2 December. The health department now has to decide if it will buy it and how much it is prepared to pay.

Roberts has been taking CAB-LA for six months; today’s jab is her third.

She says: “I was desperate to take this injection. I knew I needed it.”

The less often you take the pill, the less effective it is

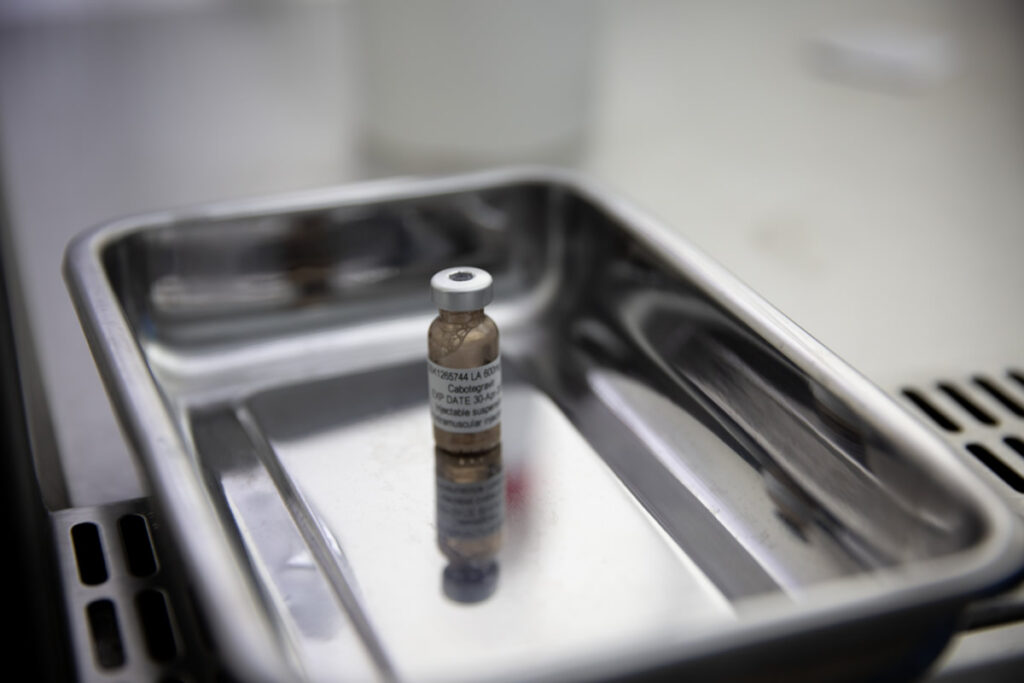

CAB-LA stands for long-acting (LA) cabotegravir — cabotegravir is an antiretroviral drug (ARV) that some HIV-infected people use, together with other ARVs, to keep the virus in their bodies from making copies of itself. When such medicine is used to prevent HIV infection — that is, if it’s taken before exposure to HIV — it’s called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP.

“It works a little bit like a contraceptive injection, which prevents you from getting pregnant,” says Linda-Gail Bekker, the head of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre and one of the lead investigators of the South African part of the HPTN 084 trial. “The injected drug [cabotegravir] goes into the muscle and sits there for two months, from where it slowly dissolves into the bloodstream. And then it works its magic by preventing HIV from entering your cells.”

Before Roberts took CAB-LA, she used a daily HIV prevention pill that consists of two ARVs, tenofovir and emtricitabine, for five years — but it was difficult to remember to swallow it each day.

[WATCH] PrEParing to protect yourself: What young people need to know about this free HIV prevention pill

She explains: “I had to take the pill at the same time every day for it to work [best], but this wasn’t possible over weekends when I went to parties. I didn’t want to carry my medication with me, because people would think I’m sick when they saw me take it, and spread rumours that I’m HIV positive.

“That’s when the problem started with me skipping some of the days.”

The less often Roberts took the pill, which could reduce her chances of getting infected with HIV by more than 90%, the less effective it was.

“That’s why I’m relieved that I now only have to come to the clinic once every eight weeks,” she says. “I feel safer and can relax.”

The jab works better than a daily pill

Roberts isn’t the only person for whom CAB-LA works better than a daily pill. Studies have found that the jab works 66% better in men who have sex with men and transgender women and is 88% more effective at preventing HIV infection in young women than oral PrEP. Researchers think it’s likely because the injection is so much easier to take, because you only need it once every two months.

A modelling study published in The Lancet HIV this month revealed that, compared to the daily pill, CAB-LA can reduce HIV infections and Aids deaths by more than three times. In actual numbers, this translates to CAB-LA preventing between 35 600 and 52 000 new infections a year compared to the pill’s 9 000 to 16 800.

These cuts are substantial. South Africa currently has 200 000 new HIV infections per year — 130 000 of them among young women such as Roberts. So CAB-LA can potentially lower new infections by 15-28% over the next 20 years (the timeframe The Lancet HIV study looked at) compared to the daily pills at 4-8%.

[LISTEN] Why SA needs the anti-HIV injection — for R120 a pop

By 2025, South Africa wants to more than halve yearly new infections to 74 000 or fewer, but that will be through many methods, not just CAB-LA. This could include, for instance, increasing the number of HIV-positive people on treatment (when people with HIV use ARVs correctly, the amount of virus in their bodies becomes so little that it becomes scientifically impossible for them to transmit HIV to their sexual partners); getting people to take oral PrEP; making available a vaginal ring, which women can insert to help prevent infection and that the health department will soon start to procure; promoting condom use and advocating for delayed sexual debut among teens.

By the end of September, 726 745 people in the country had started the pill at 3 162 public health facilities and partner sites, the latest health department figures show.

But the problem, around the world, is that the uptake of the pill has been much lower than expected — so much so that the United Nations’ goal to get three million people globally on the pill by 2020, was missed by two-thirds.

Moreover, many people who take the pill don’t use it consistently, and therefore don’t get the full benefit.

How much does CAB-LA cost?

CAB-LA has been available in the United States (US) for the past year.

But there’s a catch.

The jab, made by the drug company, ViiV Healthcare, is sold in the US at R54 000 a pop. According to The Lancet modelling study, that is 200 times more than what would be sensible for South Africa to pay.

Why?

The researchers calculated that for CAB-LA to be cost-effective for South Africa, the health department shouldn’t fork out more than double than what they pay for the daily HIV prevention pill. A month of pill supplies per patient costs the government R60 (this is only the cost of the pill and doesn’t include administrative fees such as health workers’ time, transport costs, etc.), so the public health sector shouldn’t pay more than R240 (twice the price of the pill) per two-monthly shot (the study says between $9.03 and $14.47 based on USD-ZAR exchange rates at the time of the research’s publication).

But ViiV Healthcare’s head of research and development, Kimberly Smith, told Bhekisisa it’s impossible to produce the jab at the same cost as a pill.

“CAB-LA is a sterile, injectable product with a very complex manufacturing process. The instances where it’s been compared to the manufacturing cost of a simple, white pill are just not realistic.”

Watch Health Beat to find out what ViiV healthcare says about CAB-LA

Cheaper, generic versions of CAB-LA will make the jab considerably more affordable. ViiV Healthcare already has an agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool, an international organisation that helps to get such non-brand products made, to grant licences to three generic drugmakers. But, once the licences have been awarded, it will take between three and five years for the manufacturers to prepare for production and have ready-made jabs to sell.

So what happens in the meantime?

To get around this, ViiV Healthcare has offered to market their branded product at a much reduced, “not-for-profit” price to 90 poorer countries until generic products are available. South Africa is included in this list of countries.

But the drugmaker hasn’t yet announced what this price would be, and the fee will depend on how many orders donors and governments can commit to, as production at scale will reduce costs.

The Lancet HIV study, as well as scientists and activists interviewed by Bhekisisa, report that the price that ViiV Healthcare is considering ranges between R4 080 ($240) and R4 590 ($270) per patient per year — far above what South Africa can afford.

At R60 per patient per month, the annual cost per patient per year of the daily pill comes to R720 (without administrative costs). If the suggested price ranges that ViiV Healthcare is considering are correct, they’re considerably higher than what researchers say would be cost effective for South Africa.

But Smith says: “There are a lot of prices floating around, and for the most part, they’re inaccurate, because they don’t fully take into account some of the complexities, such as volume, that will influence the cost.”

Will the health department buy CAB-LA?

After Sahpra’s registration on Friday, South Africa now joins other African countries such as Zimababwe, where the jab has been authorised for use as well.

The National Essential Medicines List Committee, NEMLC, a group of experts appointed by the health minister to advise him about medicines, will now start to update a technical review on CAB-LA that they published in May.

NEMLC’s initial review recommended that once Sahpra had registered CAB-LA, and the price at which ViiV Healthcare would sell the shot to poorer countries was known, a budgetary impact assessment would be done.

The health department’s director of affordable medicine, Khadija Jamaloodien, says the updating process and budget assessment may take between two and three months. NEMLC will then decide if it’s worth it for South Africa to roll CAB-LA out in the public sector and, if so, recommend a price.

Jamaloodien explains: “Sahpra looks at safety, efficacy and quality data of a product to establish if it’s safe to use and if it works the way a manufacturer says it does. NEMLC, on the other hand, compares the product to the current standard of care [in this case the daily HIV prevention pill] to determine if buying the product [in this case CAB-LA] makes economic sense.

“Just because CAB-LA works better than the daily HIV prevention pill, doesn’t mean that we necessarily need to pay double the price.”

A factor that will complicate the health department’s ability to negotiate a reasonable price with ViiV Healthcare is the fact that CAB-LA, once approved, will be the only product of its kind — a long-acting, injectable PrEP option — available in South Africa, so ViiV Healthcare will have no competition. “With a monopoly, negotiations become more challenging, because they hold us to ransom,” Jamaloodien explains. “But that doesn’t mean we can bluntly accept the price that ViiV Healthcare puts on the table.”

Jamaloodien says if Sahpra approves CAB-LA soon, and NEMLC recommends buying the jab, the health department will go out on tender — a process that will take about six months. That could mean that South Africa could potentially see the mass roll-out of the jab within nine months after Sahpra registration.

Will people use the jab?

That, however, doesn’t mean that people would necessarily line up for it.

“We need to learn from the mistakes we made with the roll-out of oral PrEP,” Bekker says. “In part, we’ve had a low uptake because we stigmatised the pill by initially rationing the commodity and only making it available only to high risk groups such as sex workers and men who have sex with men.

“This led to people in the larger society, who are also at risk of HIV infection, thinking that the pill wasn’t for them. We’re going to have to work hard at creating demand.”

Bekker says “more choice” is what may make the difference. “With contraception we know that the more options — the pill, injection, implants, IUDs [intrauterine devices] — we offer women, the more likely they are to use one of those methods and stick with it. Hopefully, choice in the case of HIV prevention, plays out in the same way.”

Mitchell Warren, who heads up the US-based advocacy organisation Avac concurs: “CAB-LA on its own will not end the HIV epidemic. But I can tell you that without it, in the absence of a vaccine, we will never end the pandemic.”

Additional reporting by Linda Pretorius.

[2 December 2022, 16:42: This story was updated to reflect the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority’s registration of CAB-LA on 2 December, which happened a day after the publication of this article.]